38 — July 2023

clustered | unclusteredThe (Em)Bracelet. Sentimental Mechanisms in Royal Jewellery.

Part 2 / 2 — Editors: Charlotte Vanhoubroeck, Arne De Winde

a

clustered | unclusteredA Conversation with Marius Kwint

Marius Kwint & Charlotte Vanhoubroeck

b

clustered | unclusteredSwipe to unlock

Ine Meganck

c

clustered | unclusteredWeep not it falls to rise again. Mourning jewellery and the marginalization of sentiments in art history and contemporary art jewellery.

Liesbeth den Besten

One of the first jewellery books I ever bought was Sentimental Jewellery, written by Shirly Bury and published by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 1985. From the handwriting of my inscription and the address in the book, I can deduce that I must have bought it shortly after its publication. At the time, I was merely interested in contemporary jewellery. But this book about sentimental jewellery caught my attention because of the combination of ‘sentimental’ and ‘jewellery’, which went against ideas I had about jewellery at that time. The deeper meanings of jewellery still had to be unlocked for me. The everyday jewellery of my mother didn’t interest me a bit, my own jewellery was cheap, fun, and not more than that, and historical jewellery was not yet within reach, while the contemporary jewellery I examined for my final thesis at university was far from sentimental.

When studying and analysing Dutch jewellery from the 1950s to the early 1980s within the context of art and design, I found interesting parallels between art movements (Conceptual, Abstract-Geometric, Minimal and Body Art) and design solutions. The attempt in the 1960s and 1970s to release the ingrained connection between jewellery and pecuniary value with the aim to renew the profession was topical and appealing. In this first formative period of contemporary jewellery there was a need for an objectified take on jewellery. The depiction and conception of jewellery as an object, often photographed as an unidentified single object in space, with no clues to dimensions and the human body, was an important stage in its emancipation. Jewellery needed to liberate itself from the client, from financial issues, and symbolical meanings. In this vision, the aspirations of the designers were central. It was exciting, it was new, it was young, and it was against traditions and conventions. And my own ideas about jewellery were totally in line with this vision. Consequently, sentimental jewellery remained untouched for quite some time.

The idea that jewellery can capture personal feelings of love and grief (in addition to expressing religious and political beliefs, and social designations) became only gradually important for me. My collection of contemporary jewellery (since 1982) is primarily instigated by aesthetic and artistic considerations. However, from the start I experienced the importance of wearing jewellery, of making it your own and finding personal meaning in it. Almost ten years ago, when my father’s health deteriorated, I asked Dutch jewellery artist Dinie Besems if she could make a piece of jewellery for me that would keep a memory of my father. Her sash made of Japanese glass beads captured a line of poetry by my father, who was a poet and critic (fig. 1). I wore the jewellery piece at his funeral, and later at other funerals or family gatherings. It was my first piece of contemporary sentimental jewellery.

Around that time, in 2015, my interest in nineteenth-century mourning jewellery caught on. The book that I had kept in my library for so long, helped me to understand the phenomenon of sentimental jewellery to some extent, as it gives a glimpse of the vast collection of sentimental jewellery at the V&A Museum in London. Sentimental culture, emerging in the mid-eighteenth century and continuing through most of the nineteenth century, is a product of European Enlightenment and points at a more personalized awareness of life. The growing popularity of jewellery as a sign of love, friendship, death, and remembrance, is part of this culture.

Miniature Portraits

Sentimental sepia miniatures, portrait miniatures (watercolour and photography), eye miniatures, and hairwork, are all expressions of a cult of sentimentality that started in the last decade of the eighteenth century and continued well into the nineteenth century. An important component of this sentimental culture is the exchange of miniature portraits, unwearable ones to keep in a cabinet or on the wall, and wearable portraits incorporated into jewellery.

Several scholars have noted that portrait miniatures and photographic portrait jewellery weren’t granted a high art status because they resided in overlapping categories: painting, photography, jewellery. Consequently, they ended up in a marginal and uncertain place in art history and thus in museum collections. Portrait miniatures in frames are classified as either painting or jewellery. However, both classifications are too rigid for a better understanding of these objects. If they are perceived as painting, it is within the sub-category of portraiture. Within this genre though, portrait miniatures are seen as a minor art, because of their dimensions and materials. According to Marcia Pointon, a watercolour miniature on ivory belongs to the margins of portraiture, which is generally associated with grand images and psychologically captivating depictions (Pointon, 48). If, however, the portrait miniatures are perceived as jewellery, it is because of their precious case or frame set with stones, pearls, and elaborated with other embellishments. But only observing these objects as jewellery pieces, ignores the substantive relationship between portrait and frame. Therefore, Pointon introduced the word “portrait-objects” to indicate “the interactive relationship between image and surround” (Pointon, 48).

Commissioning and exchanging portrait miniatures was a fashion that became quite popular among the elite around 1740 and continued until about 1840. As such this phenomenon reaches back to the 1520s and the courts of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I of England, where portrait miniatures were given to subjects who did a good service to a ruler. This portrait jewellery served as a propaganda tool as it forged loyalty. The execution of Charles I in 1649 generated a stream of commemorative jewellery, mostly rings, set with an enamelled miniature of the unlucky Stuart. However, contrary to what is sometimes claimed, these rings were not mourning jewellery. They had a political function and were worn (sometimes hidden) until well into the eighteenth century by royalists, hoping for the return of the Stuart monarchy (Scarisbrick, 188-190).

The new eighteenth-century fashion of portrait miniatures (fig. 2) emerged in England and spread to America and all over Europe. These portraits – either as full-scale easel paintings, miniatures, or in a written format – played a vital role in the life of the upper class. Men exchanged miniature portraits, as some sort of carte de visite, confirming social connections, like the age-old custom of diplomatic gifts at court. It was a way of establishing a new self-consciousness among the urban elite, also for those who emigrated to America. As Robin Jaffee Frank argues, “Miniatures crafted identities, elevated status, and cemented social bonds, giving a public gloss to a private art.” (Jaffee Frank, 5).

In many mid- to late-eighteenth-century full-scale portraits of women, a portrait miniature is a common ingredient, worn as a pendant from a ribbon, as a brooch or mounted on multi-stranded pearl bracelets. Mostly it is the husband who is depicted in these miniatures, showing the woman’s loyalty to him. In her article “Telling Objects – Miniatures as an Interactive Medium in Eighteenth-Century Female European Court Portraits”, Karin Schrader distinguishes different ways of wearing or displaying portrait miniatures in large-scale portraits, according to their function as symbols of luxury, status, affiliation, loyalty, propaganda as well as personal sentiment. She discusses different gestures of pointing, holding and touching, positions of an arm or a hand, and gazes directed at the portrait miniature. Schrader dissects all these gestures and gazes with the aim of developing narratives about loyalty, lineage, mistresses, illegitimate children, and dynastic claims. Some paintings depict women (sometimes men) gazing at miniature portraits held in their hands, while also a letter is depicted. This popular iconography testifies that portrait miniatures functioned in an intimate way. From letters, literature, and poetry too we know that hand-hold miniature portraits are quintessentially about the self and the other. As Pointon explains: “The word gaze in this period denotes a fixity of looking or staring that implies a degree of self-consciousness on the part of the looker and the looked at.” (Pointon, 63). Hanneke Grootenboer sees the portrait miniature as a remarkable and underestimated case in the history of vision, for which she introduces the term intimate vision: “Ultimately, intimate vision provides an intimate space in which painting serves as the mise-en-scene for an encounter that allows us to fall back on ourselves.” (Grootenboer, 2012: 5). Correspondingly, portrait miniatures were kept in cases or worn as jewellery (only by women, not by men) that could be held in the hand or shown in public as intimate objects of affection. Besides this, miniature portraits were also displayed in cabinets or on the wall. It is known that some families had portraits made of all family members in different stages of their life, which were exhibited semi-publicly at home. Also, miniature portraits of acquaintances and friends were displayed at home.

Robin Jaffee Frank’s book about portrait miniatures, primarily based on the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, gives an impression of the immense popularity and proliferation of these types of objects. Other museums such as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam have huge collections of mostly anonymous eighteenth-century portrait miniatures. It seems like the second half of the eighteenth century was rather obsessed with portraits. Why? Obviously, miniature portraits were made to cherish a bond between the sitter and the beholder. Considering miniature portrait jewellery within the context of castles and mansions abundant with ancient portrait paintings on every wall and in every room, staircase, and hallway, Pointon sees the meaning of it in “the construction of personhood, the identity of the individual subject” (Pointon, 68). In other words, the miniature portrait shows that the owner, at the same time, is socially connected with family and a network of friends and acquaintances, and is an independent individual. Contrary to large portrait paintings, the miniature portrait could be held in the hands, touched, and even worn on the body. This way it offered a space for contemplation and sentimental expression that was highly appreciated by lovers, friends, brothers and sisters, parents and children who were separated from each other for a certain period or the rest of their life.

Within the miniature portraits category, eye miniatures are a class of their own, which we might call a superlative form of portrait miniatures (fig. 3). According to Hanneke Grootenboer, the eye miniature, a short-lived phenomenon between about 1785 and 1830, is not just a miniature watercolour painting on ivory of someone’s eye but a portrait of someone’s gaze that absorbs the person looking at it to such an extent that subject and object become one. She writes that it is not clear “who exactly does the looking here. Is it us, examining the tiny pictures, or are these spooky eyes exclusively there to watch us?” (Grootenboer, 2012: 21) In the eighteenth century, women were not supposed to talk with unknown gentlemen in public. Thus, watching and gazing was an accepted social game based on unwritten rules of “the knowing eye of the gentleman” and “a necessarily conscious act on the women’s part” (Ylivuori, 115). In a gazing culture like this, a miniature of one eye must have had a great impact on the receiver/beholder. Natalie Nicolaides even characterizes it as “the soul of the loved one” (Nicolaides, 6). A famous example is the effect the eye miniature of the Prince of Wales had, when it was sent to his adored Mrs. Fitzherbert in 1784: Fitzherbert, who had fled to the continent under the pressure of the prince’s advances, surrendered, returned to England, and secretly married the prince.

Mourning Jewellery

Because of the cult of sentimentality around 1800, weeping was considered a natural virtue, even in public and even by men. By the end of the eighteenth century a new mourning iconography came into being that sublimated grief. In this vein, mourning jewellery, which was most often painted in sepia on ivory, shows monuments, weeping women, tombs, urns, obelisks, broken pillars, weeping willows, and cypresses. A beautiful example is a locket made to commemorate S. C. Washington, who died in 1789 aged nineteen, and shows a depiction of the young woman breaking from her tomb while her mother is waiting for her (fig. 4). Texts that express deep feelings of sorrow and trust in a reunion after death were also added: “NOT LOST BUT GONE BEFORE” (fig. 5); “TO ME HE WILL NEVER DIE; SACRED WILL I KEEP THY DEAR REMAINS; PREPARE TO FOLLOW; WEEP NOT IT FALLS TO RISE AGAIN” (fig. 6), or “MAY SAINTS EMBRACE THEE WITH A LOVE LIKE MINE”. The texts are partly addressed to the deceased person, and partly to the survivors. The reverse side of these jewellery pieces often shows hairwork.

Fig. 6 (r): Commemorative brooch with text “Weep Not It Falls to Rise Again”, ca. 1800, enamelled gold frame, gold, painted miniature, embellished with ivory, gold foil, hair, collection Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Jaffee Frank sees the eighteenth-century miniature portrait tradition as a precursor of the mourning jewel because of the miniature’s ability to evoke the other: “The physical characteristics of miniatures embody their role as substitutes for the beloved.” (Jaffee Frank, 7). Equally, Pointon argues that “[p]ortrait gifts, we may infer, not only represent people, they also stand in their stead” (Pointon, 57). This applies to bonds of friendship and love but can also be applied to a deceased person. Consequently, in the Victorian era, the fashion of wearing a miniature portrait was gradually substituted by the new trend of wearing mourning jewellery. After 1840, photography gradually substituted the hand-painted miniature. Early daguerreotype portraits were sometimes advertised as ‘daguerreotype miniatures’. Most oval daguerreotype portraits were held in rectangular frames, reminding of gilded picture frames, which were kept in hinged leather cases just like painted miniatures (Strickler and Krichevsky, 4). But daguerreotype portraits were also made into pendants and brooches (fig. 7). During a period of overlap, when painted miniature portraitures were still in fashion, portrait photographs were sometimes partly coloured (such as the cheeks, the jewellery and costume) (fig. 8). When the daguerreotype was replaced by other more advanced and accessible types of photography, these portraits very rapidly superseded painted miniatures. What remained was the oval design of lockets and the integration of hairwork on the reverse. In keeping with the more accessible nature of photography, the frames were mostly of low-grade gold, sometimes embellished with enamel.

Hairwork

As already indicated, hairwork (fig. 9) was often applied on the reverse of a portrait miniature (since about 1740) or a portrait photograph (since about 1840). Whether these portraits with hairwork are mourning jewellery or a sign of love or affection is often difficult to determine, especially when further symbols, inscriptions or any other information about origin and ownership are missing. In general, the connection between hair and grief seems to have been widely accepted, although there is also a category of friendship and love jewellery with integrated hairwork. In both cases, hair, as bodily material, represents the person it belonged to, either (secretly) beloved or deceased, and functions as a relic. Contrary to the rest of the human body, hair does not perish, nor lose its colour, and therefore was associated with eternal life. In popular belief hair was considered the seat of the soul and life. It should therefore be cut before someone died, only then retaining its magical power as the sheath of the soul of the deceased. Hair was considered a magical material, especially before the invention of photography, when it was often the only tangible trace left of a beloved one. When photography was introduced as an even better memento of a deceased person (it was more similar and more real than a painted portrait), hair became its common companion – following the design of the earlier miniature portraits.

In eighteenth-century mourning jewellery, hair was often used to embellish a painted (sepia) miniature with a mourning scene. Chopped hair was used to paint groves or weeping willows, while bundles of hair were used to depict a tree, wheatsheaf, cross, garlands, or funeral wreaths (fig. 10). Iconographically more generic mourning jewellery mostly concerned a medallion with a miniature (or, later on, a photo) on one side, a hairwork on the other side (both set under glass), and an ornamented frame; sometimes initials or a text were added to the hairwork or on the frame. In more complex designs the hairwork was embellished with refined ornaments of gold wire and seed pearls. The hair of the lost one was made into a small artwork of woven or braided hair or was made into artful compositions called Prince of Wales Feathers or Curls (fig. 11) – an interesting example of ‘palette-work’. The name refers to the heraldic badge of the English Prince of Wales, consisting of three swooping ostrich feathers. Why the emblem was adopted in mourning jewellery is a mystery. I assume that in the eighteenth century the emblem was probably only used in portrait miniatures that were a sign of love, friendship or affection, as a reference to the extravagant Prince of Wales, later King George IV (1762 – 1830), and his appealing love story with Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert. Later in history, when the association with the prince became less obvious, I suppose the curls had become so popular that they were used in mourning jewellery as well. In the nineteenth century hair was applied in a ‘table-worked’, woven or braided manner, in different patterns, sometimes including different hair colours. A new, innovative technique of open hairwork resulted in bracelets, necklaces, pendants, and brooches of three-dimensionally woven or braided human hair, finished with golden details and clasps.

Clearly, hair is an important component of mourning jewellery, but Rachel Robertson Harmeyer explains that the social use of hair in any kind of jewellery, including miniature portraits, could also be a sign of love or familial affection. However, signs could also be misinterpreted. To exemplify this, she discusses two extracts from Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility (1811), which show the social significance of hair as ‘authenticator’ of a special connection to an individual (Robertson Harmeyer, 29). From these examples we learn that a man could wear a ring in public with a plaited hairwork belonging to his sister, which was misinterpreted by others as a hairwork of a secret lover. Both scenarios were possible, there were no rules. In fact, the significance of (hair) jewellery such as this ring could easily shift, for example from a sign of affection to a memento.

Interestingly, hairwork was not confined to jewellery, it was also applied in skillfully homemade ‘family trees’, wreaths, and other objects that included hair of a whole family or a circle of friends (fig. 12). During the nineteenth century, hairwork became so popular that the craft was no longer left to professionals alone. An interesting Dutch mourning brooch with a painted scene including chopped hair on one side and a bowl of fruit and flowers made of hair and paper on the other side, was – according to a note on the inside – made by an Utrecht bookbinder in 1833 (fig. 13). In the course of the nineteenth century, thanks to sample books, manuals, and articles in women’s magazines, hairwork became the domain of women who adopted it as a hobby. Partly because of this tendency, the subject did not find its rightful place in art history or the history of decorative arts. In her dissertation about hairwork, Robertson Harmeyer rightly argues: “Hairwork is an interdisciplinary object and subject by default because of how the disciplines have been defined, predetermined by the institutional history of the hierarchy of genres and the relegation of anything appearing to be ‘women’s work’ (amateur craft, expressions of sentiment and grief, the act of adorning the body and the home) to the dustbin of history.” (Robertson Harmeyer, 3). We can add hairwork to Robertson Harmeyer’s list of disregarded ‘women’s work’. Moreover, in the nineteenth century, jewellery was increasingly considered the domain of women, a legacy which led to deep traces of absence in art history. None of this helped to give mourning jewellery and hairwork the place in art history it deserves.

Eventually, the art of hairwork was abandoned rather abruptly at the end of the nineteenth century and then fell into oblivion. During the twentieth century, hair jewellery was qualified as macabre and distasteful, and observed with a mixture of horror and fascination. The disdain for mourning jewellery and hairwork corresponds with the twentieth-century conception of the Victorian era as a period of bad taste, exaggeration, and excessive sentimentalism. However, during the last decades the scholarly interest in the subject has grown exponentially.

Mourning Jewellery Industry

In the nineteenth century, when people were supposed to actively and publicly display their grief, relatives and sometimes close friends had jewellery made to remember a loved one. After the death of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert in 1861, mourning became a matter of protocol. Everyone at court was obliged to wear mourning dress on social occasions until the end of 1864. Ladies-in-waiting habitually wore black, the other ladies could wear half-mourning dress (Bury, 32). In the daily life of the middle class and elite, mourning became subject to strict rules, depending on the relationship with the deceased. A widow withdrew from public life and wore clothing and jewellery that evolved from ‘deep’ or ‘full’ mourning, to ‘second’ or ‘half mourning’, and eventually to ‘light mourning’. The smallest details counted, even the pins that were used to fasten parts of the clothing had to be pitch black. These pins were produced in huge quantities in England and abroad (fig. 14).

The death of Prince Albert in England, and the American Civil War of 1861-1865, which took about 700.000 lives, gave a new impetus to the mourning jewellery industry. The mourning industry was diverse, from small specialist workshops (artisans) working to order and workshops using generic samples, to factories where large quantities of black non-precious jewellery were produced using the latest technological and material innovations. Swivel brooches, which could rotate on their axis, were a very popular innovation. Black became a fashion, and many black materials were adopted for making mourning jewellery: gutta-percha (a thermoplastic latex derived from a tropical tree), Irish bog oak, Whitby jet (found only in Whitby, North Yorkshire, where it is used since the Neolithic period), dyed horn, faceted black glass (called French jet), vulcanite, ebonite, and more. Most materials could be moulded, but Whitby jet (a fossilized wood) was hard as stone and lathe-worked with hand-carved details. Mourning became fashion. Some industrially produced black-beaded necklaces are so elaborate and excessive in their design that we might question their status as mourning jewellery. These necklaces seem more at home in the world of fashion, as real statement pieces. As a result, the mourning industry in clothing and jewellery boomed in the Victorian era, in the UK, America and Europe. An industrial city like Birmingham profited tremendously from this. Regent Street in London was the place where one could find Jay & Co, a huge mourning warehouse, and several hairworkers. Mourning was a cult that made crafts, business, and industry thrive, and ensured material and technical innovations.

Conclusion

Shirley Bury (1925-1999), former curator of the Department of Metalwork at the Victoria & Albert Museum, was one of the first theorists who published a serious study on sentimental (including mourning) jewellery. Her publication pointed the way for me as an expert, a collector, and lover of contemporary art jewellery, to sentimental jewellery.

What struck me, when studying the subject more deeply, is the fact that there is still a lot unclear about the connection between early miniature portraits and nineteenth-century mourning jewellery. Yet, we can discern a clear evolution. From the sixteenth and seventeenth century onwards, painted portrait miniatures were distributed at court as tokens of loyalty, or worn as a political statement. Throughout the eighteenth century, painted portrait miniatures served as tokens of love, affection, and social connectedness among the nobility and upper middle class. Subsequently, photographic portraits functioning as mourning and memento jewellery became accessible to larger parts of the population in England, America, and Europe. We can distinguish two important developments that played an essential role here. Firstly, there was a spiritual development at the end of the eighteenth century and during the romantic era, which gave room to a culture of sentimentality, in which personal, subjective feelings and introspection took centre stage. In this climate the parting or passing of a beloved friend or family member could become a theme in jewellery. Secondly, there was the increasing industrialization and technical progress of the nineteenth century, which encouraged novelties and innovation, such as the invention of photography. When we add to this the high death toll because of poverty, hunger, unsanitary conditions in the crowded cities, infectious diseases, workplace accidents and wars such as the American Civil War, we understand why photography portraits in jewellery became so popular in the nineteenth century. The iconographic layout for this kind of jewellery was already in place, so to speak. The two-sided historical miniature portrait with its meaningful back, served as a blueprint for nineteenth-century innovations.

When I became interested in jewellery (around 1980), the dichotomy between sentimentality and modernity was at its peak. Modernist designers didn’t care about personal feelings. Their motto was the rationality of design and choice of materials. By renouncing the past, the way could be cleared for new or ‘modern’ jewellery. The discourse about the meaningful social function of jewellery was blocked rigorously. In a discussion published in a Dutch art magazine, Gijs Bakker, one of the protagonists and innovators of jewellery in the 1960s, refers to “the sentimental, historical” way of dealing with jewellery, which he and his like-minded wife and jewellery designer Emmy van Leersum resolutely rejected (Colmjon, 175). One of the subjects Bakker in this article constantly insists on is the freedom of artists to make what they want, without taking the wearer into account. All the wearer was asked to do was consent to the concept and the form of the piece. This vision formed the basis of contemporary jewellery as an art form. In this context ‘sentimental’ was labelled as a negative quality, while references to history were to be avoided. But by studying the history of jewellery more thoroughly and thoughtfully I learned how jewellery has always been embedded in social life and has therefore always been an essential part of sentimental culture, customs, gestures, and spirituality. I am convinced that contemporary art jewellery can gain from this insight and use it, without losing its artistic integrity and idiosyncrasy – as the example of Dinie Besems’s jewellery (2015) demonstrates.

References

- Shirley Bury, S. (1985). An Introduction to Sentimental Jewellery, London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

- Colmjon, G. van (1986). Een onpersoonlijk lijf tegenover de borst van Rob van Koningsbruggen. Godert van Colmjon in gesprek met Gijs Bakker en Robert Smit. Museumjournaal, No. 3 & 4, p. 169-179.

- Jaffee Frank, R. (2000). Love and Loss, American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Grootenboer, H. (2006). Treasuring the Gaze: Eye Miniature Portraits and the Intimacy of Vision. The Art Bulletin, Vol. 88, No. 3, pp. 496-507.

- Grootenboer, H. (2012). Treasuring the Gaze, Intimate Vision in Late Eighteenth Century Eye Miniatures. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Nicolaides, N. (no year). The Invasive Eye, The Amusement of our Audiences and / or a Severe Case of Misplaced Identity. London: Kingston University.

- Pointon, M. (2001). Surrounded with Brilliants: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England. The Art Bulletin, Vol. 83, No.1, pp.48-71.

- Robertson Harmeyer, R. (2013). The Hair as Remembrancer: Hairwork and the Technology of Memory. Thesis. Houston: Faculty of the Department of Art History University of Houston.

- Scarisbrick, D. (2007). Rings. Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Schrader, K. (2019). Telling Objects: Miniatures as an Interactive Medium in Eighteenth-Century Female European Court Portraits. Études Épistémè, Revue de littérature et de civilization (XVI-XVIIIe siècles), 36, pp 1-27.

- Strickler, S.; Krichevsky, T. (2018). Intimate Keepsakes. American Portrait Miniatures. A Gift from Charles A. Gilday. Manchester, New Hampshire: Currier Museum of Art.

- Van Strien, K. (2019). Belle van Zuylen, een leven in Holland. Soesterberg: Aspect.

- Ylivuori S. (2019). Women and Politeness in Eighteenth-Century England. Bodies, Identities, and Power. London, New York: Routledge.

d

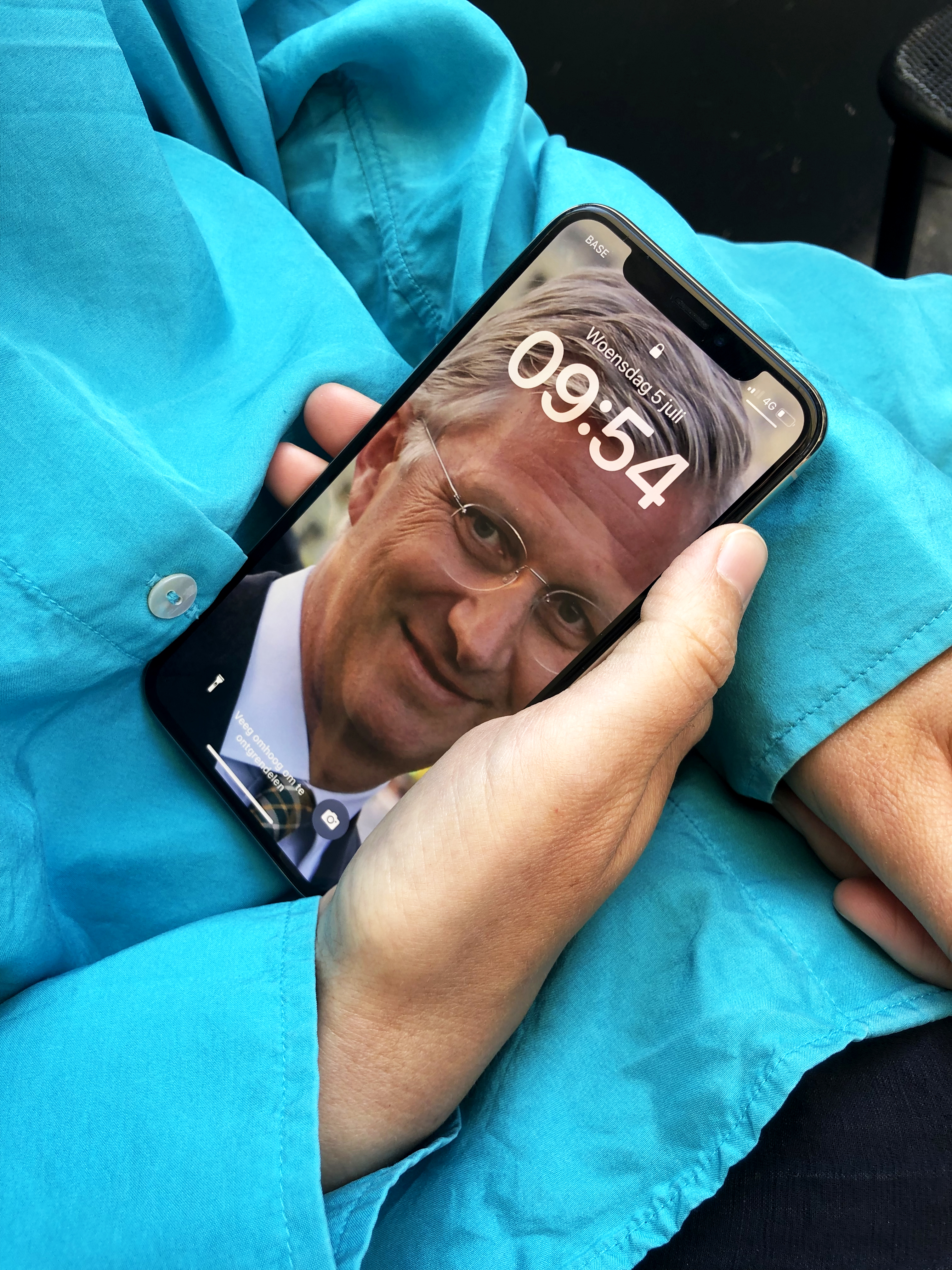

clustered | unclusteredN° 4 – N° 113?

Charlotte Vanhoubroeck

“N° 4 – N° 113?” Hybrid Brooch Sterling silver, glass Stilled Sentiments collection 2021

Jewellery piece created according to the following Estate Inventory descriptions (1851):

N° 4 – « Un bracelet avec le portrait du Roi, entouré de brillants, tour de bras avec modèle, gourmette avec chaînon en brillants. »

N° 113 – « Un médaillon formé du portrait de Sa Majesté Le Roi Léopold, entouré de dix huit brillants avec un anneau orné de cinq brillants plus petits. »