29 – February 2021

clustered | unclusteredTaking Exception to Autonomy: On Arne De Boever’s Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism

Pieter Vermeulen

At least since the advent of postmodernism, aesthetic reflection is marked by a certain discursive bipolar disorder. For some, art remains a refuge from normality – an exceptional realm where the banality and compromise of everyday life finds itself temporarily suspended. At the same time, it seems to be received wisdom that artworks have been reduced to the status of mere commodities. In Autonomy, his recent book on the social ontology of art under capitalism, Nicholas Brown situates aesthetic thought in the tension between these two poles – between an unavoidable cynicism about the significance of art and the undeniable persistence of art in a world where, according to the cynical position, it should not be possible. Brown begins his book with a quotation from György Lukács: “Works of art exist – how are they possible?”1 How can art escape its wholesale reduction to the status of a commodity? For Brown, holding on to the promise of a not wholly commodified world requires that artists continue to assert the autonomy of art – in willful defiance of the heteronomous forces that afflict it.

Arne De Boever’s short 2019 book Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism, which provides the occasion for this cluster of essays, enters this bipolar space from the other side. For De Boever, the danger is not art’s irrevocable neutralization so much as its continuing singularity. His book opens with an account of the Toporovski affair, a well-publicized controversy over the questionable authenticity of a collection of Russian avant-garde art displayed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, Belgium. For De Boever, the fervor over the supposed inauthenticity of the collection points to the persistence of a kind of aesthetic exceptionalism, which he defines as “the belief … that art and artists are exceptional”2 – a belief that is thus threatened when, as in the controversy over the Toporovski collection, original and copy prove to be eerily interchangeable, fooling even specialists. De Boever’s lexical choice for “exceptionalism” rather than “autonomy” is deliberate: it allows him to explore the resonances between this aesthetic regime and a longer tradition of political and philosophical reflections on democracy and sovereignty – a tradition that culminates with Carl Schmitt’s famous dictum that “sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” The Toporovski affair shows that artists and their works remain endowed with a similar kind of sovereignty. This similarity is problematic: not least because of Schmitt’s enthusiastic embrace of Nazism, the relation between exceptionalism and democracy is at the very least complicated.3 Still, the continuity between art and politics also offers the book the opportunity to demonstrate the worldly relevance of art: because its position in the economic and political realms is so overdetermined, De Boever sees art as “a particularly good place to question exceptionalism” and to contribute to “a transgressive critique” of the political and economic regimes contemporary art inhabits.4

Cumulatively, De Boever’s discussion of a broad range of political thinkers (Schmitt, Agamben, but also Bonnie Honig and François Jullien) and a number of contemporary artists (Sam Durant, Alex Robbins, and Becky Kolsrud) begins to articulate an alternative sovereignty (or what the book also calls a democratic exceptionalism) within the realm of art – which is to say, without fully surrendering art to normality. This “unexceptional” art “unexceptionalizes” the “bad” exceptionalism of Schmitt and of dominant forces in the art world and makes art something worldly, something secular: “just art.”5

“Unexceptional art,” then, names an approach to art that shortcuts the disabling bipolar opposition between grandiose affirmation and facile cynicism. Neither ordinary nor extraordinary, unexceptional art maintains an irreducible relation with the political, the social, and the economic. One reason to prefer “sovereignty” and “(un)exceptionalism” over “autonomy” is that the latter term risks isolating art from all its worldly contexts – to suture its politics from all links to political action or organization.6 Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism’s promiscuous intertextuality and its virtuoso interdiscursive trajectories across the domains of art, aesthetic theory, political theory, metaphysics, and journalism exemplifies an awareness that the significance of art needs to be articulated in its relation to contiguous social realms. Art exists – but it risks ending up splendidly isolated from worldly relevance if it is happy to be merely autonomous. The notion of “sovereignty” is less conducive to such fantasies of withdrawal.

This refusal of autonomy has been an abiding concern in De Boever’s works since his first book. States of Exception in the Contemporary Novel, an exploration of the forms and politics of fiction after 9/11, takes issue with Carl Schmitt’s contention that the “form of aesthetic production … knows no decision.”7 De Boever objects to this exaltation of the literary and the artistic as a “realm of nondecision”8 and instead shows how decisions in the aesthetic realm complicate and deconstruct the political, social, and economic ramifications of ethical and political decision-making. De Boever’s intuition that an affirmation of autonomy would amount to a spectacular act of self-marginalization also informs two later books about contemporary literature, which more affirmatively explore literature’s capacity to engage and unwork the societal structures and systems that (fail to) sustain us: in the case of Narrative Care, he affirms the power of literature to warp the operations of the welfare state, the camp, and other biopolitical institutions; in Finance Fictions, the novel is credited with the power to put on display and devise an appropriate ontology for the often intractable and fatally abstract powers of the financialized economy.9

There is no literature in Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism (except for a short discussion of Ben Lerner’s 10:04). The book instead picks up the philosophical tenor of De Boever’s earlier explorations of the elasticity of the notion of sovereignty in his 2016 book Plastic Sovereignties. That earlier book mobilizes the work of (especially) Giorgio Agamben and Catherine Malabou to counter customary conceptualizations of sovereignty with a more democratic alternative form of sovereignty: what the book calls “a a poor, plastic sovereignty that would remain sovereign – but beyond the structure (ontological, linguistic, political) that … inform[s] the concept of sovereignty”; in this way, “Agamben’s and Malabou’s thoughts yield a theory of plastic sovereignty that, from the field of aesthetics (plasticity) deconstructs the political structure of sovereignty (its two-body problem).”10 Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism continues this project of drawing on aesthetic resources to destabilize customary accounts of sovereignty. The plural in the title of Plastic Sovereignties is crucial: De Boever’s approach invariably relies on the articulation of different artistic and theoretical trajectories that intersect in ways that cumulatively deflate all too exceptionalist accounts of art and politics alike. It is an approach that entangles the concepts it mobilizes rather than affirms any kind of purity or autonomy. De Boever’s work offers an ongoing intellectual and critical project rather than a consolidated position—and it is a project that has more recently moved beyond the confines of Western thought to explore the affordances of Chinese art and philosophy (most notably, in a recent book on the work of the French Hellenist and sinologist François Jullien).11

It is in this open-ended and dialogic spirit that the four contributions to this cluster engage with Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism. In her essay, Rika Dunlap picks up on an opening that the book makes in a long footnote on the distinction between the Kantian sublime and the beautiful. Fleshing out De Boever’s suggestion that the latter might contribute to a more wholesome exceptionalism than that of someone like Schmitt, Dunlap shows how Kant’s account of genius (as a capacity that no person ever fully tames rather than as a domesticated possession) produces the kind of unexceptionalism that De Boever finds in Chinese art and thought; for Dunlap, a conceptual trip to China might be a good idea, but it is not necessary, as the salutary exceptionalism De Boever chases resides at the very heart of Western reflections on the aesthetic. Winnie Wong, in her contribution, also complicates the opposition between Western and Chinese art and thought. Wong renders three “tales” that report on her fieldwork in Dafen village, in China, the world’s largest production center for hand-painted oil paintings. Wong illustrates the persistence of aesthetic exceptionalism in the most mundane of artistic sites. At the same time, the sober style in which the tale documents that persistence may paradoxically make them available for the kind of unworking, decreation, and “unexceptionalization” that De Boever pursues in his book.

The two other essays in this cluster push art’s capacity for self-unexceptionalization in directions invited but not pursued by De Boever’s book. Tim Christiaens’ essay worries that De Boever’s artistic examples do not go far enough in unworking the powers of exceptionalism. What looks like salutary contestation and democratic deliberation may, in a fully commodified art world, end up being recuperated by the artistic hype machine, and accrue even more symbolic capital to artists – like Sam Durant, in an example De Boever discusses at length – who find themselves chastised or cancelled. Going fully unexceptional, Christiaens argues, may involve unembarrassedly embracing the banality of a platform like YouTube and capitalizing on its power to neutralize the power of sovereign authorship. In his essay on the aesthetics of what he calls “infinite correction,” Stéphane Symons explodes the distinction between aesthetic exceptionalism and a more worldly unexceptionalism by introducing a third mode of making art matter: in a terminal age of climate change, Symons suggests, art and literature might take up the task of demonstrating the depletion of imaginative, material, and political resources and refusing to mine reality for unanticipated potentialities – if only because pointing to the unacceptability of the status quo might be a more urgent task.

Works of art exist – how are they possible, if all they tell us is that life is no longer possible? It is a tribute to Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism’s catalyzing potential that four thinkers were willing to take up the work’s invitation to reflect on the place of contemporary art without recourse to either deflation or exaltation, and to revisit the archive of aesthetic and political thought to come up with powerful engagements with such thinkers as Kant (in Dunlap), Agamben (in Christiaens), and Furio Jesi (in Symons) to continue the effort to preserve art and save it from indifference and autonomy alike.

Notes

- 1Nicholas Brown, Autonomy: The Social Ontology of Art under Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 1.

- 2Arne De Boever, Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism (Minnesota: University of Minneapolis Press, 2019), 5.

- 3De Boever, Against, 6.

- 4De Boever, Against, 7.

- 5De Boever, Against, 80-81.

- 6For a critique of Nicholas Brown’s work in these terms, see Myka Tucker-Abramson, “The Minimal Politics of Autonomy,” CLCWeb vol. 22, no. 3 (2020).

- 7Arne De Boever, States of Exception in the Contemporary Novel: Martel, Eugenides, Coetzee, Sebald (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 7.

- 8De Boever, States, 9.

- 9Arne De Boever, Narrative Care: Biopolitics and the Novel (London: Bloomsbury, 2014); Arne De Boever, Finance Fictions: Realism and Psychosis in a Time of Economic Crisis (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018).

- 10Arne De Boever, Plastic Sovereignties: Agamben and the Politics of Aesthetics (Edinburgh ; University of Edinburgg Press, 2016), 35-36.

- 11Arne De Boever, François Jullien’s Unexceptional Thought: A Critical Introduction (Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

a

clustered | unclusteredIs Chinese Philosophy the Only Antidote to Aesthetic Exceptionalism?

Rika Dunlap

Does an artwork lose its aesthetic value when its authenticity is called into question? If so, why is that the case? Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism takes us on a thrilling journey that reveals the murky side of the art world with scandals in exhibitions and artworks that provoke much thought for anyone who thinks that fake art has no place in an art museum. Beginning with the story of the Toporovski Affair, in which the authenticity of art works attributed to Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich was called into question, De Boever invites us to rethink the undemocratic way in which we value artworks. According to De Boever, the Toporovski Affair was enabled by what he calls aesthetic exceptionalism: the widely accepted belief that art and artists are exceptional, that art is immune to the ordinary rules that govern ordinary experience.

Instead of eliminating exceptionalism that surrounds art altogether, De Boever argues for a democratic kind of exceptionalism, one that is rooted in aesthetic judgment that unworks the undemocratic assumptions about art and artists, as he engages in a cross-cultural analysis of aesthetic theories in Western and non-Western traditions. In particular, François Jullien’s work on Chinese philosophy plays an important role in establishing his main argument for aesthetic unexceptionalism as an alternative democratic theory of art, which can, De Boever believes, resolve the political and economic tensions within the art world today. To do this, he delves deeper into the theoretical foundation of aesthetics itself, thereby arguing that these political and economic issues emerge from the metaphysical assumptions that characterize much of aesthetics in Western philosophy. Therefore, the book endeavors to resolve two issues: the undemocratic kind of aesthetic exceptionalism that demarcates valuable art from non-valuable art (or genuine art from fake art) and the metaphysical foundation of Western aesthetics that allegedly fuels this exceptionalism. To see this, we need to clarify what De Boever means by his central yet ambiguous claim that “art and artists are exceptional.”

In one sense, art and artists are exceptional because they can override our ordinary experience, for when it comes to art, we have a tendency to suspend our judgment and think, “Well, it is art!” To explain this privilege that we grant to art and artists, De Boever introduces the concept of sovereignty from the political theory of Carl Schmitt, in which the sovereign is famously defined as the one who declares the state of exception to suspend the ordinary governance of the law to maintain order. Comparing art and artists with political sovereignty, De Boever points out their similarities, inasmuch as art calls for the suspension of our ordinary judgment by asserting its autonomy. This comparison between art and political sovereignty remains rather abstract and ambiguous in Chapter 1, but the clearest illustration of it comes in Chapter 2, in which Sam Durant’s Scaffold is discussed as a prime example of aesthetic exceptionalism. Scaffold is a controversial work that showed a 1:1 scale of the gallows that had killed thirty-eight Dakota men. Despite Durant’s intention to criticize the abusive power of U.S. sovereignty, De Boever argues that it ended up showing the audacious sovereign-like attitude of the artist himself: Durant was guilty of invoking the undemocratic kind of aesthetic exceptionalism that exonerated his work from ordinary judgment, and believing that somehow he, as an artist, could stand outside of history and create a replica of the death device as long as his creation was situated in an art museum. What this example shows is that art and artists assume their exceptionality because we somehow think that art exists in a transcendent space where it can escape the scrutiny of the ordinary rules.

How did this exceptionalism emerge in the first place though? The answer to this question is the second aim of this book, namely the criticism of Western aesthetics, as De Boever attributes aesthetic exceptionalism to the rise of aesthetics in the history of Western philosophy. This transition of focus from exceptionalism in the art world to the philosophical foundation of aesthetics seems like a leap, and this is why we need to clarify the book’s ambiguous claim that “art and artists are exceptional.” To recall, aesthetics deals with the judgment of taste and the notion of genius as the special artistic capacity granted only to a select few with the god-like power of creating their own rule of presentation. One unavoidable example is the aesthetic theory of Immanuel Kant, whose work on the notion of the genius and the aesthetic judgments of the beautiful and the sublime remains influential even today. Kantian aesthetics is not the main topic of De Boever’s book, but given that Kantian philosophy historically helped solidify the foundation of aesthetics after Baumgarten, I think it is illuminating to discuss Kantian aesthetics in the context of aesthetic exceptionalism.

In Kantian philosophy, aesthetic judgment is distinct from determinative judgment: it is a type of reflective judgment in which the concepts of understanding do not control the imagination to subsume the manifold of intuition. In that sense, aesthetic judgment deals with appearances that resist our ordinary judgment. Kant defines genius as the artistic capacity to create such appearances that suspend the usual dominance of understanding over sensibility. It is against this philosophical background that De Boever argues that artists with genius assume that they are endowed with a ‘sovereign-like’ power that defies the rules of our ordinary experience. To fully understand the link between the ‘sovereign-like’ power of an artist and aesthetic exceptionalism, we need to examine two distinctions that De Boever does not elaborate in detail: the distinction between the beautiful and the sublime in aesthetics, and the subtle but crucial distinction between genius as an artistic capacity and genius as an artistically exceptional person. While I am more or less sympathetic to De Boever’s claims about the metaphysical assumptions of Western aesthetics and why Chinese philosophy can be a remedy to this, I also think there are some possible responses within Western aesthetics that can combat the undemocratic kind of exceptionalism (although De Boever seems to reject this possibility indirectly through his discussion of Agamben’s aesthetics, which he sees as fatally trapped by the limitations of Western thought.) I will explain these points in the remainder of this essay.

First, I think it is beneficial to separate the two kinds of aesthetic judgments in Kantian philosophy to clarify De Boever’s ambiguous claim that art and artists are exceptional. To be fair, he does refer to the differences between the beautiful and the sublime in the book, though only in the footnotes.1 Therefore, it is important to highlight the differences here to see the distinct ways in which aesthetics can be undemocratic.2 I think it is easier to see why the aesthetic judgment of the sublime in Kantian aesthetics resembles the exceptionalism of political sovereignty, given that the sublime showcases the supreme power of reason to grasp the unrepresentable. If we are to understand that artists are capable of creating a sublime presentation, then the imagination of the spectator ceases to be free in front of this grandiose appearance that the artists creates. Reason’s abrupt interruption in the judgment of the sublime, I think, is much more similar to the power of the political sovereign that issues a higher-order rule to suspend the law to maintain order. In other words, the spectator is not free in the aesthetic contemplation of the sublime, inasmuch as reason dictates the way in which the spectator is supposed to see the unrepresentable.

When it comes to the aesthetic judgment of the beautiful, however, it is harder to see the similarities between aesthetic and political sovereignty. In fact, it seems to do the opposite of what the sublime does, given that in the case of the beautiful, the imagination engages in a free play with the understanding. The suspension of the ordinary rule in the judgment of the beautiful is characterized by what Kant famously calls purposiveness without purpose, in which the imagination breaks its ordinary subordination to the faculty of understanding. Since there is no concept under which the manifold of intuition can be subsumed, Kant asserts that the genius, in creating a beautiful presentation of fine art, does not understand its own rule of presentation. Kant explains: “Genius itself cannot describe or indicate scientifically how it brings about its products, and it is rather as nature that it gives the rule. That is why, if an author owes a product to his genius, he himself does not know how he came by the ideas for it.”3 To put it differently, the person with genius, even if he or she is the creator of the beautiful appearance, has no special understanding when it comes to the rules of the artwork. Thusly understood, this suspension of understanding in the aesthetic judgment of the beautiful creates a space for free aesthetic contemplation, a democratic space of equality between the artist and the spectators. This democratic potentiality of genius and aesthetic contemplation is something that De Boever does not discuss in detail, even if it could assist his project of breaking with aesthetic exceptionalism.

Second, the distinction between genius as artistic capacity and genius as an artistically exceptional person needs to be highlighted to appreciate that the artist does not enjoy the privilege of a special understanding as the creator of the work. This separation between the artistic capacity and the person who possesses it secures a democratic space of equality between the artist and spectators. In fact, I find this democratic possibility in Rancière’s aesthetics, although De Boever does not seem to agree. In Chapter 1, De Boever identifies the traces of Schmittian sovereignty in the aesthetic theories of Badiou and Rancière, but I think Rancière’s aesthetics is more democratic than De Boever presents. Rancière highlights the equality between the artist and the spectators in the aesthetic regime of art, a politically significant narrative of art that delineates art as that which is capable of suspending the hierarchy between the ruler and the ruled. This new regime of art that Rancière finds in aesthetics focuses on art as that which gives rise to the aesthetic experience of equality, where no entitlement to rule endorses the foundation of democracy. De Boever redeems Rancière’s political theory in Chapter 4 by agreeing with Rancière that anarchism is the foundation of democracy, but I think it would have been helpful to draw out some of the democratic aspects of his aesthetics. According to Rancière, aesthetic contemplation enables what he calls the redistribution of the sensible by creating an anarchic space of equality that disrupts the ordinary hierarchies between the ruler and the ruled, the expert and the novice, and the artist and the spectators.

If aesthetics creates a democratic space of equality that Rancière celebrates as the new regime of art, then why does De Boever claim that exceptionalism pervades this space? De Boever’s answer to this specific question is offered only indirectly, but it is actually a crucial move in his effort to challenge Western aesthetics. That is to say, genius as the artistic capacity gives a god-like status to the artist who possesses it, for the artist is now seen as a conduit to the divine realm of the supersensible, even if he or she does not understand the aesthetic rules of its creation. In other words, De Boever asserts that Western aesthetics cannot be democratic, precisely because the idea of genius requires the dualistic worldview that Kant endorses in his transcendental philosophy—the dualities of appearance and reality, matter and form, and zoe and bios that can be traced back to the Greeks. It is this assumption of dualism that De Boever aims to contest with François Jullien’s work on Chinese philosophy, in which everything is fundamentally one. Hence, the crucial question that De Boever poses here is this: can we establish aesthetics and its democratic implications without the metaphysical assumption of the supersensible? Needless to say, Kant cannot do this without his transcendental assumptions. How about Rancière? This is debatable, although I think he can.4 De Boever’s own answer seems to be that metaphysics is an essential part of Western aesthetics, for it is this dualistic foundation that gives artists an exceptional status that resembles political sovereignty. To this, De Boever proposes a more radical solution, which he finds in Jullien’s work on Chinese philosophy.

In Chapter 5, De Boever compares and contrasts the subtle ways in which Jullien and Agamben differ in their explanations of the nude. In this way, he demonstrates why Chinese philosophy is superior to Agamben’s aesthetics in order to question the democratic possibilities of Western aesthetics. Agamben defuses theology and metaphysics by reducing reality to appearance, but De Boever thinks that Agamben perpetuates the problem of duality by beginning with the split between zoe and bios. Furthermore, De Boever thinks that Agamben’s appeal to the beautiful face in his discussion of the nude actually invokes dualism and metaphysics along with it, inasmuch as beauty points toward the supersensible, thereby reminding us of the undying yearning for the eidos in the transcendent realm. Jullien, on the other hand, declares that “[e]verything is there,” inasmuch as Chinese philosophy does not assume the duality of appearance and reality. A good example to illustrate this point is the notion of xing in Chinese philosophy. Although xing can be mistakenly understood as an essence or a form, Jullien points out that it should be translated as ‘formation’ instead to eliminate the Greek ontological connotations. For this reason, De Boever thinks that there is a fundamental difference between the positions taken by Agamben and Jullien when it comes to aesthetics: while Agamben praises beauty and perpetuates the problem of aesthetics that he aims to contest, Jullien, through his work on Chinese philosophy, shows that the aesthetic ideal should be earthly, mundane, and even bland. Ultimately, it is only in this aesthetic ideal of blandness that De Boever finds the democratic kind of aesthetic (un-)exceptionalism, one that displays the fullness of this world without appealing to transcendence.

De Boever’s project is ambitious. Perhaps it is too ambitious to accomplish what it promises to do in a single book. Because of this, I am left with two final thoughts. First, since his aim in this book is to challenge exceptionalism in the art world and the Western aesthetics that enables it, I wish he had spent more time discussing the canonical theories of aesthetics to explore the historical context of Rancière’s aesthetics. Even if De Boever disagrees with what I say about the democratic potentiality of Rancière’s aesthetics, the way De Boever shows the resemblance between political sovereignty and art/artists in chapter 1 invites questions, since he does not provide the philosophical context of these claims by Rancière or Badiou. As for Rancière, contemporary art in the aesthetic regime creates a democratic space of anarchism by suspending the ordinary judgment about who has a say in what. If De Boever can effectively show that the theoretical foundation for the aesthetic regime of art actually requires metaphysics and the dualistic assumptions of Western philosophy, then I think it offers a much more fundamental criticism of Rancière’s political claims about art.

Second, I wish De Boever had elaborated the role of Jullien’s work on Chinese philosophy in depth to explain why it is a remedy for the exceptionalism of Western aesthetics. De Boever brings up Chinese philosophy in chapters 3 and 5, but the significance of Jullien’s work is somewhat deemphasized throughout the book. With that said, Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism prepares the reader for De Boever’s latest book, François Jullien’s Unexceptional Thought, in which he continues his work on aesthetic unexceptionalism by detailing Jullien’s comparative philosophy. While I offered some questions and criticisms in this essay, De Boever’s work is an ambitious and exciting project of comparative philosophy that critically engages with the political and economic problems of the art world today.

Notes

- 1De Boever makes references to these differences twice: in footnote 21 on page 18 and in footnote 10 on page 70. Arne De Boever, Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 18 footnote 21 and 70 footnote 10.

- 2Here I would like to emphasize that aesthetics can be undemocratic, but is not necessarily so. As I explain, some Western aesthetic theories are democratic, although De Boever may disagree on this.

- 3Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. Werner S. Pluhar (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987), §46, 308.

- 4I do think that Rancière’s aesthetics focuses more on the political implications of art, thus it is much less metaphysical compared to Kant’s aesthetics.

b

clustered | unclusteredThe Age of Digital Bricolage

Tim Christiaens

If I had to choose an auspicious sign for the approach of the new millennium, I would choose this: the sudden nimble leap of the poet/philosopher who lifts himself against the weight of the world, proving that its heaviness contains the secret of lightness, while what many believe to be the life force of the times – loud and aggressive, roaring and rumbling – belongs to the realm of death, like a graveyard of rusted automobiles.

— Italo Calvino1

Rothko in the Repair Shop

Imagine you are sitting at the Tate Modern Museum, mesmerized by one of Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals. You are entranced by the vivid struggle of the reds and blacks devouring the canvas. The black void is sucking you into an earthy pit of existential dread. But then, a mysterious person comes up to you, surely some demon pulling you back into the world of the living. This demon, however, comes with no happy consolation. He is a professor from the local Visual Studies Department and he informs you that the painting is actually a forgery. The real Rothko paintings are currently in repair. Some mentally disturbed individual apparently tried to attack the painting with a knife – probably trying to get some of his sanity back by stabbing into the black vortex. You have not been watching Rothko’s actual murals at all, just some copies … Would you not feel betrayed now? Would this revelation not devalue your original experience? Fake, just like the painting.

If this would be your reaction, you suffer from what Arne De Boever calls ‘aesthetic exceptionalism.’ According to De Boever, the contemporary art scene exaggerates the importance of originality and authenticity. Its business model consists of depicting artistic objects as somehow exceptional or sacred. They are not meant for actual use, but increasingly as investment opportunities for venture capitalists, who buy up warehouses full of artworks hoping that one of these creations will become the new Rothko and sell for millions of dollars. Ironically, the more detached art becomes from the realm of everyday use, the more valuable it becomes as a speculative commodity. This business model requires the work of art to be recognized as exceptional: it is endowed with quasi-magical qualities to revolutionize its audience’s worldview; the work of art is the artist’s genius taking solid form. It ruptures our everyday experience of the world by bringing the depths of the earth to the surface of human perception, as the order of the sensible is temporarily suspended. The world ought to never feel the same again after watching a Rothko. No wonder people are willing to pay hard cash for such a life-changing experience: you are not just buying a smart investment, you are gaining a new perspective on the universe.

Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism interrogates the implicit politics of such an ecstatic adulation of ‘exceptional art’ in the art scene – the assemblage of critics, curators, and successful artists that decide over artistic trends and fashions. The book not only bewails the inflated egos this trend generates among artists and critics, but it also sees through its undemocratic assumptions. Who gets to determine what counts as ‘art’? Who is sovereign enough to decide on the exceptional? Who gets the authority to suspend the order of the sensible, and for what purpose? Whether we are talking here about modernist, postmodern, or Renaissance art is beside the point, as these questions apply to the sociological composition of the artworld as such. Famous Renaissance artists frequently let their students paint unimportant sections of their paintings, such as trees in the background. Are these elements less exceptional or artistic? Apart from the price tag, there is nothing to really distinguish the real from the fake Rothko painting. There is nothing to fundamentally separate Duchamp’s Fountain from an everyday urinal, yet the museum curators would not be amused if someone were to take a leak in Duchamp’s masterpiece. This is odd, given that is was quite literally designed and produced for that purpose. Yet the artist’s signature pulls the urinal away from its ordinary use and puts it on a pedestal to be sanctified and admired.

De Boever lays bare the performative dimension of the artistic signature: objects become art thanks to the institutions that uphold the artworld and its standards as exceptional and sacred. An artist like Duchamp receives the authority to call a urinal art thanks to his institutional position within the artworld. If some stranger were to walk in the Tate Modern’s lavatory and admire the urinals, he would surely be dragged away together with the assailant of Rothko’s painting. Yet Duchamp can revolutionize ‘art’ with a similar gesture. In De Boever’s view, the artworld is foremost a plutocracy where a few insiders get to choose what counts as art and what does not: aesthetic exceptionalism, on his analysis, is the story insiders tell themselves to justify their powers in the art scene.

Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism has, however, not given up on the contemporary art scene. It wishes to democratize the institutions from within, a project the book actually shares with Duchamp’s original intention when he invented the notion of the ready-made. According to John Roberts and Maurizio Lazzarato, the ready-made was meant to detach artistic merit from privileged skills in order to democratize the artistic endeavor.2 De Boever’s book mobilizes Walter Benjamin’s plea for a politicization of aesthetics against the exceptionalists, who would like to reserve art’s special powers for themselves. If our sensible experience of the world is to be suspended, the argument of the book goes, then let it be by a democratic force. Much in the spirit of Duchamp’s ready-mades, De Boever subsequently looks to artists who disrupt the traditional dichotomies between copy and original, authentic and fake, painting and signature. Notably, he praises Sam Durant’s Scaffolds not for its brutal depiction of colonial violence – the hanging of 38 Dakota natives in 1862 – but for the artist’s openness to criticism from the Dakota people. When the latter took offense with such a monumental rendition of a traumatic event in their history, Durant agreed to have the installation taken down and buried. In such events of popular protest, the artist’s exceptional status is put into question. Through the cracks and fissures of official institutions, the people’s power seeps into the artworld.

Democracy and Signatory Power

Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism hesitates between two positions. On the one hand, De Boever resolutely argues ‘against aesthetic exceptionalism’ and calls for the destitution of art, but, on the other hand, he seems satisfied with examples that merely put a question mark behind the privileges of the artistic plutocracy without profoundly challenging these privileges. The Dakota people acquired the right to respond to Durant’s insensitive project, but they did not receive the right to participate in the artistic production process itself. The signatory power of the artist remains firmly rooted in the hierarchies of the contemporary art scene, while the public has merely received a forum to express its complaints. One could even cynically suspect that some artists intentionally provoke such public outcries to build up momentum for their exhibitions. Democracy, in such cases, turns out to be free promo for the exceptional artist.

Another of De Boever’s examples is Alex Robbins’ Complements exhibition. Robbins presents detailed copies of famous modernist paintings, but he presents them in the complementary colors and, mostly, on a different scale. Robbins recreates, as it were, the negatives of famous paintings, even including the original artist’s signature as part of the composition. This practice deconstructs the dichotomy between original and copy and it also reduces the artist’s signature to an element equal to the other parts of the painting, but does it really dissolve the signatory power of the artworld? There is no reason to assume any changes were made in the hierarchy of the artworld after the exhibition of these works. They were, at most, question marks putting the viewer at a critical distance from artistic presumptions: should we value originals so much? Is the signature the final appropriative act of a creative process or a mere part of the painting? These questions do not alter the hierarchical composition of the artworld: all quiet on the artistic front. The utter desacralization of art, a genuine intervention ‘against aesthetic exceptionalism,’ I submit, calls for more radical projects, such as participatory or community art.3 Merely questioning the hierarchies of the artworld does not suffice if there is no simultaneous call for a real alternative. If such an affirmative dimension remains absent, De Boever’s deconstruction risks becoming an empty gesture: one momentarily questions the hierarchical world of aesthetic exceptionalism, but one easily returns to business as usual. Exposing that the emperor is naked is not the same as abolishing the empire. A genuinely emancipatory theory of art should articulate and affirm alternatives to the empire of signatory power.

To explore possible escape routes from the institutional field of the art scene, I would like to first define the problem more clearly. If art is really the product of performative practices, if it is the artist’s signature and the latter’s approval by the artworld that define it, then there is an inegalitarian strain rooted in the institutional field itself. The artist signs, the critics ratify the signature, the public watches from a distance (and, however critical it is, ends up reinforcing the authoritarian institutions). The performative power of the signature and of the ratifying authorities remains firmly in place. According to Lazzarato, the performative is “always more or less strictly institutionalized such that its ‘conditions’ as well as its ‘effects’ are ‘known in advance.’ In this way, it is impossible to produce any kind of rupture in the assignment of roles and distribution of rights (to speak).”4 Performatives like the artist’s signature elevating an artefact to the status of art only succeed because there are clear pre-determined roles and conventions that govern artistic practice. Art only works insofar as these rules are observed.

This rigidifcation of art puts an authoritarian strain into the argument that can be traced with some help from Giorgio Agamben’s theory of sovereignty in The State of Exception.5 In contrast to his earlier writings, Agamben there argues that sovereign rule has two dimensions: potestas and auctoritas, power and authority. The Latin terms derive from Roman law, where individuals needed authorization from their pater familias in order to successfully perform legal actions. A legal complaint, for instance, would only be valid if the head of the household had ratified the complaint.

Agamben applies this distinction between power and its authorization to contemporary politics. On the one hand, there are ‘powers’ that implement a sovereign regime. They enact the will of the sovereign, either by law or by extraordinary measures in times of emergency. These institutions, however, need authorization from a higher might in order to become efficacious: their choices only embody the will of the sovereign if this sovereign grants its subordinates the authority to speak in its name. A policeman, for example, can legally shoot a protestor if and only if he is authorized to do so by his superiors. By wearing the police uniform and the insignia of the state, the policeman is authorized to speak – and kill – in the name of the state. Such symbols convey the auctoritas that ratifies the actions of the potestates.

One can understand artists’ performative signatory power in a similar light: they possess the capacity to sign an artefact and call it art, but this proclamation is only effective thanks to the artworld’s authorization of this power. Artists only succeed in calling a urinal, a scaffold, or the negatives of a painting art because the assemblage of critics, curators, academics, and others that constitute the artistic scene grant them that power. This group of people might not constitute a single sovereign institution like the state, but they still operate as if they did exert a final, uniform judgment. Whatever whispers come from the highest circles of the artworld eventually becomes canon for those below. The artist needs these whispers, the insignia of power, to be able to speak in the name of art. If the institution of art really is structured as a hierarchy of auctoritas and potestas, the social roles of all participants in the artworld are pre-determined. The public never has a more substantial role than passively contemplating and reacting. The artworld’s aesthetic exceptionalism promotes objects to the privileged status of art, then, on the basis of a collaboration between artists and their institutional auctoritates. The public is presented with a finished product, ready-made, stamped with the label of ‘fine art.’ Examples like the Dakota people’s show the audience can subsequently resist and refuse the products that are created in that way, but this does not mean that they can collaborate in the artistic process itself. They are allowed to engage with the artwork, even critically, but only on the artist’s terms authorized by the artistic establishment. Popular opposition is doomed to remain nothing but an afterthought.

If we accept this analysis of the power-dynamics in the artworld, the deconstructions presented in Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism do not suffice to fulfil the book’s laudable aspiration: the democratization of art. To allow his project against aesthetic exceptionalism to also move beyond aesthetic exceptionalism, De Boever needs more than artists that are critical of the artworld but ultimately work in that same world and respect its power relations. De Boever needs counter-institutions that displace and upset the established hierarchy of the artistic field. The deconstruction of aesthetic exceptionalism in De Boever’s book should be supplemented with a veritable alternative that dismantles the signatory power of the artworld. New institutions with new social roles for the various participants are in order to fulfil the democratic promise of De Boever’s book. As long as one stays within the artistic field and its power relations, there is no final dismantling of the exceptional signatory power of the artworld. If art should really be liberated from its sacred status and put up for common use, then someone must storm the heavens of Tate Modern and the Metropolitan Museum.6 Someone should ask the assemblage of artists, critics, and curators: Who are you to call this art?

The Unexceptional Art of Cover Songs

How can we imagine counter-institutions for a post-exceptionalist age? Starting from scratch is ill-advised. Utopias rarely grow if they are not firmly grounded in the soil of social reality. One thus has to look for seeds on the surface of already existing institutions. I would like to turn to one decidedly unexceptional counter-institution for the artworld: YouTube. The internet provides a platform for artists who have not received authorization from the upper regions of the artworld: undiscovered comedians, poor video essayists, musicians who did not get their multibillion-dollar record deal. Admittedly, there is no need to be naive about the democratic potential of the internet. It is largely owned by giant monopolistic corporations that make individuals incessantly fight for attention. The YouTube algorithm distributes the public’s gaze unevenly and new social media elites have already emerged. The big tech corporations risk becoming twenty-first century sovereigns, deciding what counts as art within the opaque parameters of their algorithms. Individual users, for their part, have to ceaselessly struggle for their place in the spotlight. However, for those of us who are not Hegelian beautiful souls – criticizing everything that does not attain absolute moral purity but always refusing to get their hands dirty – there is no escape from murky ambiguity. There is still something to be gained from exploring the internet’s potential to undermine the signatory power of the artworld.

YouTube grants a vibrant platform for the continuous creation and recreation of art. There is never a finished product; every video provides the opportunity for the public to make its own videos in reaction to established content. What looks like a finished product often proves to be the ignition for a whole new creative process.7 The chain reaction never stops, but proliferates across the platform. YouTube has, for instance, perfected the unexceptional art of cover songs. While the website mercilessly blocks copyrighted materials, cover songs are usually exempted from this practice. The cover song nonetheless undermines the traditional dichotomy of copy and original: one artist copies another artist’s work, but meanwhile makes it her own and reveals new dimensions to the song the previous artist might have missed. A skillful cover artist can turn an upbeat party song into a melancholic elegy. The cover song adds an originary supplement to the original: it adds something extra and inessential, but it also definitively alters the original in the process. Who can ever listen to Screamin’ Jay’s “I Put a Spell on You” again without hearing Nina Simone’s version between the pauses? Internet platforms like YouTube have amplified the art of cover music into unseen territory. You like Johnny Cash’s “The Ring of Fire,” but you are also a death metal enthusiast? No problem, someone will have made a crossover. Want to hear a folk version of Lorde? No worries, here you go. Or a dance-worthy version of Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid”? What are you waiting for! Any song you have never known folds in unto itself and becomes something new. The supposed original becomes nothing more than a blueprint for infinite variations.

In his book The Game, Alessandro Baricco aptly summarizes the spirit of this age of digital bricolage where the difference between artist and audience dissolves: “you bring everything in movement. You intersect. You connect. You overlap. You mix. You possess cells of reality made available to you in a simple and easily usable way. But you do not just use them, you work on them … You build and destroy, then you build some more, and afterwards, you destroy again endlessly. You need only speed, superficiality, and energy. Your presence among things is a movement, never immobile. Delving into depths only slows you down; the meaning of anything depends on your capacity to make it move at the appropriate speed.”8 In the ideal scenario, one loses all memory of an original. Just like folksongs from the distant past, famous contemporary songs become nothing but tools for the construction of new melodies and rhythms beyond the need for an ‘original artist.’ People can be excused for not knowing that it is not Johnny Cash but Trent Reznor who is the ‘original artist’ of “Hurt.” Who originally made folksongs like “Bella Ciao” or “O Holy Night” is entirely irrelevant – they are predominantly stock tunes for infinite variations. YouTube allows something similar for contemporary music: any amateur singer can creatively deploy and redeploy popular music in their own style. The public has become part of the creative process and the artwork itself is in everlasting flux across these multifold renditions. On the internet, there is no original form, only perpetual formation and transformation.

In a once famous phrase from his The Role of the Reader, Umberto Eco calls this form of art ‘open works.’9 The so-called ‘original artist’ in this case, only creates a part of the artwork and leaves it to her audience to complete it. Luciano Berio’s “Sequence for Solo Flute,” for instance, predetermines only the sequence and intensity of the musical notes, but not their duration. Musical composition becomes a collaborative effort between the composer and a potentially infinite multitude of performers. Every time Berio’s “Sequence for Solo Flute is played,” it becomes essentially a new and unique composition. There is no ‘primordial’ composition that acts as an anchor to the infinite iteration of its performances: There is only the ‘starters’ package,’ so to speak. Internet platforms can transform all music into open works. There would be nothing to grant one artist’s rendition of a song specific precedence over others’. From the perspective of open works, there are not original songs but only cover songs.

When the Bricoleur Visits Tate Modern

The idea of digital bricolage and the aesthetic of the open work provide more than a mere exercise in deconstruction: a promising alternative to aesthetic exceptionalism and the signatory power of the art scene. Contemporary art endows the artist with an exceptional status and sanctifies her art for the sake of economic gain and political power. Artistic institutions should allegedly decide which artworks disrupt everyday life. Only those artefacts sanctioned with the critics’ blessing can become lucrative commodities of speculative investment. Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism successfully exposes this problem, but it is less interested in providing an alternative avenue. De Boever undermines our faith in the pristine exceptionality of art, but he does not attack the institutions that profit from this exceptionality. The artists in his book take an ironic distance from the art scene, but they ultimately remain imprisoned in its assumptions. To move beyond aesthetic exceptionalism, we have to affirm counter-institutions that dismantle signatory power itself.

Internet platforms have some potential in this regard. They are marked by new inequalities and power relations, but they have the advantage of evading some of the traditional hierarchies of the artistic field. Instead of celebrating art as the creative outcome of exceptional minds authorized by artistic institutions, the open work demands the public’s involvement and never allows a work to be finished. It undermines the assumption of the artist’s extraordinary creative mind in favour of the erratic busy-ness of the bricoleur. The open work thereby dissolves the signatory power of the artworld: no need for official institutional authorization; the signature bears no value. One can only hope that, when suddenly everyone acquires the authority to decide on what to call art, the question itself will become meaningless. On that day, aesthetic exceptionalism will have passed away.

Imagine yourself back in Tate Modern again contemplating Rothko’s murals. Visualize the tantalizing vibrations of the red and black streaks on the canvas again. The Visual Studies professor comes up to you and breaks the spell of your enchantment. He tells you that you have been studying a copy. Now you can respond in a way that lives up to the spirit of the digital bricoleur, beyond aesthetic exceptionalism: “I do not care whether the painting is real or fake. I was just looking for something interesting to paint myself and put up on the wall of my living room.”

Notes

- 1Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the New Millenium (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 12.

- 2John Roberts, The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art after the Readymade (London: Verso Books, 2007); Maurizio Lazzarato, Marcel Duchamps ou le Refus du Travail (Paris: Les Prairies Ordinaires, 2014).

- 3I will not deal with these traditions here, but interesting perspectives can be found in, among others, Paul De Bruyne & Pascal Gielen, Community Art: The Politics of Tresspassing (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2011); Nico Dockx & Pascal Gielen, Exploring Commonism: A New Aesthetics of the Real (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2018).

- 4Maurizio Lazzarato, Signs and Machines (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2014), 173.

- 5Giorgio Agamben, The State of Exception (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 74-88; Arne De Boever himself has devoted a whole book to Agamben’s philosophy called Plastic Sovereignties: Agamben and the Politics of Aesthetics (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

- 6This initiative recalls especially anti-museum art like the projects of Daniel Buren, Maurizio Catellan, and Robert Filliou, or the recent non-exhibition from Evelin Brosi and Elvis Bonier in S.M.A.K. entitled “Get Lost.” See Mathieu Copeland & Balthazar Lovay, The Anti-Museum: An Anthology (Köln: Walther Koenig Verlag, 2017). I owe this reference to Arne De Winde.

- 7Other digital media, like Instagram or Twitter, provide their own opportunities for rendering the authority of the artworld inoperative. Especially meme culture and viral content allow for the infinite dissemination and variation of human creativity. Artists like Eveline Brosi rely on digital platforms for the dissemination of their work. However, memes and virality also hint at some of the downsides attached to this self-propelling proliferation of content on the internet. Once reactionary movements of the Alt-Right succeed in appropriating digital platforms for their own purposes, they can turn the latter into propaganda machines that aggressively disseminate not the values of human creativity and autonomy but subjugation to nationalist rhetoric. According to Hardt and Negri, the Alt-Right coopts emancipatory practices like internet communication and repurposes them for anti-emancipatory political projects. See Angela Nagle, Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right (London: ZED Books, 2017); Antonio Negri & Michael Hardt, Assembly (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 47-62.

- 8Alessandro Baricco, The Game (Turin: Einaudi, 2018), 169-170. My translation.

- 9Umberto Eco, The Role of the Reader (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984), 47-66.

c

clustered | unclusteredTales from Dafen

Winnie Wong

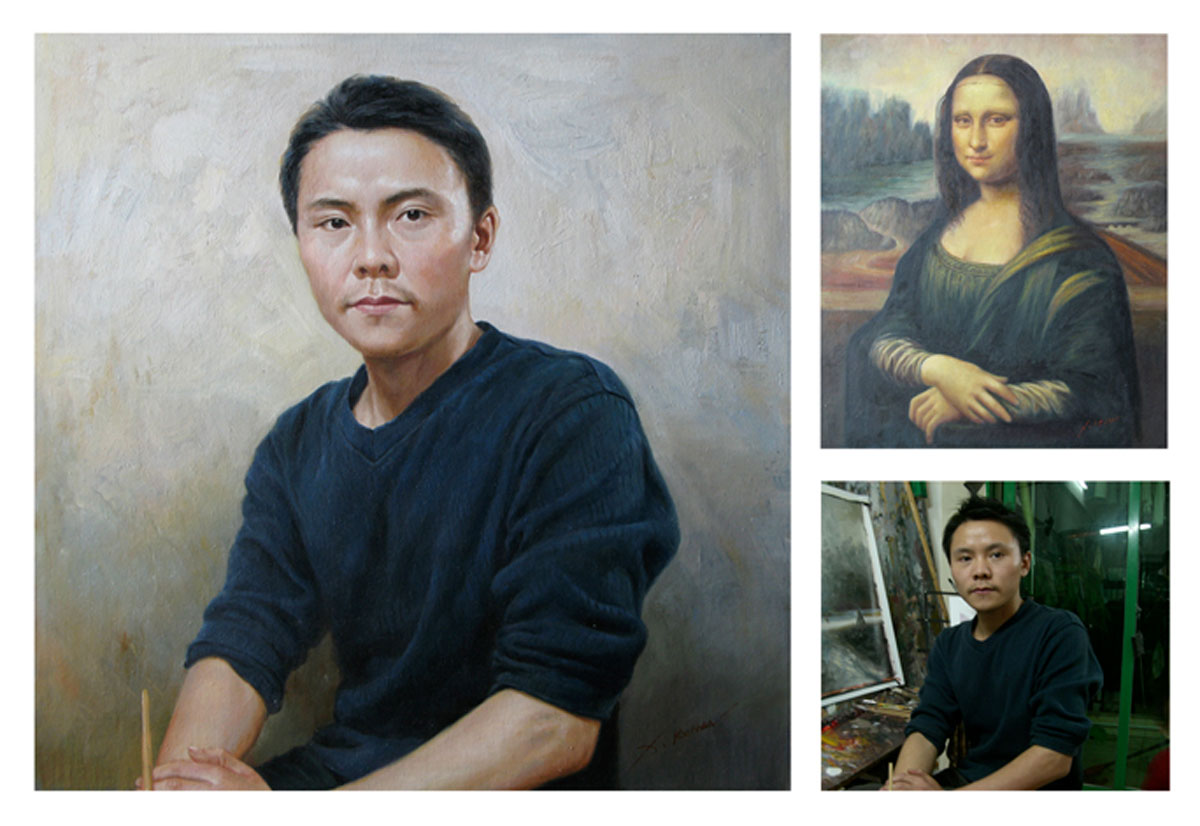

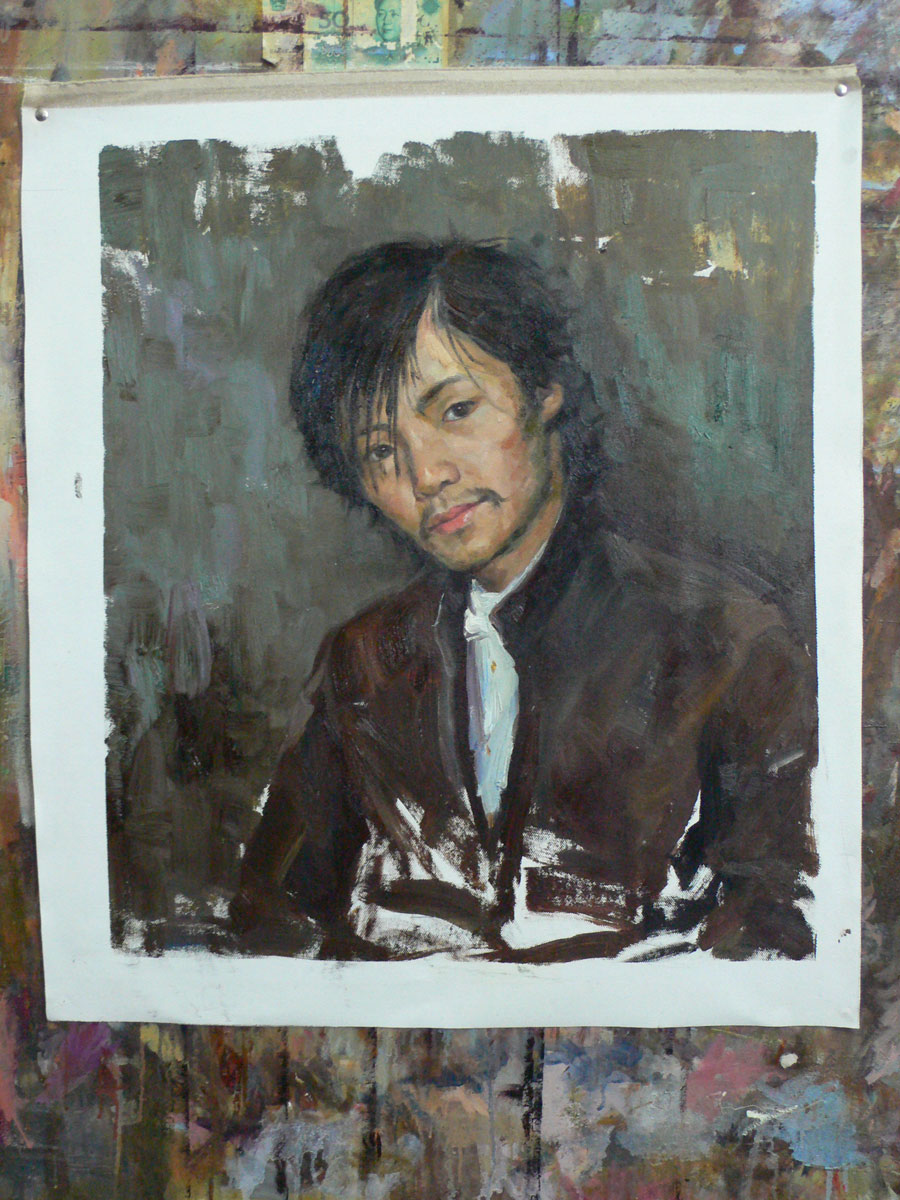

These tales are drawn from fieldwork conducted from 2008 to 2015 in Dafen village, China, the world’s largest production center for hand-painted oil paintings. All of the names, facts, and dates were true at the time of the telling, which in some cases spanned interactions over some months or years. Readers may refer to my book, Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (2014), for a scholarly account of Dafen village that strived to put such self-accounts into scholarly historical and artistic contexts. These tales, by contrast, record the stories of artists as they were narrated to me. They demonstrate how the most exceptionalist ideas of art are found anywhere, even in the most unexceptional places.

The Tale of a One-Way Street

Ms. Chen and Mr. Li own a little art gallery of their own in Dafen village. They met in Shenzhen a few years ago, when she came to work at an interior design company. He is an art academy graduate from Guangxi province. In many ways, he is her teacher.

She’s learning to paint from him, and learning about art. During the day, he goes out to different places to sketch and paint, while she minds their gallery. It’s just a small hallway that runs across the first floor of a building, under a stairwell. The walls are cement but whitewashed, the floorboards are polished wood, and they made their own signage out of driftwood. They named their gallery One-Way Street many years ago. Here they sell his paintings and drawings, in which he explores the mountains, the countryside, the sky.

But most customers who come into the store don’t understand their prices. They don’t understand that these paintings are unique and original, that they come out of a process of his going out to a place, spending time there, sketching, painting, and returning to his studio to create. They don’t understand that these paintings can be hung at home, but they are also for collecting. Few people understand this.

So Ms. Chen spends most of her days making her own paintings. For a while, she was employing pastel crayons to draw – or more like ‘dot’ – images on canvas. Some of these works were based on her memories from her village home in Sichuan province, others are of her daily life with Mr. Li. She paints their cat and their potted plants. The meal she cooked him the night before. The leftover beer bottles after he drinks with his friends. She paints him leaving the village in the morning to go out to sketch. She created a large series of these works, but she didn’t really sell any because she doesn’t care about selling. She’s just a student still. And her teacher is him. They don’t really care about money or what goes on in Dafen village because they only need each other.

One evening, one of their friends came by to give them a gift. It was a book he’d found in one of the used book stalls. It was called One-Way Street, and had some writings by a German philosopher. Their friend thought that since their gallery had the same name as the book, they might like it. She read it in her spare time. It was interesting enough. But she doesn’t really read anyways. She just wants to paint.

The Tale of Speedy Lai

C.W. Lai, overseas Chinese, was born in 1937 in Indonesia. When he was 16, he told his father that he wanted to return to the motherland to join Chairman Mao’s revolution, to help in constructing the great socialist society of the new China. So he returned to his ancestral home in Guangdong province, Meizhou village. He was one of Chairman Mao’s overseas returnee youths. Mao sent for them in ships, he put them in special schools, it was glorious to be part of the revolution. Lai took the examination for the Guangzhou Art Academy, but he was only put on the waiting list. That year, there was a fire in his village, he ran into the burning building to save the people in it. He was called a hero in the newspaper! But his father in Indonesia heard about this, and was so mad. He sent word that his son was to go to university right away.

So in 1958, Lai went to the Wuhan Institute of Physical Education. He became a sprinter. He was really good at running, really, really fast. Afterwards he stayed at the Institute and worked as the track and field professor. He taught there for nine years, even during the Cultural Revolution. In 1972, he smuggled his way into Hong Kong.

In the 1970s, there were painters everywhere in Hong Kong. Practically every street and alley of Tsim Sha Tsui had paintings for sale. He finally went back to painting, which was what he’d wanted to do all his life. He opened a gallery in Causeway Bay, called Riveria Gallery. It was in the Riveria Building next to the Excelsior Hotel, which is still there.

He first saw paintings painted entirely with a palette knife being done by a Vietnamese painter, so you could say that that man was his teacher. The other painter who painted like that used to work in front of the Hilton Hotel. Anyways, by watching them, he went home to make his own paintings, with entirely new compositions. Of course, back then, everyone painted fishing villages, the Hong Kong port, Peddar Street, junk boats, and so on.

But his own style was entirely new and different. He was the first to paint with a palette knife on canvas. And later he painted paintings entirely in blue, then in red. Only many years later did he hear that Picasso also had a “blue period” and a “rose period.”

Once there was a dealer who offered him 300 HK dollars for each junk boat painting, but only if he would paint 5,000 paintings in a year! Lai declined. If it was 2,000 paintings or so, over three years, then he’d have been willing.

By the 1980s, there was too much competition from the painters in the Mainland. By then, the price for a small 6 x 8 inch painting was only 3 Hong Kong dollars. Many people moved back to the Mainland, or they just changed jobs. Some of his friends switched to housepainting. “It’s even easier,” they said, “No thinking required!” So they painted the walls, instead of the paintings that hung on them.

In 1993, he closed his gallery, and went to Australia at the invitation of a magician, who became his manager. This was Peter J. Shield, who ran something called the World of Unexplained Mysteries. For two years, Lai gave live demonstrations of his painting technique and sold thousands of paintings. The Gold Coast Bulletin even wrote an article about him: “Speedy Lai Leaves Shoppers Stunned.” It described his eight-minute masterpieces.

Yes, over time, Lai had developed a technique that would allow him to paint a painting of a junk boat in the Hong Kong harbor in under 10 minutes. When painted on black velvet, he could do it in 5 minutes (because you don’t need to paint the background). He painted entirely with a palette knife and his Chinese nickname was “One Knife Lai.” Lai estimates that at this point in his life, he’s painted about 6,500 junk boat paintings.

Lai moved to Dafen village in 1999. Before moving there, he talked with a lot of the painters. He decided that, whatever their conditions, at least they had hope.

On the weekends, fans can find Speedy Lai painting at the Tsim Sha Tsui Harbor Walk in Hong Kong, where artists have to be approved by the Cultural Center managers to display their work to the public on the sidewalk. Those managers are horrible though. They have made up all sorts of rules to get rid of artists like him. First the artists had to pay. Then they could only show three of the same paintings at once. Then it was only one of each painting. Now they aren’t even allowed to sell them, just demonstrate.

One day, just one of his paintings will be worth more than a building. This is a fact. There’s nothing anyone can do about that. It’s a fact of history. Value accrues with time. His paintings already exist all around the world. They are already world famous.

The Tale of the Self-Portraitist

Xiao Keman was born in 1980 in the city of Xian. He attended the Normal University of his home province where he placed in advertising, but he had always wanted to be an artist instead. Though it was a crazy dream, in his senior year, he and several classmates organized themselves into a small group and convinced an art professor to hold painting classes for them. A few months later, the four art school graduates embarked for the city of Xiamen. There, they began to work as painters. Xiao soon specialized in figurative painting, a common specialty among university graduates that earned him higher prices for each painting than, say, impressionism or abstract painting.

In 2006, Xiao moved to the famous Dafen village, where he began working for Pix2Oils, a firm owned by an Australian expatriate named Bailey O’Malley and his Chinese wife, Little Red. Like all the companies in Dafen, Pix2Oils has a big gallery where they sell paintings, and it gives out painting commissions to a small group of painters. They all work and paint at home. Making a living as a painter is not easy, but in Dafen there are always orders, and so many painters. There are a lot of foreign buyers too, and curators and collectors who come around. So there’s always a chance to break through here.

One day in December 2006, the people at Pix2Oils asked Xiao to come by the gallery. They took a digital photograph of him, and asked him to paint it. Xiao agreed, and as usual, Pix2Oils paid him the usual price. In Xiao’s specialty, figurative painting, the price is determined by the size of the painting, the number of human figures in it, and the level of finish required. For this particular painting, a 72 by 72 centimeters single person portrait at standard quality, Xiao was paid about 200 yuan. The painting took one afternoon to paint, a few days to dry, and was delivered on time. Xiao figured the painting was part of an advertising plan to showcase the company’s painters.

A year later, a translator he knew, Liu Zhen, called him saying that there was an art historian from America who had seen one of his works, and that she wanted to talk to him about it. Xiao likes Liu Zhen – they’re from the same hometown – but he figured this would be a prank. It was April Fool’s Day after all.

They all met up in the plaza of the Dafen Museum of Art, and Liu Zhen’s friend brought out a photograph of that self-portrait he had painted a long time ago. He wondered where Liu Zhen and her friend they had found it. She said that the painting is being shown on the internet along with his photograph. She said that on that website it says the self-portrait was painted for two American architects who called themselves REGIONAL OFFICE, who said that when they ordered the painting, it gave him the unique opportunity to express himself creatively for the first time. Apparently, according to these architects, he had been paid a special price that reflected the international nature of his work. Xiao had never heard of these clients nor met them, so who knows why they were saying these ridiculous things. Then he remembered again that it was April Fool’s Day. So he told Liu Zhen and her friend that the whole thing just sounds like one big joke.

Sometime before he met these people, Xiao had painted a self-portrait. Just something he had dashed off because he felt like it that day. It’s not for sale.

d

clustered | unclusteredWorks of Infinite Correction

Stéphane Symons

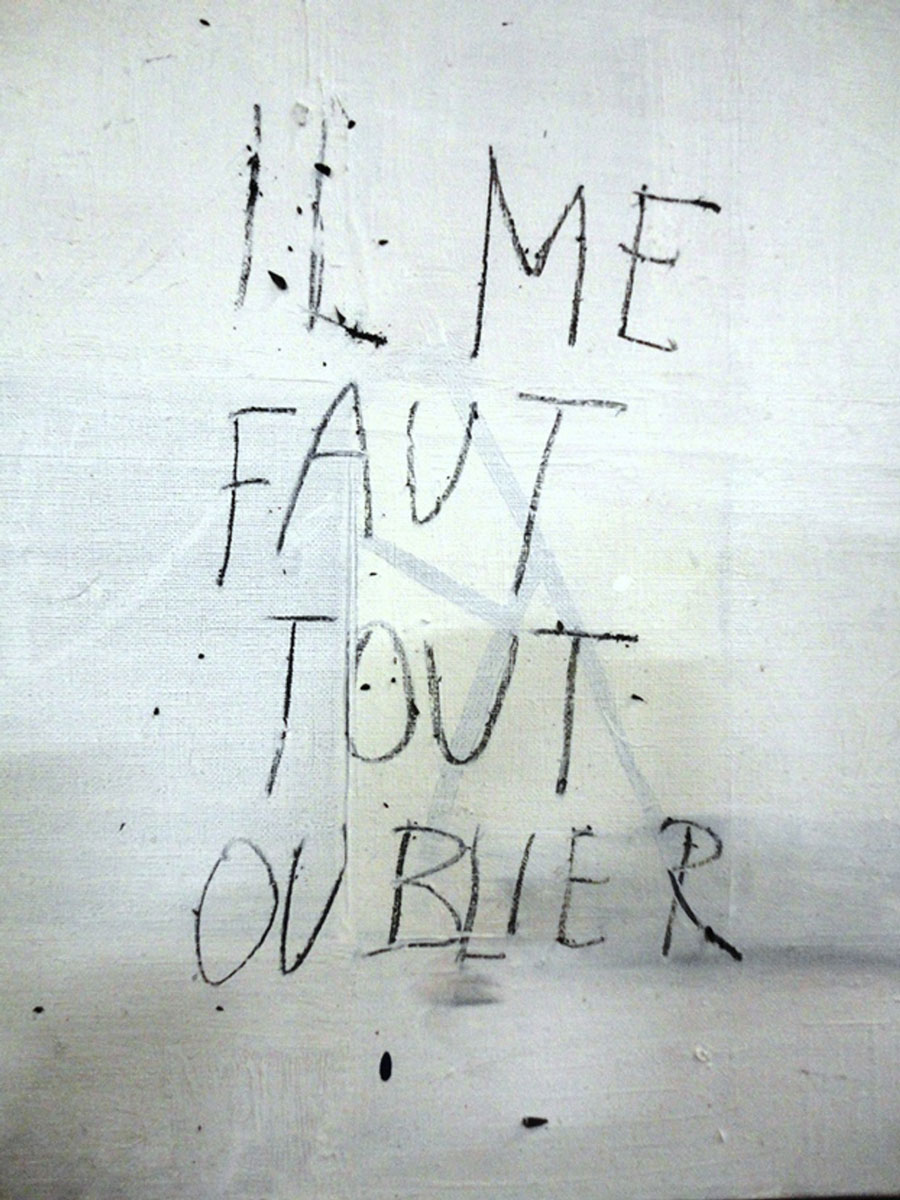

“Il me faut tout oublier.” These are the words that the Belgian artist Philippe Vandenberg wrote down or painted during the final years before his death, again and again, in charcoal on paper, or in oil on canvas. They are a violent outcry, an urgent command, an expression of distraught desire. But what exactly they so desperately seek to convey is hard to know for sure. There being, according to Umberto Eco, no “ars oblivionalis,” forgetting is after all no mental activity one can bring about at one’s own will or master step by step.1 For Vandenberg, disappearance and annihilation are the objects of his longings, rather than any specific activity, thing, or situation that we could relate to or bring before our mental eye. Moreover, the formula “Il me faut tout oublier” is penned in such a way that it forces human language to confront its limits. Composed in a child’s handwriting, it presents language to us less as a medium of communication than as a visual entity with distinct material and physical qualities. The series recalls Cy Twombly’s work which, in the analysis of Roland Barthes, looks “as if it has been drawn by his left hand.” Vandenberg’s words, too, put on display “what is clumsy, embarrassed”; they can be called a type of “gaucherie”: they topple the language of high culture and society, so certain of its truths and proud of its merits.2

In one of his essays, Vandenberg proclaims that he only “makes the next work to escape from the previous one.”3 For him “the creative process consists largely of destruction.”4 This brings Vandenberg in the company of the Swiss writer Robert Walser who, according to Walter Benjamin, wrote sentences that “make the reader forget the previous one” and the Afro-American jazz pianist Thelonious Monk who, in the words of Geoff Dyer, “played each note as though … every touch of his fingers on the keyboard was correcting an error and this touch in turn became an error to be corrected.”5 The inseparability of creation and destruction could mean that, perhaps, such art matters less as a type of representation or presentation than as a type of neutralization – what in the jargon of academic philosophy is called negation. Such works of art are not expressive of an inner certainty on the part of the artist, such as, for instance, his or her fluent mastery of a specific genre or instrument, or the firm conviction that what he or she is saying truly matters. To the contrary, these works of infinite correction are born from a deeply felt and all-consuming sense of discomfort, either self-proclaimed by the artist (Vandenberg) or ascribed to him by a critic (Walser, Monk). Their makers, it seems, want to cancel out the world in its current state, so that we can at least all get a chance to start over. It would be wrong to assume that this call for a new beginning results from the adherence, either explicit or implicit, to a specific goal or ideal for improvement. What grants such work their expressive quality is not their ability to recast our surroundings in newer and better terms, let alone to present hitherto unknown truths about them, but their power to suspend our ties to those surroundings for the briefest of moments: a sudden and much needed release from all the pains and strains that make our world, for far too many among us, an uninhabitable place.

The Weather without Exception

But what good can we expect from such a canceling out? Why does Vandenberg insist that such “[a]rt comforts us. Art heals people”?6 And why have Walser’s characters, according to Benjamin, indeed “all been healed”? Why did we always feel that “at the heart of (Monk’s) tune was a beautiful melody that had come out back to front”?7 For the artists I am considering here, the process of healing can only originate in a unsparing rejection of what has caused the pain in the first place. In the introduction to her recent collection of essays, Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, Olivia Laing draws attention to the connection that a specific type of artistic creation has to destruction. Framing this connection as a distinctly political and societal issue, she describes the years in which her texts were written as a succession of catastrophes: Brexit and Trump, Charlottesville and the Grenfell Tower, racist killings and the rise of political and moral conservatism. There is a by now worn out formula that defines a crisis so deep that all existing categories, be they political, moral, religious or epistemological, are deemed inadequate to usher forth a solution: the formula that the state of emergency has become the rule.8 “It was happening at such a rate,” writes Laing, “that thinking, the act of making sense, felt permanently balked. Every crisis, every catastrophe, every threat of nuclear war was instantly overridden by the next. There was no possibility of passing through coherent stages of emotion, let alone thinking about responses or alternatives.”9 In times of such radical upheaval, none of the artworks, novels and artists that are dealt with in Laing’s collection of essays, from Sally Rooney’s Normal People to Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick and from Jean-Michel Basquiat to David Hockney, can teach us any clear lessons, light the path ahead, incite a certain course of action, or, more simply perhaps, present us with scenes of unspoiled beauty. For Laing, such age-old artistic ambitions would not only be irrelevant and miscast but even improper as our world is faced with levels of complexity that defy easy solutions and momentary comfort. It is in the face of these political and social derelictions that she turns to artists who refuse to simply renew our trust in the society we built and, instead, grant us some time off from it: “What I wanted most, apart from a different timeline, was a different kind of time frame, in which it might be possible both to feel and to think, to process the intense emotional impact of the news and to consider how to react, perhaps even to imagine other ways of being.”10

If we seek a firmer grasp of the “different kind of time frame” that an artist can produce to feel and think through moments of deep crisis, it helps to first understand what he should not do. In Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism, the essay that provides the occasion for this reflection, Arne De Boever rejects the notion of the artist as a seer whose insight into the true state of the world would somehow be more accurate and profound than that of other mortals: “Briefly put, aesthetic exceptionalism names the belief … that art and artists are exceptional. … This line of questioning will focus on the sovereign figure of the artist as genius.”11 De Boever builds on Carl Schmitt’s insight that modern power is defined by the authority to proclaim the state of exception and thereby restore order. In that view, the modern sovereign ruler is the only person who can decide that a crisis is so threatening that all normal legislation should be suspended and replaced by emergency laws. For Schmitt, the modern sovereign ruler thus incarnates the sole force that remains untouched by a chaos that jeopardizes the survival of the polity as such: stepping in where every other political or juridical category fails, the modern sovereign’s judgments and decisions are deemed absolute.

Schmitt’s account of modern sovereignty is part of a political theology since, in his view, “(a)ll significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts.”12 This means that, on account of the absolute powers that are granted to him (the argument is deeply androcentric), the modern sovereign ruler should be considered the heir of a type of transcendence that, in a premodern, religious context, was derived from God. De Boever takes issue with the belief that, in today’s world, fraught by political and ideological polarization, it is the artist who has retained such a space of uninhibited thought and decisiveness. In such a view, artistic creation and aesthetic perception are marked by the unrestrained freedom and insight that can help us come to terms with moments of distress. Like Schmitt’s sovereign ruler, the artist is all too often believed to have qualities that somehow surpass the limits of other human beings. This, for its part, grants him a clearer view of the world’s shortcomings and might even strengthen him against some of its pitfalls. There is a great risk to the idea that, in the end, the position and activity of the artist are capable of withstanding the challenges and upheavals of society. In De Boever’s view, such illusions are symptomatic of an underlying skepticism about the capacities of “normal” human beings and the merits of democracy, and perhaps even of an obscure longing for an authoritarian ruler: “The unreflexive attachment to an exceptionalist politics-of-art-that-suspends often risk(s) being a secret promotional campaign … for the Schmittian politics of the state of exception.”13

Against Symbolic Exceptionalism

When the artist’s judgment and creativity are credited with nearly superhuman capacities, the danger of an aesthetic theology comes near. One could say that the artwork thus becomes the false pre-allocation of a supposed eternal truth, infallible judgment, or absolute wisdom. Rather than pointing to a concrete situation as something that can be changed, or inviting active engagement on the part of the viewer, such an artwork aspires to the status of a symbol (a term that is as deeply implicated in theological thought as sovereignty is, and that this section will develop to reframe De Boever’s critique of aesthetic exceptionalism): it presents itself as an entity that is “complete in itself” and seeks to overwhelm the viewer as an epiphany. Blurring the lines between aesthetics and theology is pernicious because in reality, no artwork can assert itself as a symbol without also participating in what the Italian philosopher Furio Jesi has called a “return to nothingness.”14 Contrary to common assumptions about symbols and symbolization, symbolic images are always marked by a certain emptiness: they do not receive their meaning from an external referent since these seemingly external meanings have always already been the result of symbols and symbolization in their own turn. A crucifix, to give an evident example, is the condition and not a mere outcome of the belief in Christ’s resurrection and the religious rituals that come with it. Symbols are constitutive of the meanings they supposedly embody.

When artworks proclaim the status of a symbol, they present themselves as self-legitimating, infallible, and unmistakable truths and no longer “call forth a different reality that exceeds them.”15 In thus blocking the path towards genuine understanding and the comprehension of a specific situation, an artwork that lays claim to this symbolic “nothingness” forecloses any genuine activity on the part of the viewer: critical assessments or subjective interpretations are above all inhibitions to the supposed powers of such artworks. For this reason, Jesi connects the symbol to silence and, ultimately, to death. A symbolic image manifests itself as the revelation of a truth that can be neither grasped nor contested by human language; as a consequence, its essence remains unspeakable, inspiring us to respond with awe and silence.