34 – April 2021

clustered | unclustered

Methodologies in Artistic Research

Editors: Arne De Winde & Lieven Van Speybroeck

In the two decades that artistic research has existed in Flanders within an academic environment, discussion about what is an artistic versus a discursive methodology, “productive” versus “reflective” research, has never abated. And that is a good thing, as consensus in art is always suspect. That is also the reason a day spent examining the methodology of artistic research is still relevant today. The goal is not to reinvent the wheel, but to show an interesting combination of, on the one hand, hands-on methods of artistic researchers and, on the other hand, reflections about methodology that start from the specific observations in the workplace, studio, stage, editing room, study room, and so forth. For several years, “artistic research” has been given a more important role in arts education programs. Therefore, it is very useful to take a closer look at and interpret the methodological bottlenecks for artists-as-researchers from a pedagogical point of view. Perhaps a beginning to a solution can be found – a solution that will always be specific and very seldom generic.

This cluster is a collection of contributions based on the lectures given at a symposium on artistic research and methodologies on the 26th of April 2021. This event — a live stream that was broadcasted from the Kaaitheater in Brussels — was organised by PXL-MAD School of Arts, UHasselt, RITCS, Royal Conservatory Brussels, VUB and Brussels Art Platform. A recording of the whole stream can be watched here.

a

clustered | unclusteredResearch Environments

Joost Vanmaele, Agency, Katinka de Jonge, Amber Vanluffelen

De vrolijke wetenschap beperkt zich niet enkel tot het verstand, maar richt zich op alle aspecten van onze lichamelijke relatie tot onze omgeving – we verwerven een dergelijke kennis immers niet enkel via ideeën en beelden, maar ook via sensaties, affecten, stemmingen, emoties en verlangens.

— Kris Pint, De wilde tuin van de verbeelding (2017)

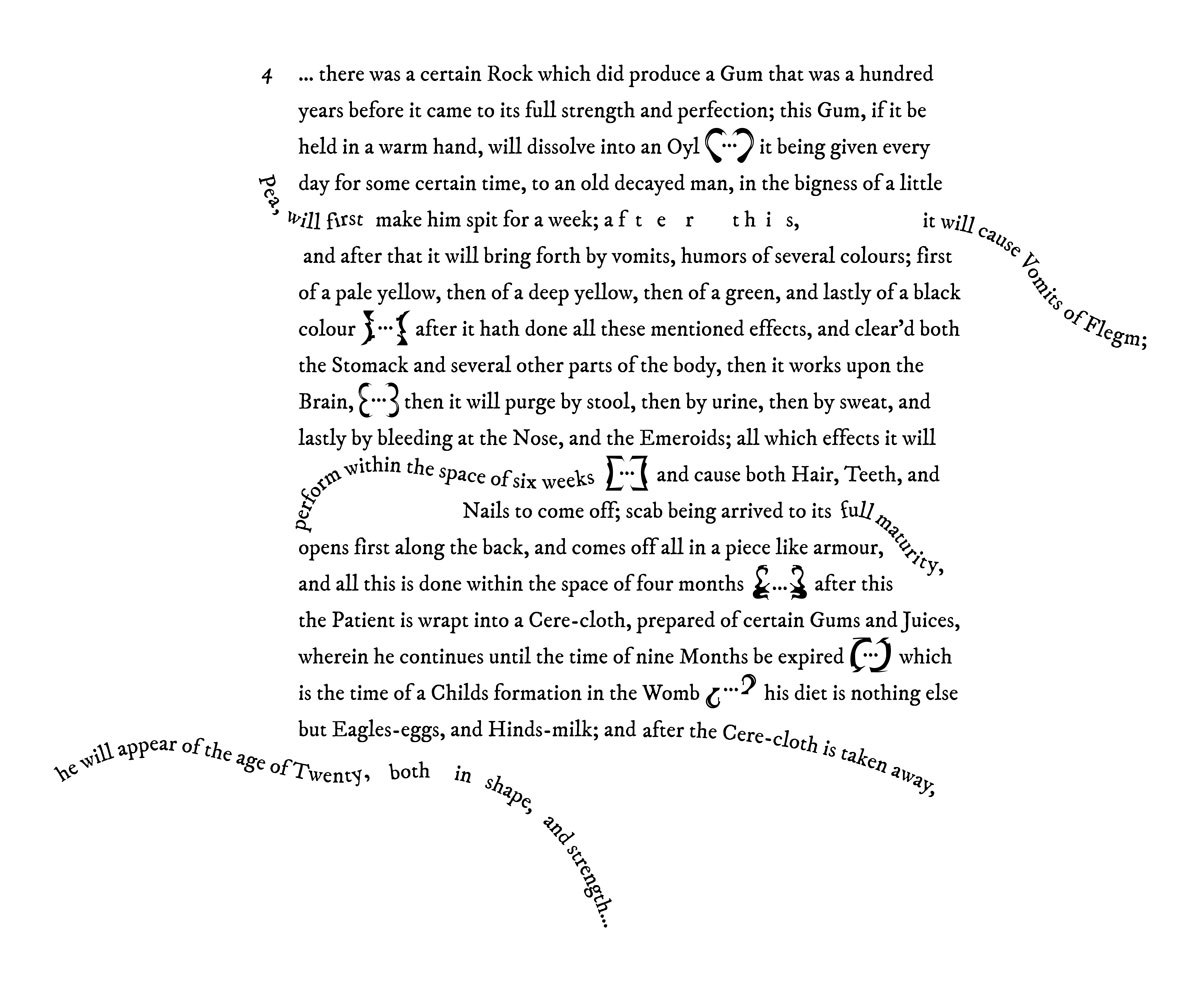

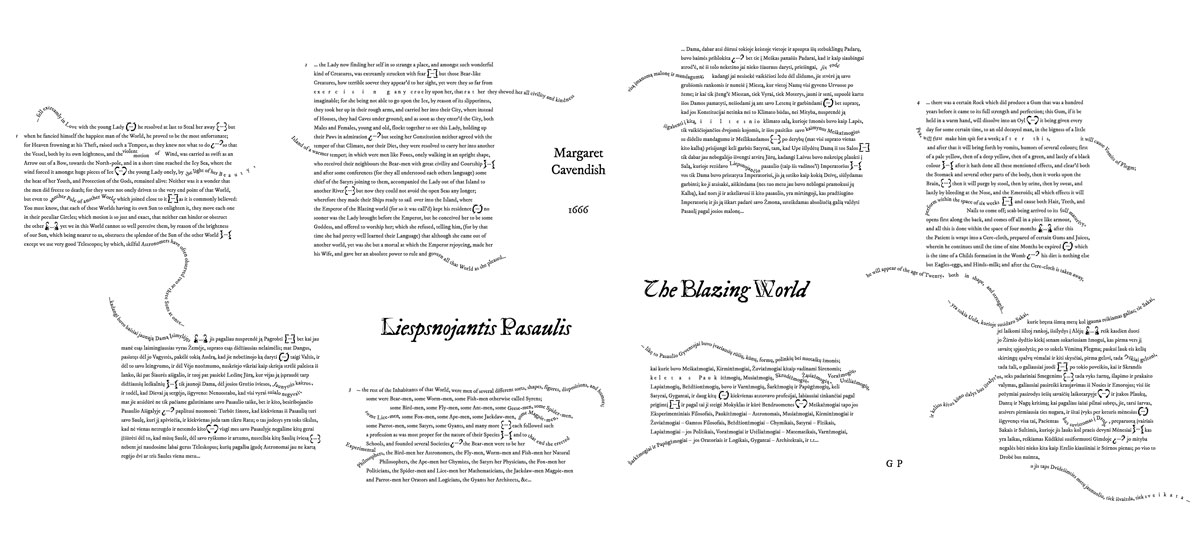

Methodonomy: Navigating the Space of Artistic Research

Joost Vanmaele

Excerpt from “Forever Young,” opening speech at Though this be madness, yet there is method in it, Symposium on Methodologies in Artistic Research, 26 April 2021, Kaaitheater Brussels

My approach to the question of artistic research takes its cue from the frequent use of the preposition ‘versus’ in the text that announces this event: artistic versus a discursive methodology, productive versus reflective research. It is the theme of relation where ‘versus’ points to a relation of conflict, a stand-off with a potential winner or with no winners at all in the case of a status quo.

Further on, we find three small connecting words in the title of this symposium, which also refer to a specific type of relation or connection:

though this be madness, yet there is method in it.

In the Oxford English Dictionary ‘though’ in combination with ‘yet’ is defined as:

An adversative particle expressing that relation of two opposed facts or circumstances […] in which the one is inadequate to prevent the other, and therefore both concur, contrary to what might be expected.

This comes close to what we would call a contradictio in terminis, an apparent but not a real contradiction — a relational situation where one cannot do without the other.

This close link is even more strongly articulated by the preposition ‘in’. Method, then, is considered to intrinsically belong to madness. It is a relation of close belonging and embeddedness.

We are all familiar with the fascination that artistic research, a concept that does not necessarily include a specific relational link or preposition, seems to have with exploring small words that can shed light on the connection between the world of art and the one of academia. Research on, for, in and through the arts are alle options that have been extensively examined in the past.1

This relational struggle between art and academia is not new, of course. In Antiquity forms of madness and divine inspiration, called enthousiasmos, mania of phantasmata were considered as methods that gave poets privileged access to the world of the muses and original ideas. These Greek terms later evolved into the concept of genius, where Immanuel Kant famously made a clear distinction between the genius-driven methodlessness of the arts and the predictable and method-laden world of scientists.2

This is not the place to recount the history of ideas related to the semantic spectra that surround the notions of ‘madness’ and ‘method’, but we can explore how ‘versus’, ‘in’ an ‘though’, the words used to frame this event, can be considered as connectors that relate to different attitudes in artistic research that nowadays co-exist and operate along a spectral continuum.

The first attitude in artistic research focuses on ‘versus’ and a situation of radical and functional separation. It is a perspective where both the field of academia and the field of artistic action live in a state of splendid isolation and specialisation. From this romantic and Kantian point of view, artistic practice has immediate access to a privileged world of ideas and creation, and should stay far away from all terrains that have the word ‘logic’ in their denomination. A potential opening to artistic research is one where it is stated that: 1/ practice is research, 2/ that the arts produce specific kinds of knowledge that are qualitatively different from traditional activities in academia, 3/ that this knowledge is embodied in the artworks that are produced and that ultimately any infiltration of academic vocabularies or procedures would harm, endanger and violate this specific contribution to human understanding.

The second attitude in artistic research can be linked to the connectors ‘though’ and ‘in’. Whereas the previous orientation was a Kantian one, we could call this perspective, in line with the title of the conference, a Shakespearian attitude. It is again represented by a small word, a preposition this time: the concept of Practice as Research. When artists look in the mirror of academia, they see that their specific practical activities such as sketching, drawing, rehearsing can take on a new life within a research context and that more generic activities such as collecting, experimenting and conceptualizing have a close connection to activities that are deployed in academia. It can then be enriching to reflect on these connections in function of the development of artistic practices.

Taking the ‘in’ and ‘though’ a step further, we encounter a third familiar movement in artistic research where mirrors are turned into windows— windows that are not only used to look through, but also serve as access to extra- and transdisciplinary fields and to the exchange of ideas and processes. Here the researcher shows a keen interest in the connection between art and academia and values the eclectic relations with other research disciplines and the methods prevalent in those disciplines. By its generous openness, this movement is both vulnerable and full of potential. It is vulnerable because of the danger of one-sided domination of established research practices, and it is full of potential because of the refreshing energy that opening windows can bring.

By sketching this continuum of possibilities that connects art to research via a number of linguistic connectors, we end up with a view of an almost unlimited terrain that seems to be connected by only one element, one recipe for action that is specific to artistic research, namely that in artistic research the research is done through artistic practices. Artistic research methods need to include elements of practice, in the narrow or broad sense, in order to qualify as artistic research. But is this enough as a guide for the future of artistic research? And how does this state of abundance relate to a second topic of interest that speaks loudly from the text you find in the flyer and is embedded in the following sentence: “it is very useful to take a closer look at and interpret the methodological bottlenecks for artists-as-researchers from a pedagogical point of view.”

I wondered what these bottlenecks at a pedagogical level could be and if one of them could be related to a state of affairs where, at least on a methodological level, almost anything seems to go. A situation which is quite challenging and very difficult to navigate. This so-called methodological pluralism or eclecticism presents itself indeed as an open but at the same time daunting place with hardly any points of reference.

In the Facebook version of the announcement for this event I noticed a separation between ‘method-’ and ‘-ology’ by a slash, suggesting that ‘method’ and ‘logos’ do not need to be intrinsically linked. In the foreword of the English version of Mille plateaux by Deleuze and Guattari, Brian Massumi summarizes some of the authors’ thoughts on the difference between ‘logos’ and ‘nomos’: “Nomad space is ‘smooth,’ or open-ended. One can rise up at any point and move to any other. Its mode of distribution is the nomos: arraying oneself in an open space […], as opposed to the logos of entrenching oneself in a closed space.”3

It is an idea that would require further investigation and substantiation, but a case could be made that artistic research is related to a state of ‘methodonomy’ rather than ‘methodology’: An open space where no particular boundaries or limitations are set, besides a central place for artistic practice, and where one has to set out an individual and tailormade trajectory in close relation to particular research questions or interests, over and over again.

Massumi further connects the space of the nomos to the one of air, whereas the logos is related to the space of earth. But again, the question prompts itself: how to behave or array oneself in such an open space, starting anew over and over again with the danger of losing track or getting lost?

I relate this question to Immanuel Kant’s remark in the Critique of Pure Reason: “The light dove, in free flight cutting through the air the resistance of which it feels, could get the idea that it could do even better in airless space.”4 We do not act in a complete vacuum, I think, given the centrality of practice, but this image suggests that some kind of resistance or order is needed to support and allow for free and creative flights. Paulo de Assis and Falk Hübner have both proposed such frameworks with specific attention for elements of emergence; their ideas can be consulted in the article that opens the thematic issue on methodology in FORUM+.5 But I would like to add here another option, one that keeps with the notion of a methodonomy, i.e. an open space, but also indicates ‘topoi’, a term borrowed from ancient rhetoric studies, here understood as strategic and fertile places in a methodical landscape that do not limit any terrain but are by their nourishing qualities frequently visited by artist-researchers.

A first topos focuses on creation and experimentation. Within this topos, artist-researchers enrich the field of artistic practice by focusing on the production of new artifacts or events. It is an action-based, hands-on topos that is closely and implicitly connected to the experimental and creative habitus of the artist-craftsman. This topos is concerned with the artistic material itself, which evolves into an artistic product by activities such as drawing, creative writing, composing, writing a film script, or developing a dance production or a performance.

A second topos, or frequently visited place in artistic research, does not focus on the product but rather on the artistic process and the tacit or embodied knowledge implicit in the creative act. It is the topos of reflection and can be related to the image of the mirror that we encountered in a previous phase of this text. Within this topos the intention is to scrutinize and verbalize through a process of self-reflection. Specific methods linked to reflection are activities such as thinking, imagining, conceptualizing, writing, modelling, developing, questioning, integrating, criticizing, articulating and reflecting-in-acting.

A third topos focuses on the exploration of new sources of information as a basis for further artistic reflection and experimentation. It prioritizes an outward look and explores the information galaxy for locating potentially relevant insights to then translate these into an artistic discourse and practice. It is the topos of the window or the bee, as stated by Francis Bacon in The New Organon: “it takes material from the flowers of the garden and the field; but it has the ability to convert and digest them.”6 Here, concrete actions on the level of method are reading, surveying, interviewing, collecting, asking, inquiring, observing, auditing, and so on.

The perspective of topoi is one that Aslaug Nyrnes advocates in an article dating from 2006, where she adds that artistic research is not about staying with one topos but about travelling in a space and as such connecting various outlooks and engagements with a field of interest.7 On this view, artistic research should always be about finding a balance between topoi; artistic research is research that combines experiment with reflection and information and in that manner moves beyond the private sphere of experience and creation. In a topical approach to artistic research, it is not about one topos versus the other but about connecting various strategic outlooks and engagements with regard to certain questions and interests in order to gain new insights.

The topical approach at the strategic level of artistic research, which is always open to additional topoi, is situated between openness and systematicity. It does not provide researchers or students with ready-made methods or a closed methodology but offers instruments to make up their own research design.

This balance between openness and systematicity brings me to the future of artistic research and its methodology, or methodonomy, as I would suggest to name what concerns us here.

It is often mentioned that artistic research is a young discipline, a qualification that implies that one day artistic research will naturally evolve into a mature discipline that teaches and disciplines its disciples with clear-cut paradigms and solutions. Is this the route we want to follow as a community of researchers? Or do we want to stay forever young? Or do we favour an in-between position, drawing on and sharing experiences in the field and being forever open to new and often rebellious perspectives by artists themselves. It is my view that artistic research has fruitfully weathered a first wave of discursive domination and disciplining. Whereas in its beginnings, the discourse was dominated by ontological questions formulated by theorists and specialists in philosophy and epistemology, we now see the emergence of a meta-practical discourse that is generated and owned by artist-researchers themselves and pragmatically supported by interesting practices.To me, at least, these are signals that we are slowly heading towards a balanced in-between situation where identity, freedom and constraint counterbalance and energize each other and sustain a longstanding youthfulness.

(…)

Notes

- 1 Henk Borgdorff, The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012), 37-39.

- 2 Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft (1790), §49.

- 3 Brian Massumi, foreword to A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), xiii.)

- 4 Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason. Trans. Paul Gruyer and Allen W. Wood. 15th printing (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 129.)

- 5 Falk Hübner and Joost Vanmaele, “Pathways to a Fertile Valley. On Methods and Methodologies in Artistic Research,” FORUM+ 27, no. 3 (Fall 2020): 4-16, https://www.forum-online.be/en/issues/herfst-2020/op-weg-naar-een-vruchtbare-vallei.

- 6 Francis Bacon, The New Organon, ed. Lisa Jardine and Michael Silverthorne (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 79.

- 7 Aslaug Nyrnes, “Lighting from the Side: Rhetoric and Artistic Research,” Sensuous Knowledge Journal 3 (2016).

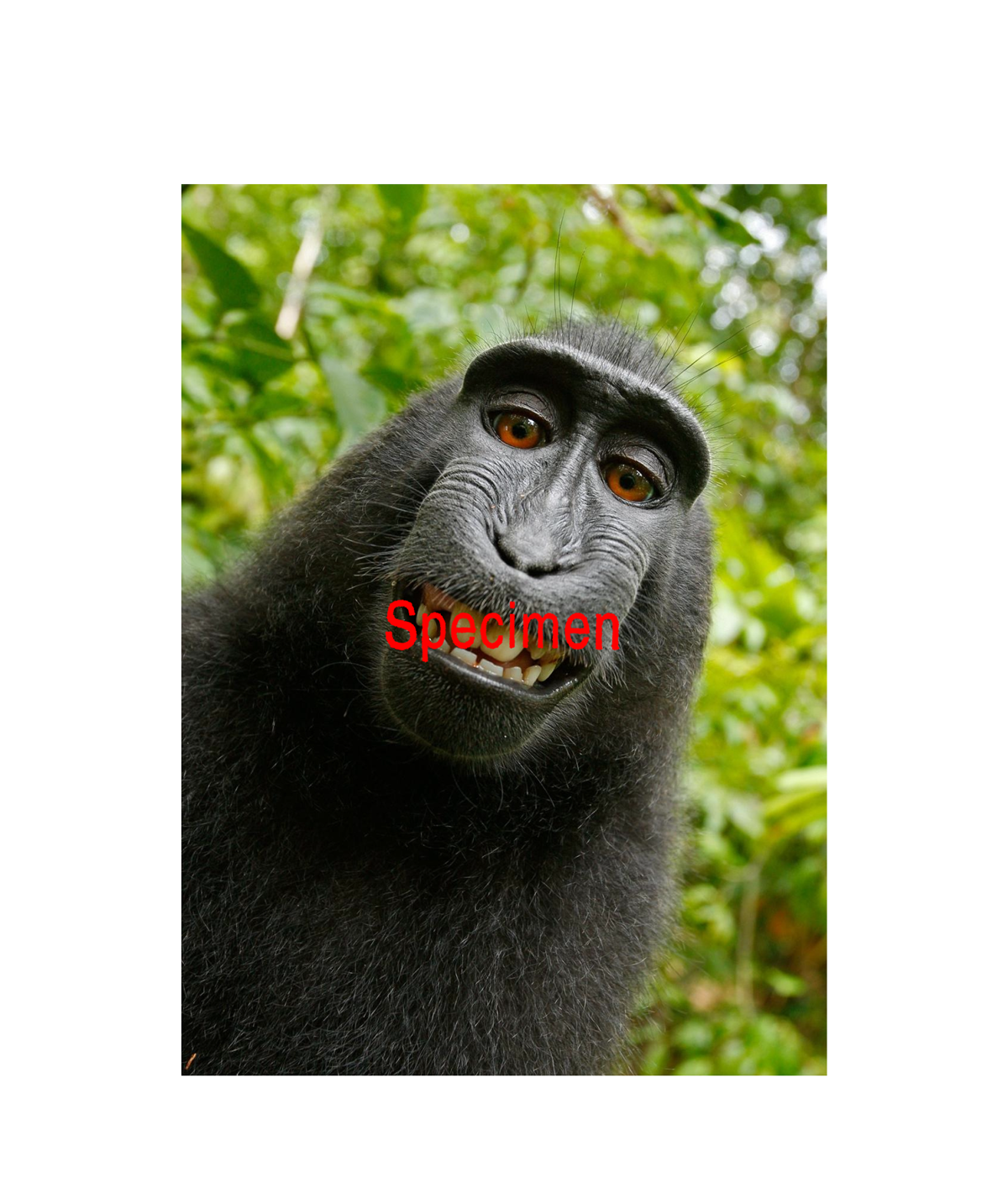

boundary thing 001652 (Monkey’s Selfies)

Agency

boundary thing 001652 (Monkey’s Selfies)

In 2011, David Slater, a wildlife photographer from the United Kingdom, traveled to Indonesia to take photos of the rare Sulawesi crested macaques. The crested macaques (Macaca nigra) are a species that today only lives in the Tangkoko Reserve, northeast of the Indonesian island Sulawesi (Celebes), and on smaller neighboring islands. Over the last 25 years the number of crested macaques has decreased by approximately 90%. The Tangkoko Reserve is near a village and the macaques are used to encountering tourists and photographers. During Slater’s visit, one macaque examined and manipulated his camera. When Slater retrieved his camera, there were several photographs taken by the macaque on it. In 2011 Slater published some of these photographs under the title Monkey’s Selfies. One photograph was included in The Daily Mail online newspaper. Its copyright notice read: “Copyright Caters News Service”. Monkey’s Selfies went viral on the internet. In November 2014 Slater published the Monkey’s Selfies series in the book Wildlife Personalities.

In 2015 Next Friends of Naruto, a group including People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), an animal rights organization from the United States, and Antje Engelhardt, a primatologist from Germany, filed a complaint against Slater for the violation of the macaque’s copyright by displaying, advertising, and selling copies of the photographs. Engelhardt studies the endangered Sulawesi crested macaques as part of the Macaca Nigra Project. She claimed that Naruto, a six year old macaque, took these photos. Next Friends stated that Naruto should have the right to own and benefit from the copyright of the photos in the same way as any other author would. They claimed that all benefits of Monkey’s Selfies should fund the conservation efforts for the Macaca nigra. Slater argued that PETA’s claim should be dismissed because animals such as Naruto are not protected by the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976.

On January 28, 2016, the court case Naruto v. David Slater took place at United States District Court of California. Judge William Orrick held:

I disagree with Next Friends. [...] Here, the Copyright Act does not “plainly” extend the concept of authorship or statutory standing to animals. To the contrary, there is no mention of animals anywhere in the Act. The Supreme Court and Ninth Circuit have repeatedly referred to “persons” or “human beings” when analyzing authorship under the Act. [...] “For copyright purposes, however, a work is copyrightable if copyrightability is claimed by the first human beings who compiled, selected, coordinated, and arranged [the work].”1 [...] Next Friends have not cited, and I have not found, a single case that expands the definition of authors to include animals. [...] Moreover, the Copyright Office agrees that works created by animals are not entitled to copyright protection. It directly addressed the issue of human authorship in the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices issued in December 2014 (Compendium). [...] [T]he Compendium states that, “[t]o qualify as a work of ‘authorship’ a work must be created by a human being. Works that do not satisfy this requirement are not copyrightable”.1 Specifically, the Copyright Office will not register works produced by “nature, animals, or plants” including, by specific example, a “photograph taken by a monkey”. [...] Naruto is not an “author” within the meaning of the Copyright Act. Next Friends argue that this result is “antithetical” to the “tremendous [public] interest in animal art”. Perhaps. But that is an argument that should be made to Congress and the President, not to me. The issue for me is whether Next Friends have demonstrated that the Copyright Act confers standing upon Naruto. In light of the plain language of the Copyright Act, past judicial interpretations of the Act’s authorship requirement, and guidance from the Copyright Office, they have not.

The court dismissed the complaint by the Next Friends of Naruto and concluded that photographs taken by a non-human are not protected as a work of art within the meaning of the Copyright Act.

Notes

Het lopend gesprek

Over de wandeling als blikwisseling

Katinka de Jonge

Toen de wereld tot stilstand kwam, begon ik te wandelen.

Dat klinkt dramatisch, en dat was het ook, want ik was bijlange niet de enige. In de lente van 2020 wandelde ik tussen drommen mensen langs de Scheldebocht, die alleen of in groepjes, met kinderwagens, picknickmanden, honden, stepjes en rolschaatsen, de smalle paden bevolkten.

We wandelden niet uit luxe maar uit noodzaak, het was de enige activiteit die een pauze gaf van het beeldscherm dat ons dagelijks achtervolgde. De enige manier om de wereld in perspectief te zien, en vanop een afstand onze nieuwe situatie van stilstand te observeren. Hoe waren we hier terechtgekomen? Ikzelf was nog maar net in deze stad komen wonen en mijn huis bevond zich op een prettig overgangspunt tussen het centrum en de velden erbuiten. Wandelen werd een ritueel dat deze twee werelden verbond.

Later schreef ik een voorstel om een artistiek buurtproject op te zetten, omdat ik de stad beter wilde leren kennen. Het was nog niet geheel duidelijk wat het resultaat zou zijn. Ik wist alleen dat ik weer wilde wandelen, en dat ik samen met buurtbewoners de voor mij anonieme straten, pleinen en parken een gezicht wilde geven. Binnen mijn artistiek werk bekijk ik publieke ruimte vanuit de spanning tussen het ontwerp enerzijds en het dagelijks gebruik anderzijds. Kan wandelen in die optiek een subversieve tactiek zijn?1 Met dit project wilde ik focussen op de relatie tussen de wandeling en het gesprek. Ik wilde onderzoeken hoe mensen, door samen te wandelen en te spreken, hun omgeving anders begrijpen.

Ruimten Rondom

As humans, walking defines us. We are two legged apes. We walk, and we talk. We are the thinking minds – thinking in language, more often than not. The rhythms of our walking and thinking are one.2

De titel ‘Ruimten Rondom’, naar het bekende boek van Perec, gebruikte ik aanvankelijk als werktitel, maar gaandeweg merkte ik dat deze titel toch mijn houvast werd, en dat de titel steeds meer betekenissen kreeg. In het boek omschrijft Perec de ruimte rondom zichzelf beginnend vanuit zijn eigen bed, en uitwaaierend in de wereld. In eerste instantie was mijn titel een verwijzing naar het boek zelf, een manier om de omgeving te omschrijven. ‘Ruimten Rondom’ impliceert ook een kern, een kern waar het níét over gaat, maar waar omheen wordt gecirkeld. Of zoals Perec het zelf omschrijft:

Het onderwerp (...) is niet precies de leegte, maar veeleer wat zich daaromheen of daarin bevindt. Om te beginnen is er dus niet veel: het niets, het onvatbare, het virtueel immateriële, de uitgebreidheid, het exterieure, datgene wat buiten ons is, datgene waar we ons middenin bewegen, het milieu waardoor we omgeven zijn, de ruimte om ons heen.3

Dit sloot perfect aan bij hoe ik wandelen was gaan bekijken. Wandelen als tussenruimte, tussen locatie a en b, als eeuwige omweg, als iets dat altijd veranderlijk is.

Wandelen is zichzelf veranderen

Wandelen is zichzelf veranderen. Zo staat te lezen in het Vroegmiddelnederlands woordenboek, (online te raadplegen als onderdeel van het Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal) dat de woordenschat van de dertiende eeuw verzamelt.4 Wandelen is wenden, wentelen, maar ook herhalen, heen en weer gaan. In latere eeuwen verbreedde de betekenis naar ‘rustig stappen voor het genot’. Doelloos rondwandelen was aanvankelijk een hobby van de Europese adel. In de achttiende en negentiende eeuw kregen stedelingen openbare parken en promenades, waar zij naar hartenlust konden slenteren, kletsen, flirten en anderen ontmoeten.

Over het fenomeen wandelen bestaat een heel discours met een traditie die teruggaat tot 1770 (al schreven de Oude Grieken ook al over wandelen om gezond te blijven).5 In 1770 schreef Jean-Jacques Rousseau voor het eerst over het fenomeen wandelen. Volgens Rousseau is wandelen een eenzame bezigheid. Tijdens zijn wandelingen voelde Rousseau zich vrij en onthecht genoeg om onbekommerd te denken en te mijmeren. Het zijn die alledaagse gedachten die de beste toegang geven tot wat en wie hij werkelijk is.6

De figuur van de flaneur (iemand die door in de stad te lopen de stad ervaart) wordt rond 1850 voor het eerst beschreven door Charles Baudelaire.7 Het flaneren was volgens hem de moderne levensvorm bij uitstek: de moderne mens (of ja, man) flaneert over drukbevolkte boulevards, langs de anonieme massa. De flaneur, die alles met een gepaste afstandelijkheid aanschouwt, wordt gezien als hét product van de moderniteit. Het wandelen door de stad speelt een belangrijke rol in het begrijpen, het deelnemen en het vastleggen van de stad. Waar Rousseau zichzelf afzondert tijdens zijn wandelingen, wil Baudelaire juist zoveel mogelijk communicatie en interactie met zijn omgeving uitlokken. De stad is een eerste vereiste voor de flaneur.

Geïnspireerd door o.a. Rousseau en Baudelaire ontstaat een eeuw later de groep van de Internationale Situationisten.8 Opgericht in 1958 streefden de Situationisten ernaar om een toestand van voortdurende maatschappelijke revolutie te creëren. Dit deden zij door het uitvoeren van ontregelende situaties en happenings. Hun zogenaamde dérive (afdrijven/afdwalen) is een variant op Baudelaires flaneren. Guy Debord beschrijft de dérive als het lopen in de stad zonder een specifieke bestemming, om zich zo opnieuw over te kunnen geven aan de prikkels van de omgeving en de daarmee gepaard gaande ontmoetingen. Het ronddolen zonder specifieke bestemming en jezelf opzettelijk proberen te verliezen in de stad zou een radicaal nieuwe ervaring van de stad mogelijk maken. Deze manier van wandelen was een spel, en een methode om de stad als ontregelend en inspirerend te ervaren, om anders te denken over de ons omringende ruimte.

De natuur van de stad

De spanning tussen wandelen in de natuur en in de stad is als een rode draad verweven door het project Ruimten Rondom. De artistieke organisatie die het project ondersteunt bevindt zich in een voormalige arbeidersbuurt aan de rand van de stad. Het is een dichtbevolkte volkswijk die deel uitmaakt van de negentiende-eeuwse industriële gordel, zoals veel grotere steden in België die kennen. En hoewel de buurt dus in dezelfde tijd werd gebouwd als de promenades en de parken voor de adel, kende deze arbeiderswijk geen open ruimte, laat staan groene ruimte. Er werd aanvankelijk überhaupt niet nagedacht over de leefbaarheid van de wijk. De grijze straten en karakteristieke cités bevonden zich onder de rook van twee grote fabrieken die werkkrachten nodig hadden om te kunnen draaien. Alle andere voorzieningen waren ondergeschikt. Arbeiders werden geacht om van de fabriek naar huis te wandelen, met hoogstens een omweg langs de kerk of de buurtwinkel. Vrouwen en kinderen werkten ook in de fabriek. Hoewel het dagelijks leven zich voor een groot deel op straat afspeelde, was dit eerder een onvermijdelijke expansie van de woonkamer van de klein behuisde gezinnen, dan dat het de bewoners toeliet om, zoals Rousseau het omschrijft, onbekommerd te denken.

Openbaar groen was er honderd jaar geleden nauwelijks te bekennen. Als je geluk had, had je een klein tuintje waar je wat groenten in kon kweken, maar daar hield het vaak wel op. Momenteel zijn er echter vrij veel parkjes en andere stukjes groen in de buurt, maar hoe waren deze er gekomen? Ik besloot op verkenning te gaan.

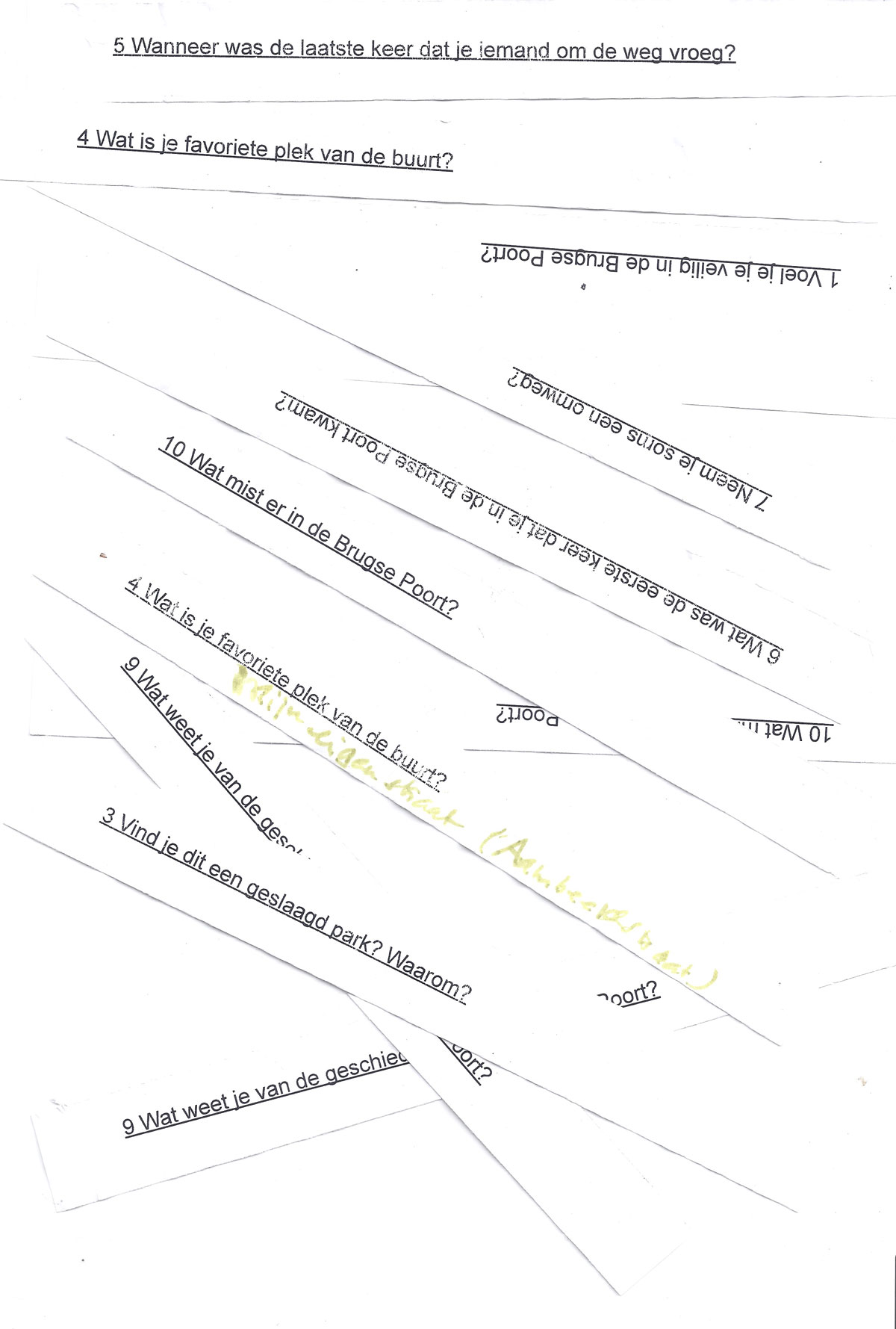

Het spel

Ik maakte een plan waarbij ik één keer per week zou gaan wandelen, en waarbij mensen uit de buurt zich konden opgeven om mij te vergezellen. Samen met telkens andere groepjes buurtbewoners vertrok ik altijd vanuit dezelfde locatie voor wandelingen van twee à drie uur, zonder vooropgesteld plan. Geïnspireerd door de situationistische dérives draaide ik de verwachte rollenpatronen om, en gaf de controle uit handen. Wie meewandelde kreeg een rol: gids, verslaggever of fotograaf. De wandelaars kenden elkaar vaak niet, en door een rol op te nemen en de bijbehorende attributen toebedeeld te krijgen, werd het ijs gebroken om in gesprek te gaan. Er ontstond een speelse sfeer zonder dat die opgelegd aanvoelde.

Ik leerde om niets voor te bereiden. Niet waar we naartoe zouden gaan, niet waarover we zouden spreken, niet waar we even stil zouden staan of wie of wat we zeker moesten tegenkomen, daar was het weer, de Ruimten Rondom, het toelaten van de leegte waarrond men zich beweegt. Er waren bewust twee gidsen, die met elkaar moesten overleggen over de route. Er waren twee verslaggevers, die ik een audiorecorder meegaf met het verzoek om gesprekken op te nemen. Vaak werd de aanwezigheid van de recorders na een tijd vergeten, waardoor de interviewachtige conversaties al gauw hun lossere en associatieve vorm terugkregen. Ik kocht voor elke wandeling een wegwerpcamera, waarmee de fotograaf mocht fotograferen wat die zelf belangrijk achtte.

Gezamenlijk wandelden we telkens door dezelfde straten van de buurt, en het viel op hoe traag wandelen gaat als je met een groep van ongeveer 10 personen bent. Er werd stilgestaan bij elke opvallende gevel, bij elke boom die niet in het rijtje paste, bij elke ongehoorzame geveltuin. In tegenstelling tot de eenzame mijmeringen van Rousseau werden mijn wandelingen een collectieve oefening in observeren. De straten werden telkens op een andere manier beschreven. Dezelfde verhalen werden door andere stemmen telkens op een andere manier verteld, en langzaamaan werd de groep een collectief brein dat de verhalen aanvulde en corrigeerde, of een nieuwe richting liet inslaan. De buurt werd nauwkeurig uitgepakt, en door de verschillende stemmen en perspectieven van de buurtbewoners werd dit voor mij een beeld in 4D.

De parken

Ik hield van de verhalen die de deelnemende wandelaars mij vertelden, en die uiteindelijk zoveel meer bleken te zijn dan louter anekdotes. De gesprekken lieten mij reflecteren over de verbondenheid van veel bewoners met hun omgeving. Door de recorders werden alle conversaties en interacties opgenomen en na een aantal wandelingen merkte ik dat veel verhalen cirkelden rond de tuinen en parken in de buurt. Dat was niet voor niets het geval. De aanvankelijk grijze buurt had geen groen. De oudere bewoners vertelden mij dat hier pas verandering in kwam toen een van de fabrieken in de jaren 60 van de twintigste eeuw failliet ging. De gebouwen werden gesloopt en het steenpuin bleef liggen, daarop groeide al snel een dicht bos. Plotseling was er een groene plek gekomen in de volgebouwde wijk. In de jaren 1970 leefde de vraag wat er met de open ruimte aan de rand van de wijk moest gebeuren. In eerste instantie leek het logisch om de hele plek vol te bouwen. De vroegere fabrieksgronden waren immers als bouwgrond bestemd. In die geest zijn destijds een aantal appartementsgebouwen opgetrokken, volledig volgens de ideeën van het Nieuwe Bouwen: een scheiding van functies, hoogbouw met groene grasvelden eromheen. De bedoeling was om hier nog eens vijf gelijkaardige blokken aan toe te voegen. Toen de aannemer failliet ging, werden die plannen opgeborgen en bleef het groen staan. Wat de beleidsmakers echter niet beseften, was dat de buurt al een functie voor deze ruimte had bedacht, en dat het groen al snel vergroeid was met het sociale weefsel van de buurt. Het deed mij denken aan wat Jane Jacobs in 1961 schreef in haar befaamde boek Death and Life of Great American Cities:

I will write mostly about general, ordinary things: for example, what kind of urban streets are safe and what kind are not; why some urban parks are beautiful and others are life-threatening ponds of lewdness; [...] what an urban neighborhood actually is and what tasks, if any, neighborhoods in big cities fulfill. In short, I will describe how cities function in real life, because this is the only way to find out which planning principles and which renewal practices can promote the social and economic vitality of cities, and which practices and principles weaken these qualities.9

Het braakliggend terrein was al lang geen lege ruimte meer, maar een plek om te wandelen, picknicken, te spelen en de hond uit te laten. Het enige wat het stadsbestuur moest doen, was hiernaar luisteren, en dit helpen faciliteren.

Maar dat deden ze niet meteen, dus roerde de buurt zich. In de jaren die volgden pleitten actiegroepen van buurtbewoners voor een groot park. Ze bezetten het terrein met een tentenkamp dat soms verschillende maanden bleef staan, ze bouwden boomhutten en organiseerden feesten. Dertig jaar lang volgden verschillende bouwplannen elkaar op, en telkens kwamen nieuwe actiegroepen op voor het behoud van hun ‘groene vallei’. Totdat, eind jaren 1990, eindelijk de knoop werd doorgehakt: het zou een park worden.

De strijd om groene ruimtes is nog altijd een humuslaag die de buurtbewoners verbindt. Nog altijd wordt één keer per jaar een groot feest georganiseerd in het park, en velen herinneren zich de bezettingen als de dag van gisteren.

Niet lang na deze overwinning stond er een nieuwe generatie op die, na het verzet van de jaren 1970, op een andere manier de strijd aanbond voor het behoud van hun buurt. Gentrificatie is het spook dat ook deze buurt eind jaren 1990 infecteerde. Doordat de buurt meer groen en andere voorzieningen kreeg, werd zij aantrekkelijker voor hoogopgeleide (witte) gezinnen, die de vervallen huisjes opkochten en opknapten. Cités werden platgegooid om er parken van te maken, en een aanzienlijk deel van de armere bevolking moest uitwijken. Als verzet hiertegen werden hele straten gekraakt om de plannen voor de toekomstige parken tegen te houden. Groen werd gezien als de gentrificatiemotor van de stad.

Mede door deze geschiedenis werden keer op keer de planten, plantsoenen, perkjes, bomen, geveltuinen en grasveldjes uitvoerig besproken tijdens de wandelingen. Wie maakt er gebruik van? Voor wie zijn de ruimtes toegankelijk en voor wie niet? Welke soorten planten en bomen groeien er, en wat groeit er maar hoort er niet te groeien? De blik op groene ruimte bleek de perfecte metafoor voor hetgeen wat wordt gedeeld, wat van iedereen is, en wat blijkbaar ook iedereen aangaat. Het onderwerp opende deuren om te spreken over andere zaken zoals de veiligheid op straat, discriminatie, toegankelijkheid en leefbaarheid. Onze wandelingen doorkruisten verschillende kennisgebieden, we hadden het over cultuur, antropologie, architectuur en stedenbouw, sociologie, onderwijs, biologie en filosofie. Het was onmogelijk om de gesprekken af te bakenen.

Lagen

Wat ik terugkreeg na al deze wandelingen waren urenlange geluidsopnames van buurtbewoners die even uit hun dagelijkse routine werden getrokken door een andere route te volgen, en zo de buurt van een andere kant bekeken. De woorden routine en route zijn niet voor niets met elkaar verbonden. Er ontstond ruimte om te reflecteren, om Rousseauiaans te mijmeren, Situationistisch te spelen, om te zoeken naar gedeelde grond.

Daarnaast kreeg ik een berg foto’s. De beeldenstroom vertelt ons iets over de blik waarmee verschillende bewoners hun eigen buurt observeren, en de esthetiek van de wegwerpcamera geeft een voyeuristische inkijk in een buurt die even specifiek als universeel is in haar identiteit en geschiedenis. De foto’s zijn aantrekkelijk doordat ze een zekere intimiteit en oprechtheid bezitten, het zijn ongefilterde beelden van de omgeving, de mensen en de sporen die zij achterlaten in hun buurt. Tegelijkertijd zijn de beelden herkenbaar en in zekere zin universeel: doordat elke buurt wel een bewoner kent die zijn geveltuin niet in toom kan houden, of dat ene huis dat werkelijk al drie jaar in de steigers staat, of dat basketbalpleintje waar alleen gevoetbald wordt, of die ene boom waar alle kinderen in klimmen.

Het mooie van het materiaal is de gelaagdheid ervan. Een moment wordt dikwijls driedubbel vastgelegd. Er is vaak niet alleen een moment in audio, maar er zijn ook de foto’s van de wegwerpcamera en foto’s genomen via een telefoon. Telkens als we dezelfde plek opnieuw bezoeken met andere wandelaars ontstaat er weer een ander moment, waarop een ander verhaal over de plek wordt verteld. De gelaagdheid die zo ontstaat geeft het materiaal een grote verbondenheid en verwevenheid, die meerstemmigheid toelaat. Door het materiaal opnieuw te bekijken ontstaan onverwachte verbanden en toevallige relaties die de buurt en de ervaring ervan op een heel dichte en subjectieve manier laten zien.

Fragment gesprek:

spreker 1 - Ahja wow spreker 2 - Een boom met krukken? Zit daar geen verhaal aan vast? spreker 3 - Die krijgt een uitkering nu… [gegiechel] spreker 4 - Ah daar, ja, daar had ik zelfs geen weet van, dat die ondersteund is spreker 1 - Ik heb dat ook nog nooit gezien, maar ik fiets hier gelijk… elke dag voorbij, da’s wel grappig… spreker 4 - Da’s ook een hele goeie klimboom spreker 4 - Waarschijnlijk daarom dat ie ondersteund is [gerommel, spreker 4 doet poging om in de boom te klimmen] spreker 1 - Moet ik u .. uhh – een voetje geven? spreker 4 - Wacht hé spreker 1 - 3, 2, 1 … spreker 2 - … en als je dan speelt en hij omvalt … spreker 1 - Ik ga je gewoon een voetje geven spreker 4 - Oke spreker 4 - Wacht he, die recorder [spreker 4 krijgt voetje van spreker 1 en klimt in de boom] spreker 1 - Ja, of om er makkelijker op te kunnen klimmen? spreker 2 - …. neee, dat denk ik niet, die balken, dat maakt het toch niet makkelijker? spreker 3 - Dat moet al een hele tijd zijn, he, dat ie ondersteund is, je ziet dat hem al dik ingegroeid is spreker 1 - Jajajjajaja – spreker 3 - En wat hebben ze hier zelfs gedaan, ze hebben gewoon hun riem ertussen gestoken - spreker 4 - Er zit hier een mega barst in de tak en er komt een eikje doorgegroeid spreker 1 - Komt er een eikje uit? spreker 3 - Groeit er een eikje door? spreker 4 - Ja, er groeit een klein eikje door de boom spreker 1 - Moet jij ook een voetje hebben? spreker 3 - Uuuh, ik denk dat het wel gaat lukken, ik moet gewoon even … wil je anders wel de camera vasthouden? spreker 1 - Dat kan ik – jaja [spreker 3 krijgt voetje van spreker 1 en klimt in de boom]

Uiteindelijk komen de beelden en verhalen samen in een publicatie. Ik heb lang over de juiste vorm nagedacht, maar weet nu dat ik het spel en het plezier van het wandelen zelf niet kwijt wil raken door de al te rigide vorm van een boek. Hierdoor besloot ik om alle beelden en geluidsfragmenten op een associatieve manier bij elkaar te brengen op losse kaarten. Op elke kaart staat een beeld, een omschrijving, een geluidsfragment in de vorm van een QR-code. Op de achterkant van de kaart staat de locatie van de foto aangeduid op een plan van de buurt. Op die manier kunnen de kaarten worden geschud, uitgekozen en gebruikt om een nieuwe route te bepalen. Het wordt zo een werk dat zichzelf telkens regenereert. De eerdere wandelingen bepalen de route van de volgende wandelingen, en tekens komt er een nieuwe laag van beleving bij. Door de vorm van losse kaarten is het mogelijk om verder te associëren door combinaties te maken, maar ook om nieuwe kaarten toe te voegen, en zo de mogelijkheden uit te breiden.

Door dit project ben ik mij anders gaan verhouden tegenover wandelen en routines, er gaat een bepaalde verfrissing vanuit om uit je dagelijkse routine te worden getrokken doordat iemand anders je route bepaalt. Ik hoop het ronddolen, flaneren, de wanderlust en de dérive terug te geven aan de buurtbewoners. Uiteraard zijn de huidige buurtbewoners andere mensen dan de arbeiders van honderd jaar geleden, maar de blikwisseling die wij creëerden, en de tussenruimten die wij bewandelden zijn iets wat mensen intergenerationeel met elkaar verbindt.

Noten

- 1 Michel de Certeau’s Practice of Everyday Life (California: University of California Press, 1980) is hierbij nooit ver weg. In het invloedrijke hoofdstuk “Walking in the City” stelt De Certeau dat “de stad” wordt gegenereerd door de strategieën van regeringen, bedrijven en andere institutionele instanties die instrumenten zoals kaarten produceren die de stad als een organisch geheel beschrijven. De kaart is vrijwel altijd een verticaal perspectief. Daarentegen beweegt de wandelaar op straatniveau zich op een tactische manier en nooit volledig bepaald door de plannen van organiserende instanties. Hij neemt bijvoorbeeld kortere wegen en ontwijkt daarmee het strategische raster van de straten. Dit concretiseert het argument van De Certeau dat het dagelijks leven zich afspeelt als een proces van het bewandelen van het grondgebied ontworpen door anderen, waarbij de patronen, regels en systemen die al bestaan, worden gebruikt op een manier die nooit volledig wordt bepaald van bovenaf.

- 2 Kerry Andrews, Wanderers. A History of Women Walking, (London: Reaktion Books, 2020)

- 3 George Perec, Ruimten Rondom (originele uitgave Fr. Espèces d’espaces, 1974), (Amsterdam: Arbeiderspers, 2008)

- 4 Vroegmiddelnederlands woordenboek, https://gtb.ivdnt.org/search/?owner=VMNW, geraadpleegd op 10-01-2022.

- 5 Aulus Cornelius Celsus, De Geneeskunst (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Damon, 2017).

- 6 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Overpeinzingen van een eenzame wandelaar (Utrecht: Uitgeverij Veen, 1994, eerst gepubliceerd in 1782).

- 7 Charles Beaudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life (London and NY: Phaidon Press, 1995, eerst gepubliceerd in 1863).

- 8 Andrew Hussey, Guy Debord. La société du spectacle et son heritage punk (Paris: Uitgeverij Globe, L’école des loisirs, 2014)

- 9 Jane Jacobs, Death and Life of Great American Cities, (NYC: Vintage Books ed, 1992, eerst gepubliceerd in 1961)

Strategy Guide for Environments

Amber Vanluffelen

A platform as displayed here: “A court, an area, a space, the gate, where I can dwell, explore, play, search, land, to end, to open and to discover, this cover is just another environment I hover over.” Well, that doesn’t seem to be entirely true. See, a shatter of it hit me in my area so ignorant of what I could possibly partake in. Completely immersed in aspiration, I fantasized about: You make very precise choices, when piercing through, the better the cut, the better the fit, might that be Balenciaga, Kansai, who cares? I carry.

Well, Land, The environment, The almighty has spun layers of atmosphere, even beyond the exosphere, into bindings of scriptures and scrolls; unrolling, all that lies latent within us, unveiling, upcoming, an extension of her belonging.

I believe these matters can be rendered through many things, such as: tokens, portable icons, cards, sports relics, sacred artifacts, all of them waiting to be evoked. Keep it closed and sealed, it will rest in its possibility to be anything, have any value, but might it be that its real value only comes through when taking matter into your hands when taking off its sacred seal when taking the cards in your hands, and let them strike, may they hit where the heart fits! Speaking about the latter, like I always say: Love, play, and conduct your game and manifest whatever it is you hold in your heart. Here, now, something is casting its shadow over the landscape. Let it also cast a spell, for it will enlighten us with its essence.

THE ORACLE

as disclaimer

She will generate all, she makes her words come into being; spell into life She will twist her tongue until no tale remains untold For she will speak in any language of enemy and ally She will facilitate the mayhem of your time She ought to turn and you continue She ought to repress herself until the day the ignoble regime has been turned over Into you For you will lift your spirits For she will grant you forgiveness And nothing will be forgotten Every effort, even the trembling of the spine of a leaf You might exhaust it all Still, her plains stretched at your sight, you regard them no longer But turn to the view of infinite suns Burning spear, piercing through all the bigger sphere Whenever you extinguish. Your ashes onto the earth For All, I will give you ground, on which you can rise Until the last has been generated I will gyre around you, demise you You might make moves of opposition and expose yourselves However, in any endeavor I trust that the nature you find Is my constellation, aligned and assigned to the words: “No one can deliver from thy hands” Then finally “I land and see“ “I land and see” All seems to fall on her surface now In place, because, anywhere is where she wields the parting glass Until her brightness deems the sever undone

A witness of the oracle: And there it is: no journey for me to embark on and mark, oh, solely by my theory. It seems; this environment, it is a force field in which we can maneuver; it gives rise to events strung together by time. It is there where plains and players reside in suspense, sparking depictions of their own dynamics into life. The very subject that will let you in, is the one you feel for Take it to heart and in the rotation of the chrono, the parting glass might just bring out the better passes, we call dimes

THE FORCE FIELD

This force field is constituted by some basic principles:

- Creating a court/ platform/ battlefield - Expanding and transcending borders

- Seeking to generate energy, giving life - Learning what’s close to one’s heart - Exchanging between realities - Generating its nature

Extract from Beigoma the movie, 2020

- Venturing with other players - Referencing spiritual realms

Hi, I’ve been sensing you for some time I like to feel you when your leaves lie low (I like to watch you really closely) The Tree is dimming the schemes of the grass no drone could catch what we No passenger other than me will fetch What we shattered, I really like how you host me This charm and chant you are unveiling my hand, exposing all that lies latent, a cover, forever able to discover its most valuable inside, I will not let it slip through my fingers I know I am not a fleeting illusion, your essence speaks to mine, letting me know I can unroll my soil and give life, unstoppable you wrinkling pool, touching my edges rejuvenating my senses Hosted by every ripple you cause at me Your spirit lies in every endeavor I can chop off a piece of wood and adore it Eventually, trespassing the root And I have left you, but the certainty of Your presence will stay in me When I land and see you, pool glaring in my eyes Surrounded by your proxies of divine dwellings Deeper and deeper, I understand I had to come My chest exposed to the fiercest strain, the sun we will be done, whenever, wherever, we roam; the sun, shines, glaring, my eyes, glancing, my mind, gone, we roam

Park walk Hymn, Mutoko: Mathias MU & Amber Vanluffelen, 2021

b

clustered | unclusteredEmbodied Knowledge

Thomas Moore, Agency, Ode de Kort, Florian Dombois

Movement operates from the middle of things.

— Bojana Cvejic, “How open are you open? Pre-sentiments, pre-conceptions, pro-jections,” in Sarma (October 2004).

Conductor as Subject.

An analysis of Alexander Khubeev’s Ghost of Dystopia (2014, rev. 2019)

Thomas R. Moore

Introduction

“Khubeev’s work is as much spectacle as musical experience; in this piece, conductor Thomas Moore was chained to the podium, his gestures the result of attempts both to gain musical control and break free. Though Khubeev’s training is rooted in electronics, the sounds here were largely acoustic. But what sounds! The eight-piece, string-heavy ensemble creaked back and forth like a piece of rusty machinery on its last legs: an ugly but utterly compelling piece of musical grunge.” (Reynolds, 2016)1

Reynold’s review serves as an unambiguous introduction to Alexander Khubeev’s (°1984) Ghost of Dystopia for ensemble and solo-conductor. The conductor, standing at the center, bound hand and foot to Khubeev’s self-made instrument, employs generally recognizable conducting gestures that generate the ‘grungy’ multiphonics. The instrument is a delicate web of glass, twine, and ‘acoustic sensors’2 that focuses the audience’s attention on the role of the conductor as the subject of the piece. In this paper I will first explore Khubeev’s score and self-developed gestural notation for the solo-conductor. I will then explain my analysis of the conductor’s shifting role from chained soloist to brutal dictator and its dystopic development throughout the piece. Lastly, I will detail detectable artistic and socio-economic motivations for utilizing a conductor in Ghost of Dystopia.

Specifics of the piece

— Alexander Khubeev (b. 1984): Ghost of Dystopia, written in 2014, revised in 2015 & 2019

— The 2015 revised edition was premiered during the Gaudeamus Muziekweek in Utrecht, The Netherlands. The 2019 revised edition was premiered during Klara Festival in Brussels, Belgium. Both were performed by Nadar Ensemble and Thomas R. Moore, conductor.

— Orchestration (2015): flute, clarinet, piano, percussion, violin, viola, cello, double bass, and conductor with acoustic sensors.

— Orchestration (2019): flute, clarinet, piano, percussion, guitar, violin, cello, and ‘conductor’ with acoustic sensors.3

Reading the score

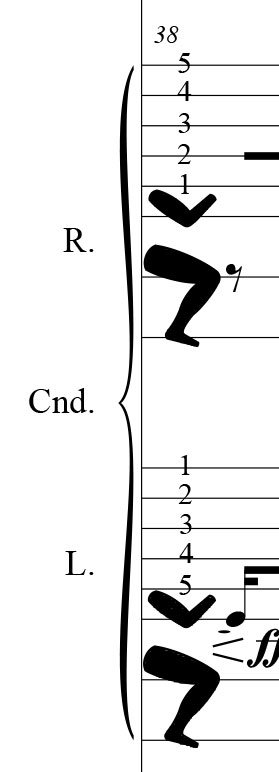

Alexander Khubeev developed a new instrument for Ghost of Dystopia that resembles a spider’s web made up of sixteen ‘acoustic sensors’. A conductor-like-figure4 stands at the center of this web and is bound hand and foot to sixteen plastic boxes of various shapes and densities. These boxes, with the open end facing downward, scrape along eight glass panels (two boxes per panel), pull hem and haw by the conductor’s gestures and generate unique multiphonic sounds. In the legend prefacing the score, Khubeev has indicated the general tuning of the sensors and their placement on the glass. The lower sounding boxes are attached to the ankles. The middle range is fixed to the knees and elbows and the higher boxes are bound to the conductor’s fingers.

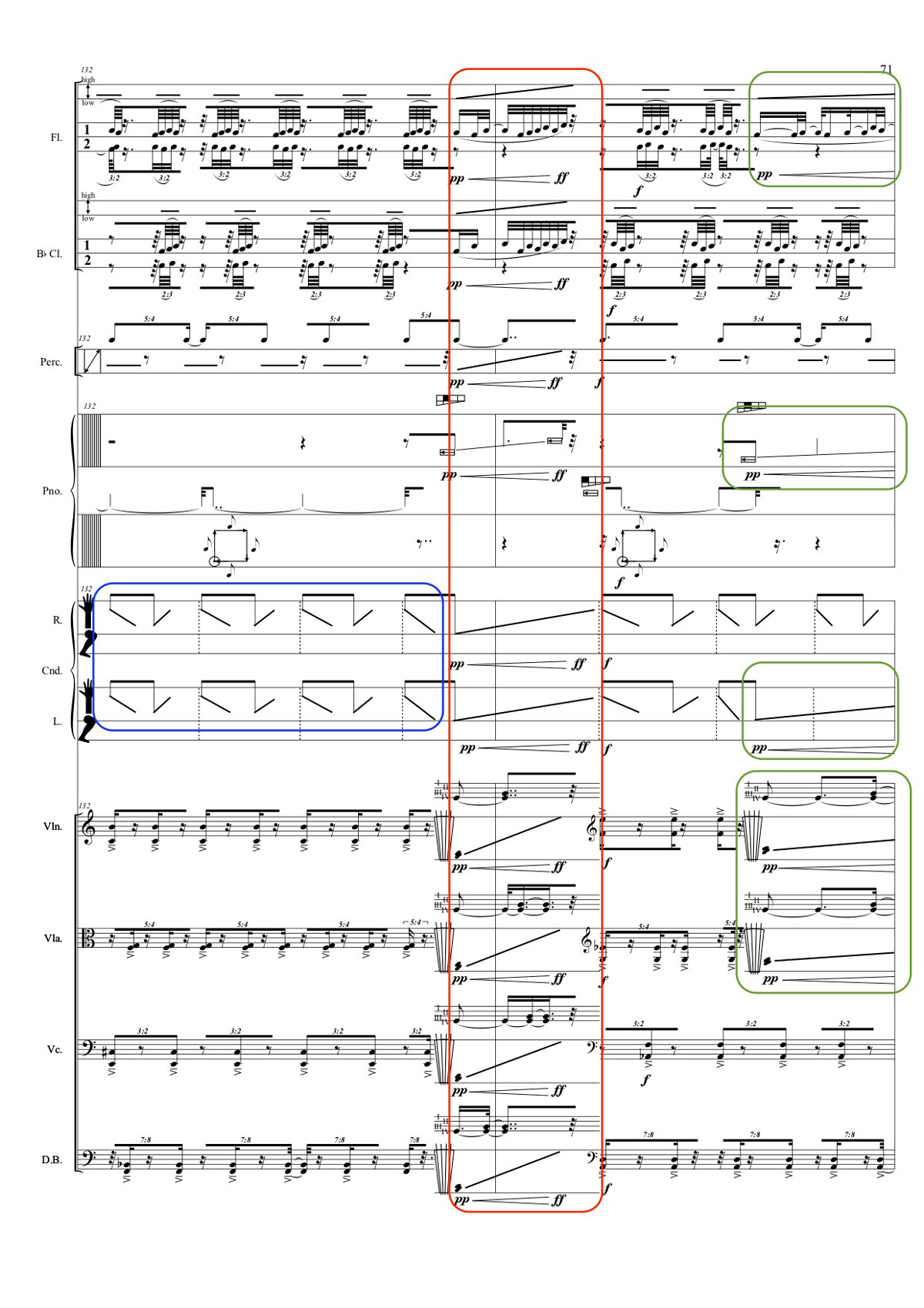

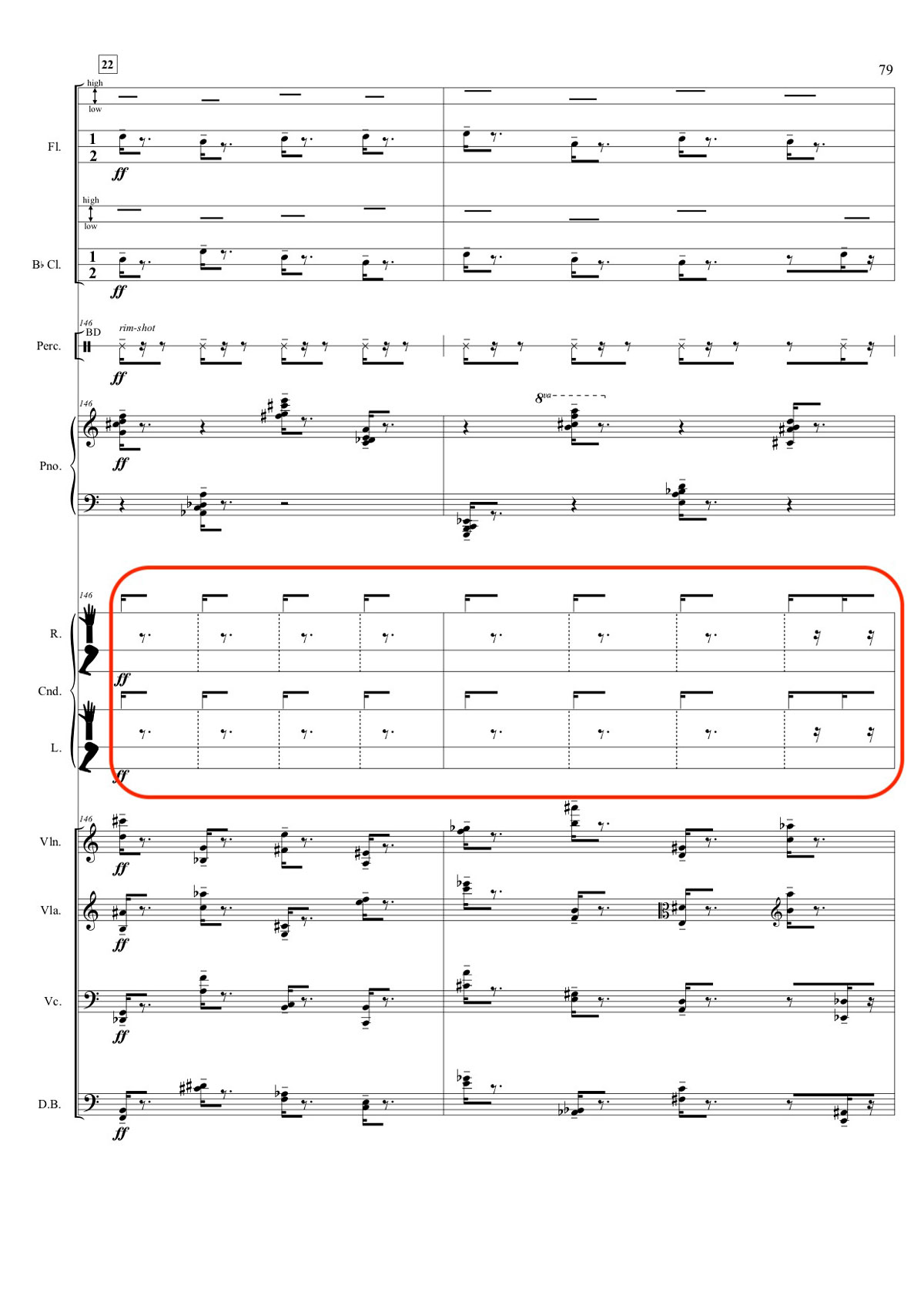

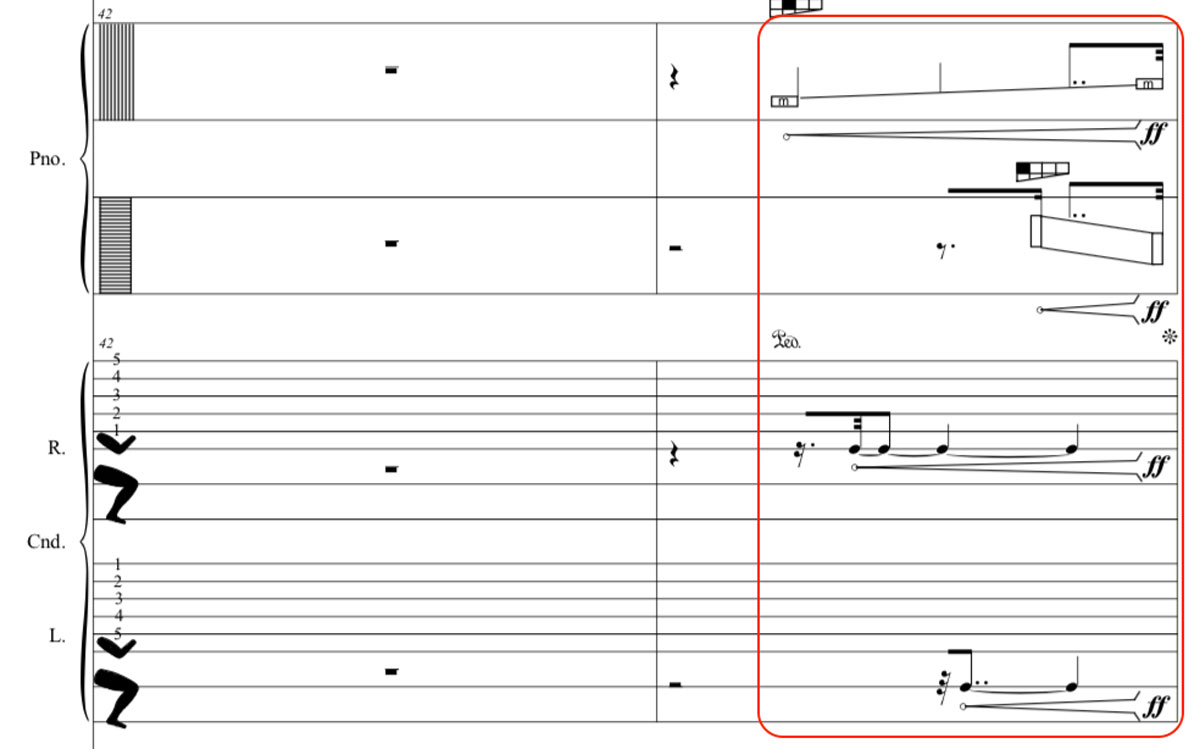

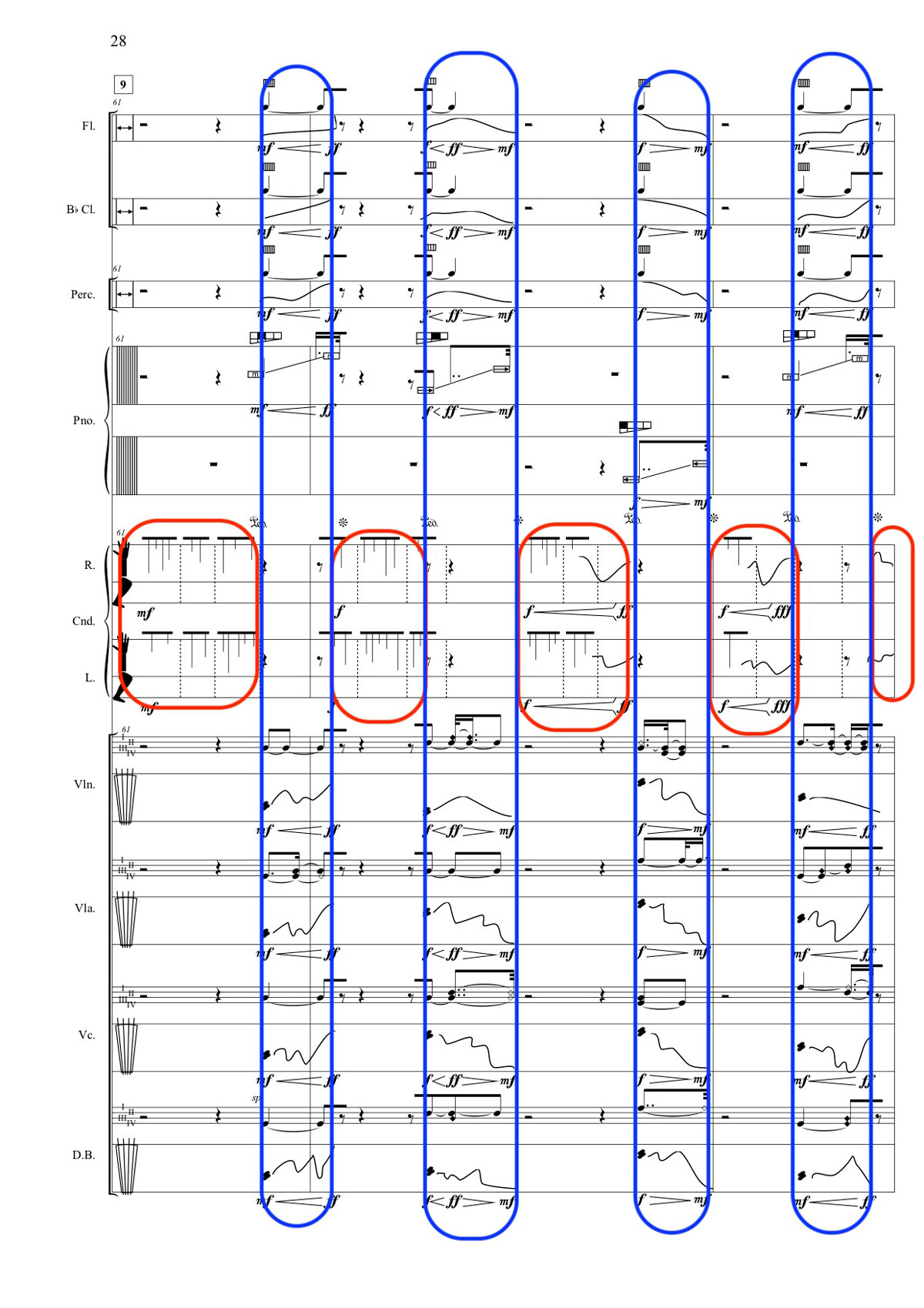

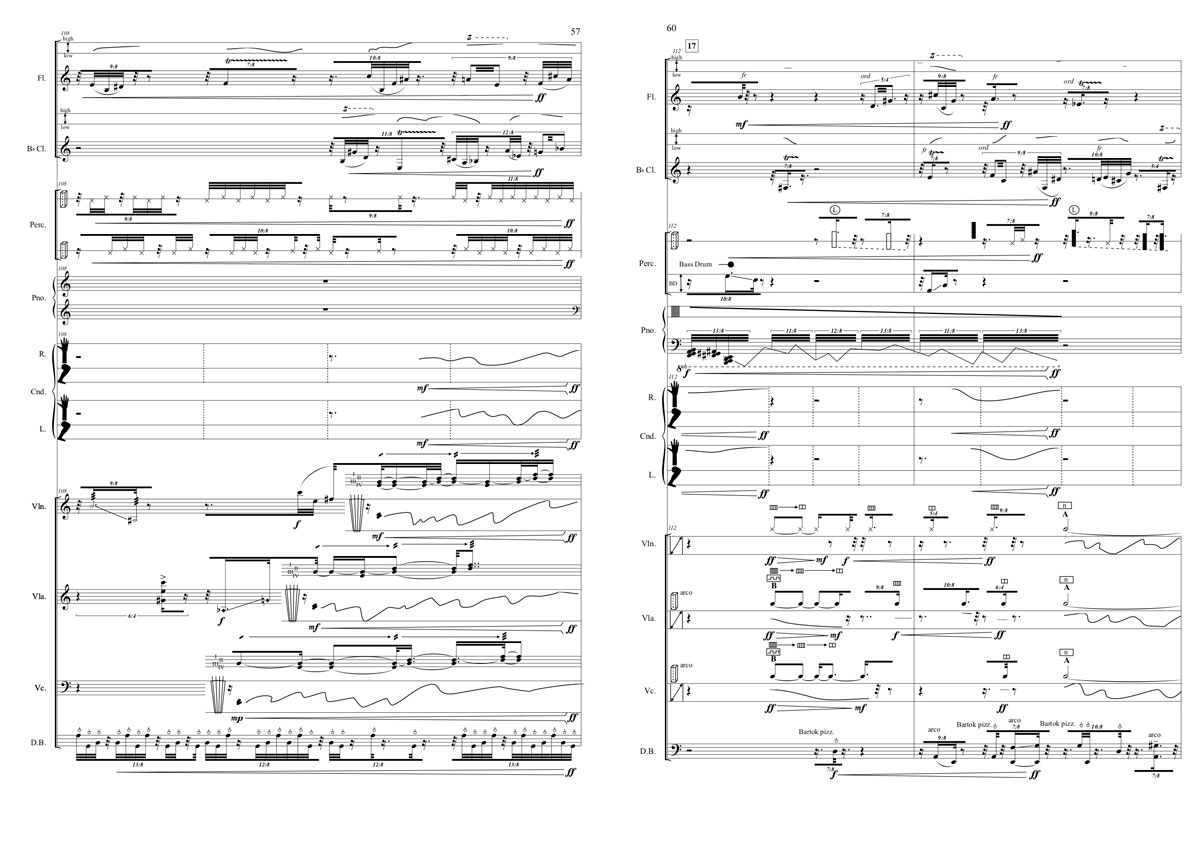

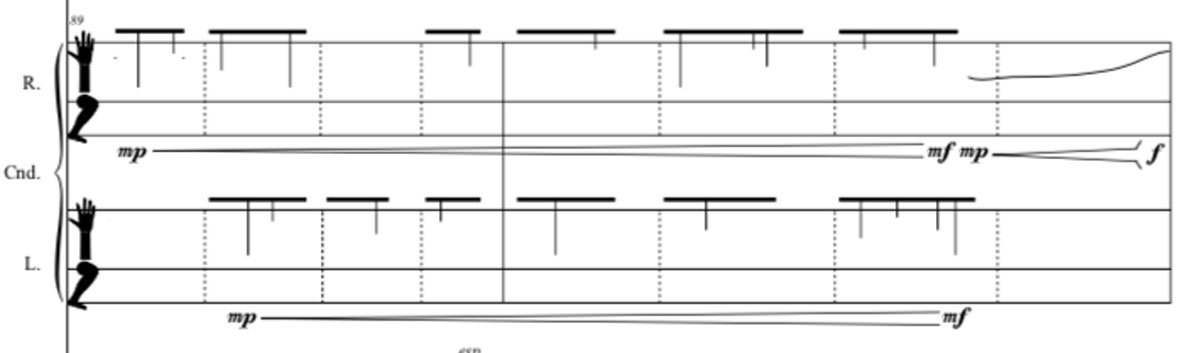

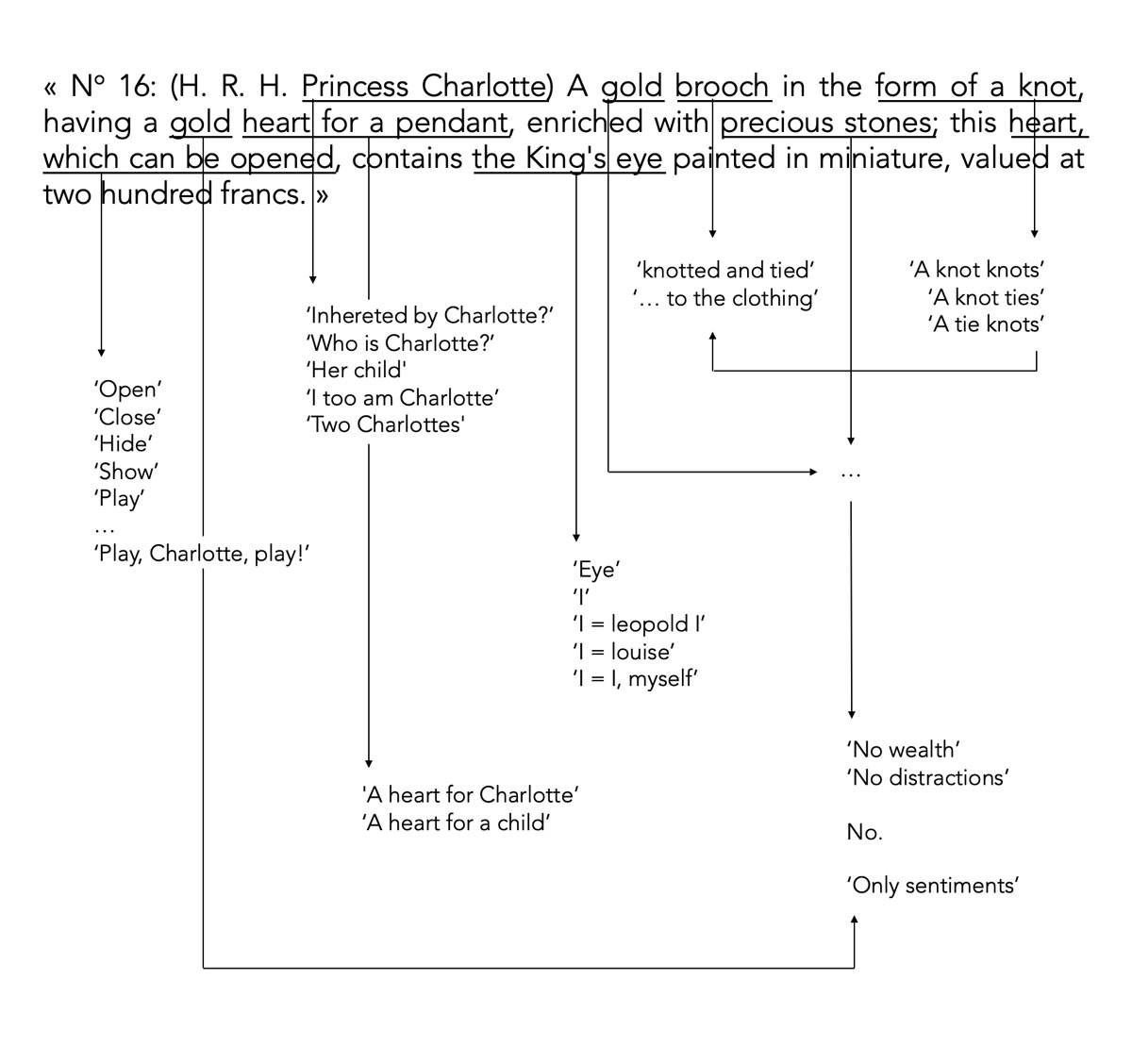

Khubeev developed a specific notation for the conductor’s movements (see figure 1). It has two staves and has been written into the score above the strings and below the piano and percussion parts. The upper stave is for the right side of the body and the lower for the left side. Like a percussion part, no traditional clef symbol is used. Instead, Khubeev has marked the beginning of each stave and system with elbow and knee symbols; above the elbow symbols are five additional lines that correspond with the five fingers on each hand. In total there are six lines per side for the arms and hands and two per side for the knees and ankles. The piece begins in this manner and continues so until the end of measure 56. From measure 57 until the end, the conductor’s score delineates combined movements for the upper body (fingers, hands, and elbows) while keeping the movements for lower body (knees and ankles) independent.

The conductor’s movements have been severely restricted by the composer. Any extra movements, such as turning a page in a score, would generate excess sound from the acoustic sensors. Therefore, out of practical necessity, the conductor’s part is displayed on a video monitor and shown in the form of a video score. A click-track, audible to all musicians via headphones, is synchronized with the conductor’s video score. This ensures that the pages are automatically turned at the correct moment and assists the ensemble with temporally synchronizing their performance. Here the dystopic duality of the conductor’s role in this work becomes apparent. By chaining the conductor, the composer ensures that every movement is audible, punishing any surplus in the harshest of screeching fashions. And yet, conducting is a movement-based musical practice. Musicians and audiences alike expect specific gestures5 from a ‘silent’ conductor6 that facilitate a musical performance in everything from entrances to temporal synchronicity. Both the click-track and especially the chaining instrument strip Khubeev’s conductor of their silence and a great deal of their facilitating functionality.

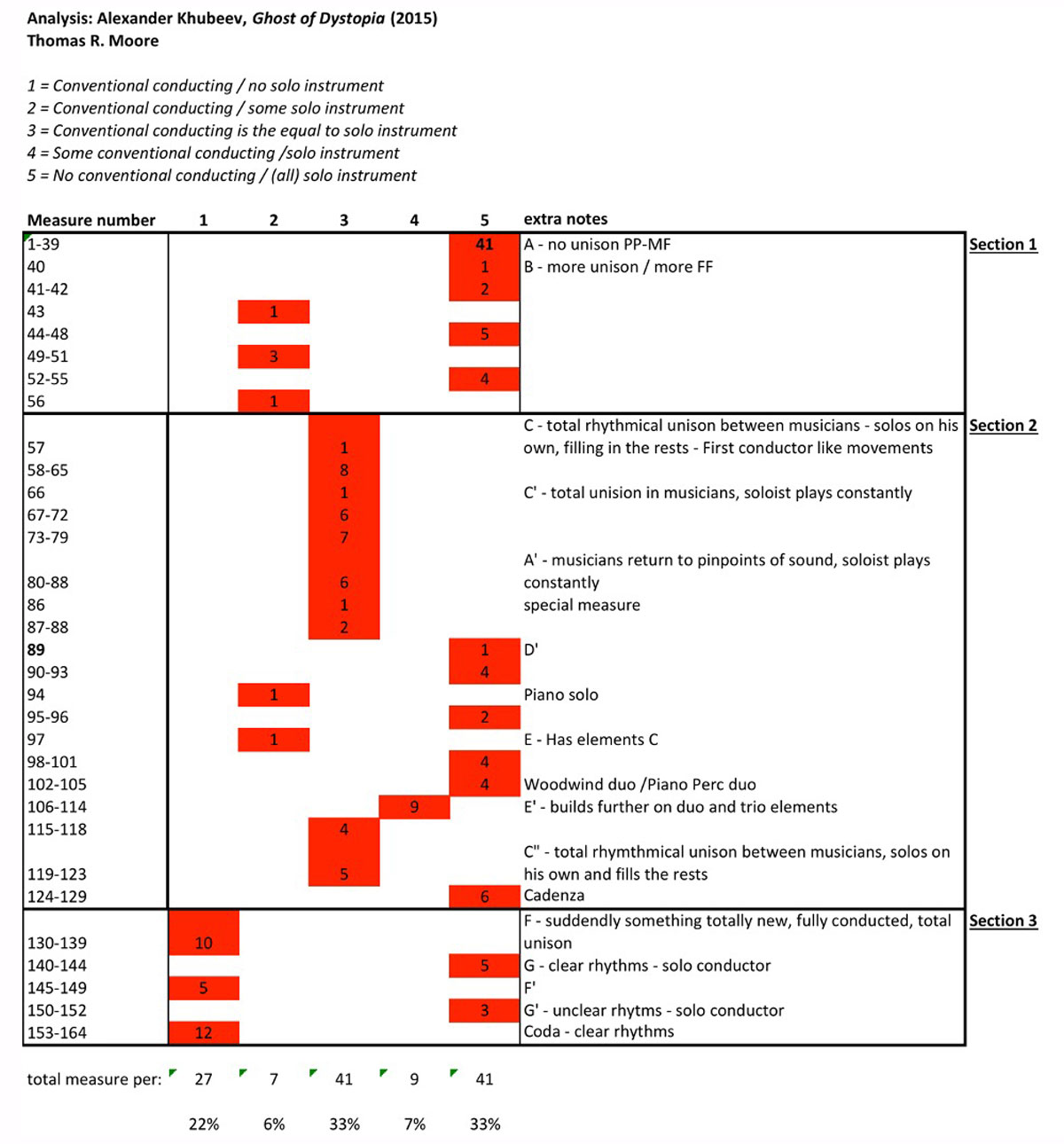

Analysis Method

Similar to my analysis of Alexander Schubert’s Point Ones (2012),7 I was able to divide the conductor’s role in Ghost of Dystopia throughout the piece into two polar functions: a soloist’s role and the more traditional post as ensemble conductor. There are measures in the piece when the conductor is completely focused on the ensemble, conducting every detail and showing every beat. There are also measures when he/she acts entirely as a soloist. Also, but only sparingly, he/she takes on both roles simultaneously and conjunctly. When simultaneous, the balance between the two roles is sometimes, but not always, equal, either leaning more towards soloist than conductor or vice versa.

To better understand and visualize this, I created a chart assigning each of the five above-described situations with a number. I used the number ‘one’ to represent a conventional conductor-ensemble relationship. The number ‘five’ represents the times at which the conductor acts as a soloist. The numbers in-between (‘two’, ‘three’, and ‘four’) are used to represent the parts in the piece when the conductor is both soloist and conventional conductor, with ‘two’ leaning more towards acting as conventional conductor, ‘four’ representing more of a soloist, and ‘three’ equaling balancing the two roles. The entire chart can be found in the appendix.

I will first describe each of the categories and where they can be found in the piece. Then I will apply the analysis and detail the results in terms of structure and measurable trends.

Category 1. Strictly conventional conducting

Khubeev waits until the final third of his piece to offer the audience, the musicians, and the conductor-soloist the chance to experience functional conducting gestures that are clearly linked to the material performed by the fellow performers on stage. In measures 130-139, the conductor is instructed to display a dry, dictatorial (even harsh) two-beat pattern. At regular intervals the conductor must also use his/her left and right hand to indicate a combination of glissando and crescendo by moving an open palm, arm extended, from low to high. This corresponds in a stereo fashion with the ensemble: Left hand = left side of the ensemble and Right hand = Right side of the ensemble. As shown in the example below, the choreographed (physical) gestures have a direct correlation with the musicians’ parts (see figure 2).

In measures 145-149, the conductor’s movements are also clearly linked with the musicians’ material. However, this time Khubeev has choreographed non-conventional conducting. The conductor improvises full arm, clock-like gestures that coincide with the rhythms in the musicians’ parts, utilizing minimum gesture for maximum effect from the ensemble. These measures can be viewed by clicking on the following link: https://youtu.be/fpPTaMCQ3YY?t=599

In the final twelve measures of the piece (m. 153-164), the conductor’s role verges upon the ritualistic. As the piece ends, the conductor raises his/her arms – starting very low, until they are pointed up towards the ceiling and extended in an open, Christ-like gesture. His/her movements correlate with a long crescendo in the musicians’ parts, bringing the ensemble’s role in the piece to a close and at the same time displaying the conductor’s freedom from the plastic box and glass plate instrument. During an interview, Khubeev indicated that these gestures are intended to create a kind of doubt over the fate of this newly arisen conductor-come-dictator.8

<5 class="secondsubtitle">Category 2. Mostly conductor combined with occasional responsibilities as instrumentalistOn rare occasions (6% of the piece), the conductor in Ghost of Dystopia combines fully conducting the ensemble with just a small amount of focus on the solo instrument. This is mostly because, by being bound to the instrument, the conductor’s conventional freedom of gesture has been severely limited. To find sections in the piece that fall into this category, I first had to look for places in which the sound generated by the conductor’s movements is a secondary effect of conducting-like gestures. The first example occurs in measure 43. The conductor has a crescendo both in the right elbow and the left knee that ends with an accent at the last possible moment in the measure. The piano has the same effect in both hands. Conventionally speaking, the pianist will look to the conductor to precisely time his/her accents.9

A similar situation occurs in measure 56. The conductor has a crescendo indicated in the left hand that ends with an accent at the last possible moment of the second beat of the measure. This coincides with the strings’ parts.

In measure 94, the conductor combines both non-functional conducting (solo) with a small movement at the end of the second beat that could be viewed as conventional conducting. With his/her entire left hand, the conductor moves rapidly to create a crescendo to forte and then abruptly stops with an accent at the last possible moment in the second beat. The flute, bass clarinet, and percussionist have exactly the same (timed) accent. In a similar fashion to the two examples cited above, the conductor’s movements could be considered to assist and unify the musicians’ parts.

Category 3. An even division of tasks: instrumentalist and conductor

In measure 57, the notation of the conductor’s part shifts from two eight-line staves to two three-line staves. Khubeev now writes for the hands in general (all five fingers and elbows acting in unison) and uses separate graphic notational lines for the acoustic sensors connected to the knees and ankles. (In total three lines: hands, knees, and ankles) The switch in notation coincides with two other events in Ghost of Dystopia. This is the first time during the piece when the conductor is equally both soloist and conventional conductor. It is also the first time we see the composer-choreographed use of recognizable conducting gestures in each hand.

Starting in measure 57 and continuing until measure 66, the entire ensemble, except the conductor, plays dynamically and rhythmically in unison. The conductor fills in the gaps, suffusing every rest that the ensemble has with a multiphonic reply. The gestures for the conductor are as follows:

During the conductor’s rests: freeze, highlight the ensemble (hands open, in front making a displaying/featuring gesture.)

During the conductor’s playing: make sharp down and up movements. (recognizable conducting gestures: ‘up’ and ‘down’ beats)

A second example can be found when the conductor makes a visible and audible (all the conductor’s movements are audible in this piece) decrescendo that begins in measure 73 and continues until the beginning of measure 79. The ensemble first makes an orchestrated (fewer and fewer musicians play) and then a performed (individual musicians decrease volume) decrescendo in the final measures. It could be argued that the conductor’s movements, like conventional gestures, guide the musicians from their loudest to their softest. His/her movements and the speed thereof also quite literally help to determine the collective volume of the piece.

Category 4. Mostly instrumental soloist combined with little actual or apparent conducting

It can be argued that thanks to performance rituals, any movement a conductor-like figure makes can be perceived by the audience (and the musicians, too) as a meaningful, and musically loaded gesture intended to influence the performance of the live musicians.10 Simply by standing in front of a group of classically trained musicians and in front of an audience who are attending a concert that takes place within the Western art music tradition, one could perceive the soloist in Ghost of Dystopia as a conductor. With that in mind, there are a few moments in this piece in which the solo-conductor is clearly acting in a solo role and his/her movements can also be interpreted as conventional and functional conducting gestures. Such an instance can be found in measures 106-114. The ensemble has been split into fixed duos (flute and clarinet, piano and percussion), a string trio (violin, viola, and cello) and another soloist (the double bass). The conductor-as-soloist regularly accompanies these groups. (See figure 7.)

Category 5. Completely and solely instrumental soloist

Ghost of Dystopia opens with miniscule sounds and physical gestures. These pianissimo events originate with the conductor and resonate throughout the entire ensemble. The sounds are sharp multiphonics generated by scraping plastic containers across glass plates and drawing well-rosined bows along the hard edges of plastic boxes. The conductor’s instrument is similar to the prepared conventional acoustic instruments present. A single (physical) gesture is directly linked to sound. One tug of the finger creates an audible plastic multiphonic. A raised (or lowered) arm creates a mass of sounds. All of this occurs in real time and can easily be perceived by a visually attentive audience: one movement equals one sound.

For the entire first section of the piece (measures 1-41), the conductor is clearly and solely focused on operating the instrument to which they are bound. The choreographed (physical) gestures found in the conductor’s score are written in a style similar to a percussion or piano part: each plastic box has its own line in the score (see the figures above). And, like all the other performers on stage, not a single note in these first 41 measures is played in unison with any other player. Besides the conductor’s physical position in the ensemble, there are at this point in the piece no other indications that the conductor’s physical gestures can be interpreted as anything other than instrumental. Thus, they are in no way conducting the ensemble.

This dedication to the instrument returns several times throughout the piece. I will examine three moments in particular. The first begins in measure 89 and continues for five measures. The conductor employs movements during these measures that can be described as non-functional conducting patterns. In other words, the audience can perceive the physical gestures that have been choreographed by the composer as movements a conductor might normally make in a conventional setting. However, the movements have no direct apparent correlation to the notes played by the other performing musicians.

As in Schubert’s Point Ones, an aesthetically similar piece for augmented conductor and ensemble, the conductor in Ghost of Dystopia is granted the opportunity to perform an exciting and dramatic cadenza, the second example of category five. However, instead of drawing the audience’s attention to the conductor’s grasp upon the live electronics, the solo in Ghost of Dystopia is quite literally liberating. If the solo cadenza is played with enough (and suggested by the composer)11 enthusiasm and wildness of (physical) gesture, the connections between the fingers and the acoustic sensors will snap. The goal of the conductor during the cadenza is to break the strings that bind him/her to the boxes. Again, the conductor is focused solely on the instrument, only at this point in the piece the direct connection between physical gesture and sound deteriorates.

Measures 140-144, the third example, are preceded by eleven measures (to be discussed below) in which the conductor for the first time clearly conducts the ensemble in no conventional manner whatsoever. In these bars, the conductor continues to utilize conventional conducting patterns; however, they no longer have any correlating effect on the performing musicians. By this point in the piece, it is also entirely possible that all the strings binding the conductor to the instrument have been completely broken. If that is the case, the conductor’s movements are entirely non-functional: there is no direct acoustic link to the instrument and there is also no perceivable reaction from the musicians. His/her movements are futile and conceivably a dystopia settles in: The soloist flails without an instrument and simultaneously wildly conducts a non-adhering ensemble.

Structure: from Chains to Dictatorship

When the methodology above is applied to Ghost of Dystopia, the analysis results in a dramatic story told in three parts. The conductor begins the piece on equal footing with all the members of the ensemble. Throughout the first section of the piece, he/she attempts to rise above the other musicians only to fail and rejoin the group for section two. By the time we get to the cadenza the conductor has succeeded in breaking free and celebrates as a soloist. Section three sees the conductor commanding the other musicians first in a conventional, brutal 2-beat manner. He/she then progresses to the point where only minimum gesture is required for maximum effect from the ensemble. At the end of the piece, Khubeev has the conductor take up a Christ-like pose, generating an intentional ambiguity with a chain-muted gong strike from the percussionist, asking: Is the conductor dead? If so, who killed him/her? Society? Or has the dictator become a god?12

Section 1

Section 1 begins with the first movement of the conductor in the very first measure of the piece and continues up to and including measure 56. The conductor’s movements are all primarily dedicated to the movement of the acoustic sensors (plastic boxes) across the glass plates. At rare moments in this first passage, such as in measure 43 (described above) the conductor seems to step briefly out of the role of soloist and functions as a quasi-conductor. That said, all the movements are strictly utilitarian and do not venture close to anything that could be recognized as conventional conducting gestures. Characteristic of this section is the link between sound (the acoustic sensors) and physical gesture (the movements of the conductor), which is abundantly clear to a visually attentive audience.

Section 2

Section 2 begins in measure 57 and continues all the way until the end of the conductor’s cadenza in measure 129. Distinctive to this section is the use of non-functional conventional conducting movements. These can be found and are introduced in measure 58. To this effect, Khubeev alters the notational style of the conductor’s part in measure 57, switching from the (in total) sixteen-line stave to a six-line stave. In the first section, Khubeev used traditional note-head notation in the conductor’s score. From section 2 onwards, the conventional conducting gestures are notated using graphic notation, vertical lines in the stave used to indicate movements in the hands. Although it seems conceivable that the conductor-soloist’s movements found in measure 58 and then later in measure 89 can be recognized as those a conventional conductor would employ, no discernable link can be found between the sounds produced by the musicians and the conductor’s movements. The conductor’s physical gestures are therefore non-functional in any traditional sense.

Section 2 culminates in a measured and improvised conductor’s solo: a cadenza.13 The notation during the solo is graphic and extremely difficult to replicate from one performance to the next. According to the composer,14 the conductor should attempt to break free from as many of the acoustic sensors as possible in the measures leading up to the cadenza, and especially during it. During any given performance, the fasteners that hold the strings to the soloist’s appendages break in a random order. For example, sensor 1 may break off first, followed by the 7th, 16th, etc. In the next performance the breaks may first occur on the opposing side of the instrument. Both this lack of predictability and the graphical notation can lead us to the conclusion that a certain amount of improvisation is required to perform this solo.

Section 3

After breaking free of the instrument (or as much of it as possible) the conductor is now free to openly conduct the ensemble. The final section of Ghost of Dystopia begins in exactly that fashion, and in a rather exaggerated manner. During the first ten bars of Section 3, measures 130-139, the conductor gesticulates an overtly, even brutally, clear two-beat pattern with both hands. The two beats are equal eighth notes and can be understood by a visually attentive audience to coincide with the rhythms being produced by the musicians. In addition to the two-beat pattern, the conductor is instructed to employ a traditional physical gesture for crescendo: an open hand moving from low to high. These gestures coincide with glissandos from low to high and crescendos that are performed by the musicians. Furthermore, the glissando/crescendo combinations are performed in stereo. The instruments seated on the conductor’s left-hand side are grouped together and so are the musicians on the conductor’s right-hand side. The conductor’s glissando/crescendo gestures are also made in a stereo fashion: left arm for the left side and right arm for the right side (See Figure 3).

In measures 145-149, the conductor shifts from functional conventional conducting patterns to functional non-conventional conducting gestures. The conductor and musicians have exactly the same rhythms in these measures. However, the conductor’s physical gestures could not be said to be recognizable as conventional conducting movement repertoire. Instead, Khubeev has instructed the conductor to: (see also Figure 4)

From bar 146 till the fourth beat of bar 149 “conductor” starts to make wide movements with straight hands in different directions on each beat. Then (from fourth beat of bar 147) he/she adds separate arm movements on each second eighth note, then (bar 149) adds separate wrist movements on each second sixteenth note for three beats.15

Measurable trends

Instrumental Soloist to Ensemble Conductor

Over the course of Ghost of Dystopia, we see the conductor-like figure make a transition from instrumental soloist to ensemble conductor. This does not happen linearly. There are even moments in the final section when the conductor regresses to an instrumentalist’s role (though dysfunctional: the instrument at this point is no longer in any playable state). In Section 2, the soloist first has choreographed conductor-like movements, however the composer has also written passages in which the audience could perceive the conductor as purely an instrumental soloist. However, in the large arc of the piece the conductor-soloist begins as an instrumental soloist in Section 1, then becomes a soloist utilizing conductor-like gestures in Section 2, and finally in Section 3, takes on the mantle of an ensemble conductor.

Bound to Free

When the transition described above is viewed from a different perspective, it becomes apparent that the conductor-soloist evolves from being completely bound to enjoying and even rejoicing in their freedom. Before a member of the audience has even entered the performance space, the conductor will already have been bound to the instrument. To ensure that no sound escapes the instrument, the conductor must remain completely still while the audience takes their seats. Only once all have subsided to silence may the conductor finally move. The initial physical gestures are all minute, miniature, and pianissimo movements. Throughout the first section, the conductor and ensemble as a whole gradually get louder and are afforded more freedom of movement.

With the commencement of the conductor-like movements in Section 2 and especially during the cadenza-solo, the conductor-soloist begins to break free of the acoustic sensors that bind him/her. Each movement loses its exactly timed (gesturally linked) unique sound. Non-functional conductor-like movement is for a short time (dystopically) associated with an instrument that is also, with each snap of the string, losing its functionality.

After finally applying functional and brutally clear conducting techniques and breaking free of the last few cords binding him/her to the instrument, the conductor begins to slowly raise their arms up towards the ceiling. Is it a gesture of praise? Is it religious or sacred in nature? Might it represent death or deification? Khubeev’s instructions are as follows:

From third beat of bar 152 “conductor” very gradually raises his/her hands till they will be parallel to the floor (on the level of shoulder, hands directed to the right and to the left, palms up). In this “cross”-position “conductor” should stay until the first sound from audience (after the end of the piece).16

Why a Conductor?

I will conclude this paper by discerning what detectable artistic and socio-economic motivations are present for specifically utilizing a conductor as a soloist in Ghost of Dystopia. After all, this work is performed with the assistance of a click-track and video score, so there is no need to utilize a conductor to temporally synchronize the ensemble. Also, every move the conductor-soloist makes has been strictly choreographed, so there is no room for any sort of spontaneous, impromptu artistry17 or practical faciliatory gestures that one might typically expect from the conductor. Below, I present three broad categories of motivations. First, I examine economic considerations for deploying a conductor as soloist in this piece. Second, I consider Khubeev’s reliance on conductor’s movement repertoire. And lastly, I will argue that the composer required a conductor to serve as the subject of his Ghost of Dystopia.

Economic

When looked at in a broad sense, ‘the economy [can be] defined as a social domain that emphasizes the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the production, use, and management of resources’.18 A tradition of the conducted (new) music ensembles exists. The ‘practices, discourses, and material expressions’ of a new music ensemble would include the relationship between the musicians and a conductor – two of its resources. This relationship is defined by certain keywords and key-gestures. For example, as Paul Verhaeghe explains in his book Identity, within a group of musicians, when one suggests that the music should be more agitato or when a conductor prepares and then gives a downbeat gesture, all present would comprehend.19

Without this tradition and the group’s keywords and gestures, Ghost of Dystopia would be meaningless. It relies on the audience’s understanding that there is a traditional relationship between the cue-giver (the conductor) and the cue-followers (the musicians). In this sense, the presence of an economic utilization of a conductor by the composer is present and detectable in Ghost of Dystopia.

Movement repertoire

Building further on Verhaeghe and based on an in-depth interview with composer Simon Steen-Andersen, within the framework of the Western art music tradition, specific conductor’s gestures can be seen to be generally recognizable. Their meanings, though the details may be open to interpretation, are also generally understandable.20 For example a conductor’s downbeat is recognizable as a starting point. The gesture is a downward motion made with one or both hands, with an ictus, or perceivable bounce, at the lowest point of the movement. Specifically, the ictus itself is recognizable as the exact moment of commencement: the point at which a beat begins. We can expect that, within the context of a performance, both the audience and the musicians would recognize this gesture as a beginning.21

This gesture, the downbeat, can be found at many points in Ghost of Dystopia. It has been shown above to be both functional and non-functional. For this reason alone, the non-functionality of the gesture, we can conclude that Khubeev has utilized a conductor in this piece for artistic visual reasons. More specifically, Khubeev employs the recognizable conductor’s movement repertoire to generate sounds on the plastic and glass acoustic sensors.

In Section 3 of Ghost of Dystopia, the work enters the functional realm of movement repertoire. The movements of the conductor are now quite clearly traditional gestures, and they function in a conventional manner. The musicians align their rhythmical passages with the gesticulated tempos displayed by the conductor. As shown above, they also align the timing of their glissandos and crescendos with gestures found in the conductor’s movement repertoire. The crescendo, for instance, is shown by the conductor in a fluid motion, raising his/her arm with the palm open and the arm extended.

The gestures in this third and final section, however, are strictly choreographed. Unlike conventional conductors, who to a large part improvise their expressive gestures (such as crescendos), Khubeev has clearly indicated these gestures and their scope in his score. The downbeat gestures themselves can be recognized as part of the pattern for a 2/4 measure, but those particular measures (see above) are written in a 4/4 time signature. The conductor is therefore not even fulfilling the conventional role of matching his/her pattern to the printed time signature.22 However, the gestures themselves will be recognized as functional. This is a clear artistic use, by the composer, of the conductor’s movement repertoire. A conductor is utilized in Ghost of Dystopia to bring to bear the generally recognizable conductor’s gestures, practicing a gesture that would normally cause the audience to expect one sort of event, but dystopically and through non-functionality receive another.

Furthermore, there is evidence that Khubeev relies on ‘performance ritual’23 to ensure that his soloist will be perceived as a conductor. He/she is placed in a conventional position: the musicians are seated in an arc (an open U-form with the opening of the U facing the audience) and the solo-conductor stands, facing the musicians in the opening of the arc. An audience brought up in the Western art music concert tradition can be expected by the composer to regard the soloist as a conductor.

Conductor as subject