54 — June 2020

Deorientalize, Now More than Ever!

Maha El Hissy

For a few months in 2017, during my time as a visiting research scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, the University Library showed an exhibit named “A Country Called Syria.”1 Central to the small collection of artefacts was an ensemble comprising a figurine of a man dressed in oriental clothes and hand weaving, a tapa, and a fez (figure 1 and 2). Further exhibits included some daggers and pictures in a number of opened books placed near the entrance hall in vitrines to give passers-by a quick impression of this country’s “ancient history and diversity while at the same time also paying attention to modern Syria with all its complexities,”2 as the Library advertised on its website. It is perhaps tiresome to have to repeat in the 21st century a list of arguments against such generalizing depictions of a geographical region comprising various countries with very diverse cultural, linguistic, social, political and religious backgrounds as one homogenous entity. This is not to mention the lack of consideration for the complexity of that region, any traces of what could qualify roughly as being close to modern. This is all the more perplexing, given the fact that these exhibits where placed at the library of one of the top universities worldwide. While this selective, essentialising, exoticizing, romanticizing portrayal of the Orient is advertised as “modern” and is still ongoing, in the same enduring style as the 18th and 19th century imperialist depictions Edward Said analysed in the late 1970s in Orientalism, the founding text depicting this Orientalist discourse, there have been repeated calls recently to shelve Said’s work, together with postcolonial theory in general, as outdated and passé.3 Some of this critique highlights how postcolonial theory barely had any significant achievements, how Said’s Orientalist critique would cement Othering, or that postcolonial studies and theory were important by the time when they were founded a few decades ago but are now outdated.4 Is this true? Is it no longer the case that the Orient is fantasized in the West as barbaric, uncivilized, inferior, dangerous, seductive, untamed, unruly, primitive and obsolescent?

In reference to this collection – an example of an elite university library (after all, the symbolic place for archiving and organizing knowledge), appropriating knowledge of the Other that continues to evoke Orientalist fantasies – my answer is evidently no. Instead, I want to argue that this Orientalist pattern that divides the world into East and West has not been abandoned; instead, it is revived in times of (cultural) crisis, by which I mean a crisis of representation, including an absence of self-representation.

Figure 2 (right): A tapa and a fez

This collection is a quintessential example of what a crisis of representation entails. Picturing a “country called Syria” and giving bystanders an exoticized glimpse into its history, heritage and culture seems more severe, even fatal, if you take into account that this Orientalist form of representation is in fact referring to a post-war Syria. Hence, the Western practice of appropriating knowledge about the Other by showing completely benign, quaint images occurs during a time when the international community has failed the Syrian nation in one of the deadliest wars in the 21st century. The choice of artefacts blanks out the horrific reality of this war that the United States is also involved in, and opts instead to present an Oriental fairy-tale drawing on visions from The Thousand and One Nights. In fact, the website providing information about the exhibition states the idea behind their choices, with clear reference to their intention to avoid the Syrian war: “we all thought it would be a good idea to showcase aspects of the country and the people other than the depressing ones covered in the news.”5

My critique of this Orientalist selection does not imply that all exhibits on Syria must refer to the war. It does not only concern the representational strategy of concealing the war, which is a genuine faux pas, but the specific preference and choice of an Orientalist portrayal. For if the decision can be understood, according to the website, as an artistic coping mechanism, the question remains: why not display aspects of modern life in Syria, such as contemporary artwork by the artists Khaled Takreti, Safwan Dahoul, or Nihad A-Turk; or make reference to modern Arab literature, for instance, by Adonis, Nizar Qabbani, Haidar Haidar, Hanna Mina, Zakaryyia Tamer, or Ghada al-Samman? This apparently arbitrary and reductive curation indicates that the choice of an Orientalist model is also a result of a crisis of knowledge of the Other – a crisis that erupts as this region remains a dark area, a space for the well-known projections of modern West versus archaic East. This is when the same old depiction is repeatedly reinvigorated: to fill a vacuum and renew the imperialist idea of possessing knowledge about what is imagined to be an inferior Other.

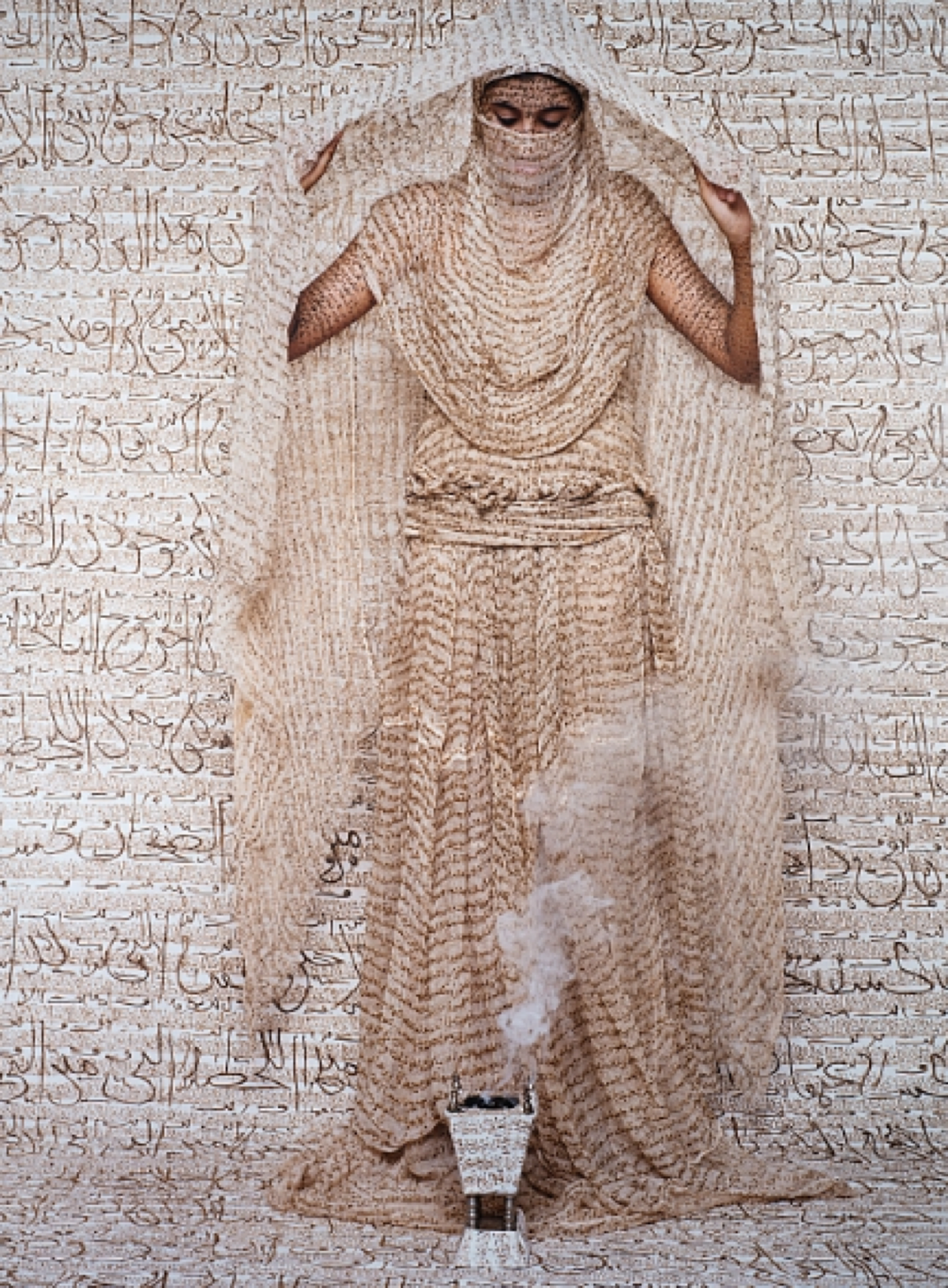

The Orient: A No-face

Remarkably, this Orientalist representation, like many others, including a number of current exhibitions on the Orient in various German museums,6 is faceless and anonymous, by which I mean that the visitor cannot learn much about what the Oriental Other looks like – not to speak of Oriental women, who can hardly be seen at all, and are imagined as confined somewhere in a harem or a hammam, subordinate or eroticized within a patriarchal structure. The visual arrangements around these exhibitions perpetuate the mechanisms of the colonial gaze, which separates the colonizer from the colonized by clearly attributing the power of representation to the colonizer. Among the websites advertising Oriental exhibitions in different museums in Germany, one of the very few examples that do indeed show a face, at the “Museum Fünf Kontinente”, once again opens up a space for fantasies and projections (figure 3). A woman dressed in sepia tones poses with a veil that covers her head, while the bare skin of her brown arms can still be recognized, with a sense of mystery evoking longing, desire and taboo. The depicted model is posed behind, of all things, an incense burner and in front of a wall covered with Arabic script, in what might (incorrectly) be thought to be verses from the Quran, adding to the enigmatic and mystifying effect of the whole scene. This image is part of an exhibition running under a name that could not be more programmatic: “Der Orient. Zum Staunen so nah”, or “The Orient. So Close to Marvel”7. This practice of appropriating the Other, suggesting that it is brought close to viewers and basing it on fantasies of longing and desire while eradicating forms of self-representation, is an act of violence. As Edward Said notes: “The act of representing others almost always involves violence to the subject of representation.”8 As I explore below, self-representation is the only means to put an end to such a violent act, which I will discuss further in the next section.

There could have been an exhibit about contemporary feminist Arab writing by the Lebanese Joumana Haddad, or Fatema Mernissi, one of the world’s leading Islamic feminists from Morocco, for instance; or references to broadcasting such as “Hammam Radio,” a feminist participatory project launched in Berlin9, or a photo exhibition of women in the Arab Spring. Why does this Orientalist representation of women persist? Postcolonial theory, which many like to see as out of date, teaches us that colonized women of colour rank at the bottom of a colonial hierarchy, while the white man sits enthroned on top, followed by the white woman and then men of colour. Even though the structure of such a pyramid simplifies matters and leaves out important factors (such as the impact of class), one could argue that this Orientalist depiction of women is revived in times of crisis, when this hierarchical order of patriarchy is threatened or endangered. White feminism would exemplify how such a mechanism of power works: the focus on the struggle of white women against male patriarchy, neglects the battle by other Women of Colour and negotiates white claims by cementing the position of Black and People of Colour as subordinate. Hence, the calls for decolonizing are met with attempts to consolidate a structure of power that exercises othering. Only self-representation can destabilize this robust and enduring structure.

Re:Orient, or, Strip Off: Towards Deorientalizing

To challenge this regime of representation, the GRASSI Museum für Völkerkunde in Leipzig hosted the exhibition “RE:Orient – die Erfindung des muslimischen Anderen” (RE:Orient – the creation of the Muslim Other) by artists from Turkey, Lebanon, Germany, and UAE.10 The exhibition clearly contrasts with the Orientalist practices by many museums in Germany as it is subversive, gives women a face, and performs against the grain. As the program of the exhibition indicates, Re:Orient aims at redirecting the viewer to highlight what is usually easily overlooked or ignored: “‘Re:Orient – Die Erfindung des muslimischen Anderen’ ist eine Reorientierung hin zu dem, was im Schauen auf ‘die Anderen’ allzu häufig ungesehen bleibt.” (“‘Re:Orient – The invention of the Muslim Other’ is a reorientation to everything that often goes unnoticed when observing the Other.”)11

Figure 5 (right): Gülcan Turna, Reenacting The Empress? Power To The People. What Are We For? The Turkish Artist As An Empress, 2019

In what could be regarded as a revolutionary pose, the artist Isra Abdou is seen wearing an orange wig on top of her veil (Figure 4). This unusual headgear underlines that women are free to choose for themselves how they wish to wear their veil – an issue that the artist has focused on in one of her other art projects.12 Dressed in a suit, Isra Abdou is moreover asking employers to hire her, while alluding to the discrimination that Muslim women wearing a headscarf often have to face in their professional life, which has roots in the long-lasting stereotypes briefly discussed above. The upright sitting position, with a gaze confidently directed towards the viewer, suggests that professional qualities and achievements go unnoticed, overshadowed by the female subject’s personal beliefs, in this case by wearing a headscarf. Wearing a wig in a loud colour, which could make the viewer at first glance easily miss the piece of clothing placed underneath it, confronts the viewer (or the employer) with the anti-Muslim racism that is prevalent in the job market.

This example of self-representation is still engaged in opposing violent practices of appropriation and representing the Other, which means it is still involved in using the exact same instruments that it criticizes. The last picture or performance I want to discuss here is Gülcan Turna’s, and it explains this further (figure 4). The female artist adopts some elements of Oriental clichés, such as the hookah and posing in a hammam, while she opposes the popular phantasies of the Orient by turning the setting into a satire: the artist poses as the Statue of Liberty, her lower body covered with water while her clothing hangs open to reveal a bare breast. “Re:Orient” illustrates what a decisive step towards deorientalizing could possibly look like: a practice of self-representation and self-depiction. As the example shows, the Oriental Other has a face, one that is non-archaic. You see modern and fashionable women, who have a voice of their own to express their criticism of discrimination or plea for equality in professional life.

The abovementioned exhibition practices are pervasive and can be found when advertising academic Middle Eastern studies, for example, by showing a camel and an Oriental bazar.13 My plea to deorientalize academic curricula, museums, libraries, and in general our minds requires going even one more step further than the subversive exhibition in Leipzig by not responding to, or depending on any of the imposed arrangements of representation. Deorientalizing – which could be regarded as part of the larger project of decolonizing – refers to self-representation by creation and not as a response to the Western image of the Orient, for example – not by reusing, rewriting, or re-enacting. Many political demands during the Arab Spring, for example, were expressed genuinely using local songs, lyrics, poems, Arab hip-hop, etc. that are part of the popular regional culture. However, they remain unnoticed and underrepresented. While the strategies to draw on established representations made sense a few decades ago, during the time when postcolonial theory was founded, the call to deorientalize today means to open up unoccupied spaces of representation – with the references to colonialism that the word entails.

Notes

- 1Check for more information on the background

- 2https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/2017/05/18/new-exhibit-a-country-called-syria/

- 3See for instance the interview with Vivek Chibber on “Deutschlandfunk Kultur” published on 17.11.2019 (accessed on 20.06.2020), or Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s article “Das Ende der Postkolonialisten” published in “Die Welt” on 29.05.2020 (accessed on 20.06.2020)

- 4See the abovementioned interview with Chibber on “Deutschland Kultur” (17.11.2019)

- 5https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/2017/05/18/new-exhibit-a-country-called-syria/

- 6See, for example, the exhibition “Nurnberg and the Orient” in the city of Nurnberg; an Orient exhibition at the Linden Museum in Stuttgart; or the abovementioned “Museum Fünf Kontinente” in Munich with the exhibition “Der Orient. Zum Staunen so nah”

- 7https://www.museum-fuenf-kontinente.de/ausstellungen/der-orient.-zum-staunen-so-nah/

- 8Edward Said, “In the Shadow of the West”, Wedge 7-8 (1985), p. 4.

- 9https://yamakan.place/hammamradio/

- 10https://grassi-voelkerkunde.skd.museum/ausstellungen/reorient/

- 11https://grassi-voelkerkunde.skd.museum/ausstellungen/reorient/

- 12See the contribution by Rhea Dehn accompanying the exhibition on “Contemporary Muslim Fashion”: Der Schleier: Nexus zwischen Kunst und Mode. Ausstellungskatalog, Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt, p. 29

- 13Trinity College Dublin advertises Middle Eastern Studies with a clip showing a camel, an Oriental bazar, Andalusian tiles, while a lute can be heard playing in the background