75 — March 2022

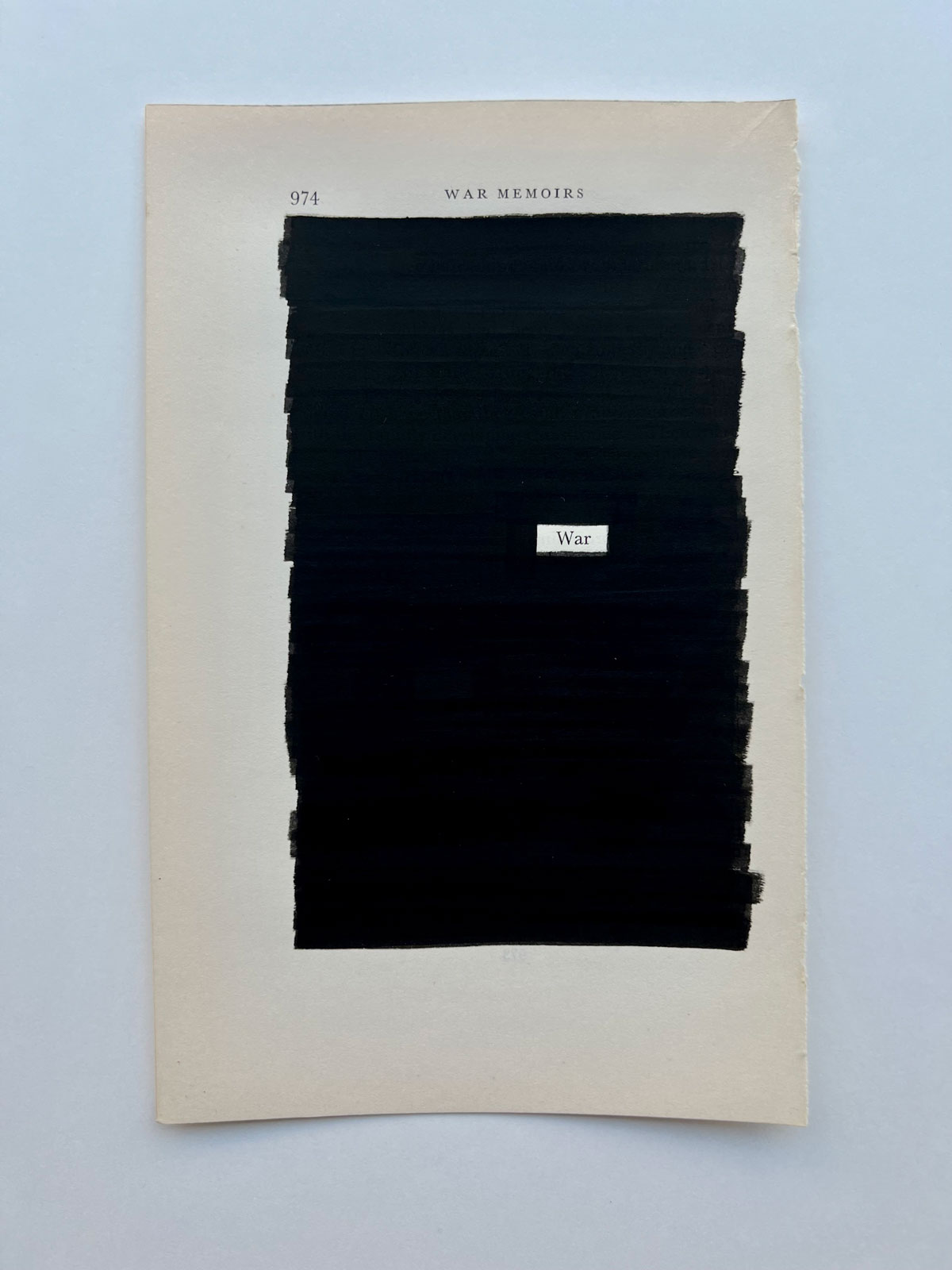

Memories Of War, 2016

Page from a book, felt pen, 22.2 × 13.3 cm.

Courtesy of the artist

Memories of War1

Anna Smolak

In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.

— Kazimir Malevich

Memories of War reached me by post. It’s uncanny how much can fit into the envelope. On the faded page of the book, the word ‘war’ stood out from the black splash. The manner in which he had painted over the remaining text revealed activity that was as systematic as it was compulsive. He used a felt tip – with its straight, overlapping lines making way for memory. At first, the gestures were freer; this you could tell from a different shade of the ink. Apparently, he did not carry the lines through to the edge and he had to correct them, starting again from their middle section. Halfway through the page, the black grew intense; I imagine that he must have gone over the line again and again. Perhaps he was in a stupor, mulling over something intensely in his head, the movement of his hand becoming automatic. Yet the precision with which he framed the three letters ‘WAR’ indicates deliberation.

In his country, like in a well-run theatre, the stage set is changed efficiently and silently. New, homogenous façades are brought in, solid frames are fitted into the empty eye-sockets of windows. Bomb craters fill up with flower beds. Everything is replaced, even the dates of the atrocities, and – after dark – the graves of the victims are swept out of sight, to the city’s periphery. Now, it is clean. Now, it is whole. The places of worship, the lavishly lit futuristic districts, the street coffee vendors, the wide roads. War? What war? Here, in the centre of the world, great care is taken to make sure that the war is forgotten.

Yet, I remember – the old, white car parked on a country road. Men, women and children kept getting into it, their clothes in tatters. It seemed liked a bottomless pit. Twenty of them managed to squeeze in, to escape from the city. And a gate, set in solid steel, with a wrought-iron frame. The richer the house owner, he told me, the bigger and grander the gate. Now, useless gates full of bullets holes are also being swapped for new ones. I remember someone’s household – entire worldly goods, stuffed into two huge wooden boxes. Your whole life in exile is in this box, he told me, reiterating: tarpaulins from UNICEF, 3 wood and gas burners, 5 chimney pipes for the burners, 2 carts, 1 folding metal bed, 7 felt mattresses, 8 wool blankets, and more.

***

We immerse ourselves in the darkness, silenced and blindfolded. In the dense, unfamiliar space, our movements are sluggish and precarious. Exposed and vulnerable, we encounter one another.

Translation: Anda Macbride

This text was originally published in The Grid and the Cloud, HISK Catalogue, 2017

Notes

- 1 The following works by Aslan Goisum are featured in the essay: Memories of War, 2016; Prospekt Pobedy, 2014; Volga, 2015; Gate, 2013; Household, 2016; Flag, 2015/16. Other artworks referred: K. Malevich, The Black Square, 1915; M. Abramović, Generator, 2014/17.