36 — February 2023

clustered | unclusteredReading Radio Stardust: On the Art of Music Video

Editors: Pieter Vermeulen & Arne De Winde

Video famously killed the radio star; what is less well known is that the stardust left in the wake of that killing has continued to enchant the world in the guise of music video. Launched into ambient ubiquity with the start of MTV in 1981, music video was part of the texture of the late-twentieth-century end of history; it survived that end and witnessed the return of history with its “post-televisual resurrection online” in the early twenty-first century.1 Always tainted by the suspicion of banality and the curse of brevity, music video has had a hard time occasioning sustained critical and scholarly attention; indeed, the very genre category “music video” (in the singular) may sound decidedly quaint in contrast to the plural “music videos”—a plural that seems to better fit the logics of mindless accumulation and indifferent multiplication that, for many, better fit this fatefully commercial and consumable form.

This cluster insists on the singular—on “music video” as an artistic genre in its own right. Capitalizing on the 2021 pandemic standstill’s eery capacity to force a reconsideration of the relation between the banal and the spectacular, the everyday and the glamorous, Collateral organized a series of online lectures that each responded to one music video. Cumulatively, these lectures (some academic, others artistic) testified to the capacity of the music videos to repay serious consideration. The contributions to this cluster rework some of the lectures in that series.

Insisting on the artistic integrity of this uniquely multimedial genre, for our contributors, means taking instances of the genre seriously as objects of sustained attention. That seriousness, for our contributors, also entails allowing the singularity of these instances to shape the form that the outcome of their attention takes here. The four contributions present four different forms of attending to music video in three different formats. Mathias Bonde Korsgaard’s audiovisual essay refuses to surrender to Weval’s mesmerizing “Someday,” and instead rigorously analyzes it as a carefully constructed audiovisual composition—a careful construction that the essay’s painstaking analysis inevitably ends up decomposing even as it reveals it. Jaap Kooijman’s audiovisual essay offers a comparison of two Sophie Muller videos shot during lockdown in empty London clubs; the contrast between the two clips—one showing the void, the other anxiously covering it over—showcases music video’s capacity to channel barely articulable social anxieties and desires. Dominique De Groen’s textual essay also operates through comparison; her juxtaposition of how Rina Sawayama’s “XS” and Evanescence’s “Everybody’s Fool” formulate anti-capitalist critiques within hypercapitalist structures interrogates the affordances and limits of a potential politics of music video. In Rana El Nemr’s contribution, music video (Kanye West”s “Runaway”) provokes an artistic response that takes the form of almost unbearably detailed visuals and uncomfortably abstract text. In their different ways, the four contributions demonstrate how music video counts as art.

Notes

- 1 Mathias Bonde Korsgaard, Music Video after MTV: Audiovisual Studies, New Media, and Popular Music. Abingdon, Routledge, 2017.

a

clustered | unclusteredAnalyzing Music Videos: On Weval’s “Someday”

Mathias Bonde Korsgaard

With this audiovisual essay, I have aimed to make up for two deficiencies in past scholarship: the lack of analytical methods in extant music video research and the lack of audiovisual essays as a format for music video research. It is striking that even while music videos “lend themselves to analysis […] there aren’t many analytical models to draw upon” (Vernallis 2019, 255). While this essay probably does not fully make up for this lack—it surely doesn’t provide a strict and reproducible “analytical model”—hopefully, it can function as a sort of crash course in music video analysis or at the very least give some guidance on where to start. The essay does not draw explicitly on extant music video scholarship, but it was indirectly informed by some of the key threads that have run through this research tradition. Of particular importance is the fact that in music videos “music comes first” (Vernallis 2007, 112), meaning that “videos (not surprisingly!) work more like songs than films” (Frith 1988, 143). Along these lines, music video analysis must always attend to both visual and musical matters—a seemingly banal observation, but one that has not always been adhered to in past analytical practice. As the field of music video research has continued to grow, many scholars have insisted on the audiovisual nature of the medium of music video. Of particular importance is Carol Vernallis’ book Experiencing Music Video from 2003 that argues for a parametric approach to music video analysis, focused on a range of different parameters (narrative, editing, space, color, texture, time etc.) with a constant concentration on the “deep connection between image and song in music video” (Vernallis 2003, 44). More recent endeavors of a similar bent include Brad Osborn’s Interpreting Music Video (2021), which provides a guideline for approaching both the visuals and the music in analyzing videos, as well as my own book Music Video After MTV (2017), where I insist that music videos work through both visualizing music and musicalizing vision.

My other aim with the essay was simply to provide one of the first scholarly audiovisual essays about music video. Surprisingly, these are few and far between, virtually non-existent (although Jaap Kooijman provides another example elsewhere in this cluster). This is all the more surprising because one would think that music videos are perfectly suitable for the specific kinds of analysis made possible by the audiovisual essay, especially given their shared audiovisual basis. That being said, making audiovisual essays about music videos is challenging precisely because of music video’s basis in music. While the rhythmicality of the music certainly provides certain inspiring possibilities for editing such an essay, it also risks imposing certain structures. In making this essay, I felt equally encouraged and restricted by the pulsating rhythm of the music: the incessant 4/4 feel of the music made it easy to create smooth transitions between different parts of the video (and even between the video and the live version of the same song), but in using voice-over, I frequently had to shape my sentences to fit into the musical progression (in other words, this is the closest I have ever felt to being an MC while working academically…). The use of voice-over has long been the subject of debate in scholarly discussions of videographic criticism, and I have to agree with Adrian Martin that it was something of a “mixed blessing” (Martin 2010) to use voice-over here, particularly because it is difficult to have voice-over and music simultaneously without the potential risk of one drowning out the other. On the other hand, with words also being an integral component in music videos (as addressed in the essay when I discuss the role played by the lyrics of the song), using voice-over still appeared as the obvious methodological choice.

Given my methodological ambitions, it is no coincidence that I ended up working on Weval’s “Someday”. On the one hand, I chose the video precisely because it is exemplary in demonstrating—or allowing the essay to demonstrate—why video analysis is highly complex and why adhering to the sum total of music-image-lyrics will often yield the most precise insights into the meaning of any given video. In other words, I chose this particular video because it is difficult: the lyrics are very sparse, the music somewhat repetitive, and the visuals function in a decidedly abstract and non-narrative way. Therefore, the analyst cannot resort to merely discussing what the video is “about”—instead, the proposed analytical approach is exactly to continuously take the interrelations between the three elements of music, image and lyrics into account. On the other hand, I cannot help but admit that I also chose the video for other less strictly academic reasons: frankly, I have been fascinated with the video since I first encountered it, perhaps also because I found it so hard to pin down. The elusive nature of the video intrigued me, and the effort I imagine that the director, Páraic McGloughlin, must have put into making it absolutely blows my mind. As such, the video is also exemplary in another admittedly more subjective sense: to me, it stands as an admirable video because the added visuals elevate the music into something which it cannot be on its own, revealing that the magic of any music video is how it is more than just the sum of its parts—indeed, something uniquely audiovisual.

References

- — Frith, Simon (1988), Music For Pleasure: Essays in the Sociology of Pop. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- — Korsgaard, Mathias Bonde (2017), Music Video After MTV: Audiovisual Studies, New Media, and Popular Music. New York & London: Routledge.

- — Martin, Adrian (2010), “A Voice Too Much”, De Filmkrant 31.

- — Osborn, Brad (2021), Interpreting Music Video: Popular Music in the Post-MTV Era. New York & London: Routledge.

- — Vernallis, Carol (2003), Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context. New York: Columbia University Press.

- — Vernallis, Carol (2007), “Strange People, Weird Objects: The Nature of Narrativity, Character, and Editing in Music Videos”, in Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones, eds. Roger Beebe & Richard Middleton. Durham: Duke University Press, 111-151.

- — Vernallis, Carol (2019), “How to Analyze Music Videos: Beyoncé’s and Melina Matsoukas’s ‘Pretty Hurts’”, in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music Video Analysis, eds. Lori Burns & Stan Hawkins. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 255-75.

Videos and films (by order of appearance)

- — Weval: “Someday” (2019), directed by Páraic McGloughlin, https://vimeo.com/328690392.

- — Weval: “The Battle / Someday live in Amsterdam” (2019), video by @vjlarsberg, Domnic van Buul, Emo Weemhoff and David Collier, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLOOmNeiQLk.

- — Chemical Brothers: “Star Guitar” (2001), directed by Michel Gondry, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0S43IwBF0uM.

- — Le Retour à la Raison (1923), directed by Man Ray.

- — Berlin – Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (1927), directed by Walther Ruttmann.

- — Talos: “D.O.A.M. (Death of a Muse)” (2018), directed by Kevin McGloughlin, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LNMw2e5kUT8.

b

clustered | unclusteredAnti-capitalist critiques and exploited doubles in Rina Sawayama’s “XS” and Evanescence’s “Everybody’s Fool” music videos

Dominique De Groen

1.

2020 may have been a dumpster fire of a year, but for pop music, it was undeniably the best year in a long time. Dua Lipa cemented her main pop girl status with Future Nostalgia, Lady Gaga saw a return to form with the 90s house music inspired Chromatica, and Miley Cyrus’ glam rock bangers on Plastic Hearts were a perfect match for her matured voice. One of the very best albums in this rich year was SAWAYAMA, the long-awaited debut album by Japanese-English artist Rina Sawayama, following up 2017’s acclaimed EP RINA.

Sonically, many of Sawayama’s songs hark back to the early 2000s, referencing not only the shimmering bubblegum pop and glossy R&B we instantly associate with that era, but also the nu metal and gothic rock in vogue at the time. While her sound in many ways encapsulates the top 40 sounds popular around the turn of the century, Sawayama manages to transcend mere nostalgia. A large part of what makes her music sound relevant today are the lyrics, which are deeply grounded in present-day concerns. Refreshingly, the album doesn’t really contain any songs about “traditional” pop music topics such as love or heartbreak. Instead, they tackle subjects like climate change (“Fuck This World”), friendships in queer communities (“Chosen Family”), intergenerational trauma (“Dynasty”), and racist micro-aggressions (“STFU!”).

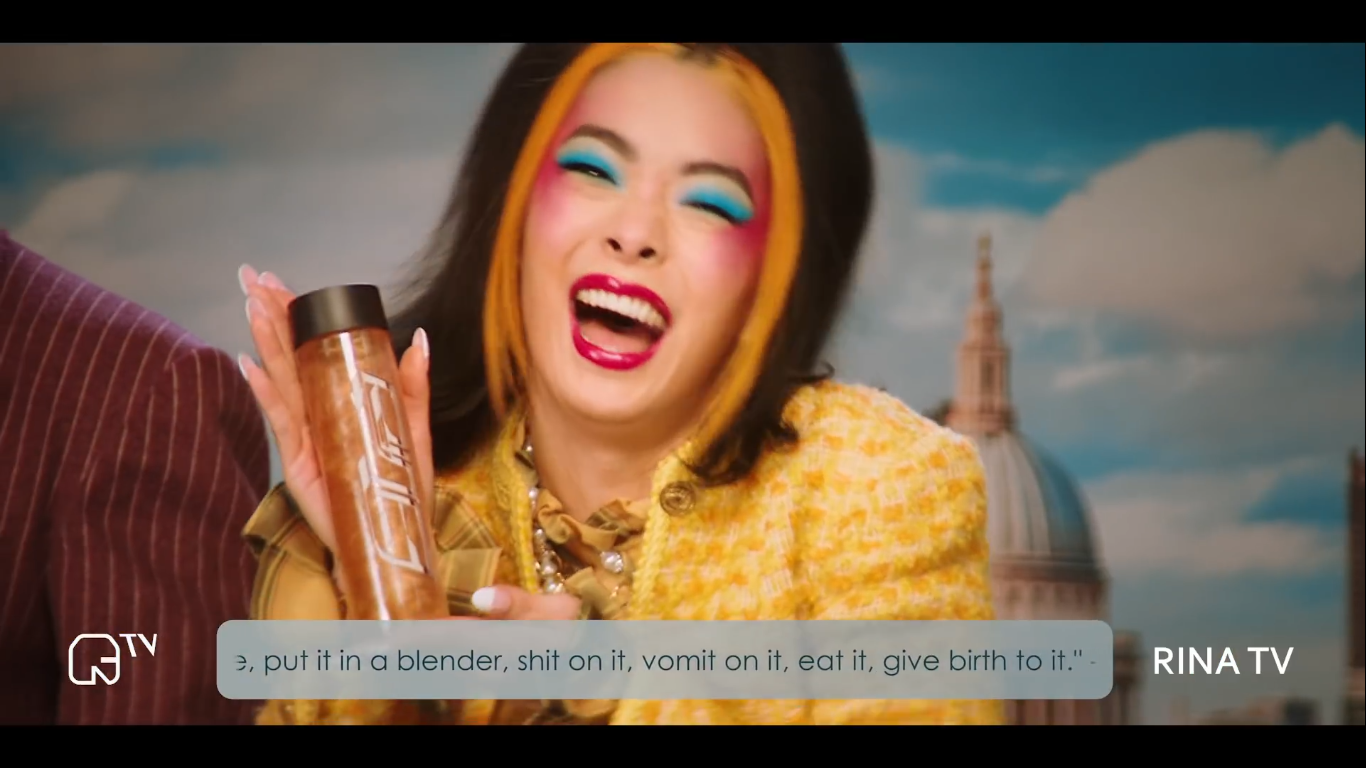

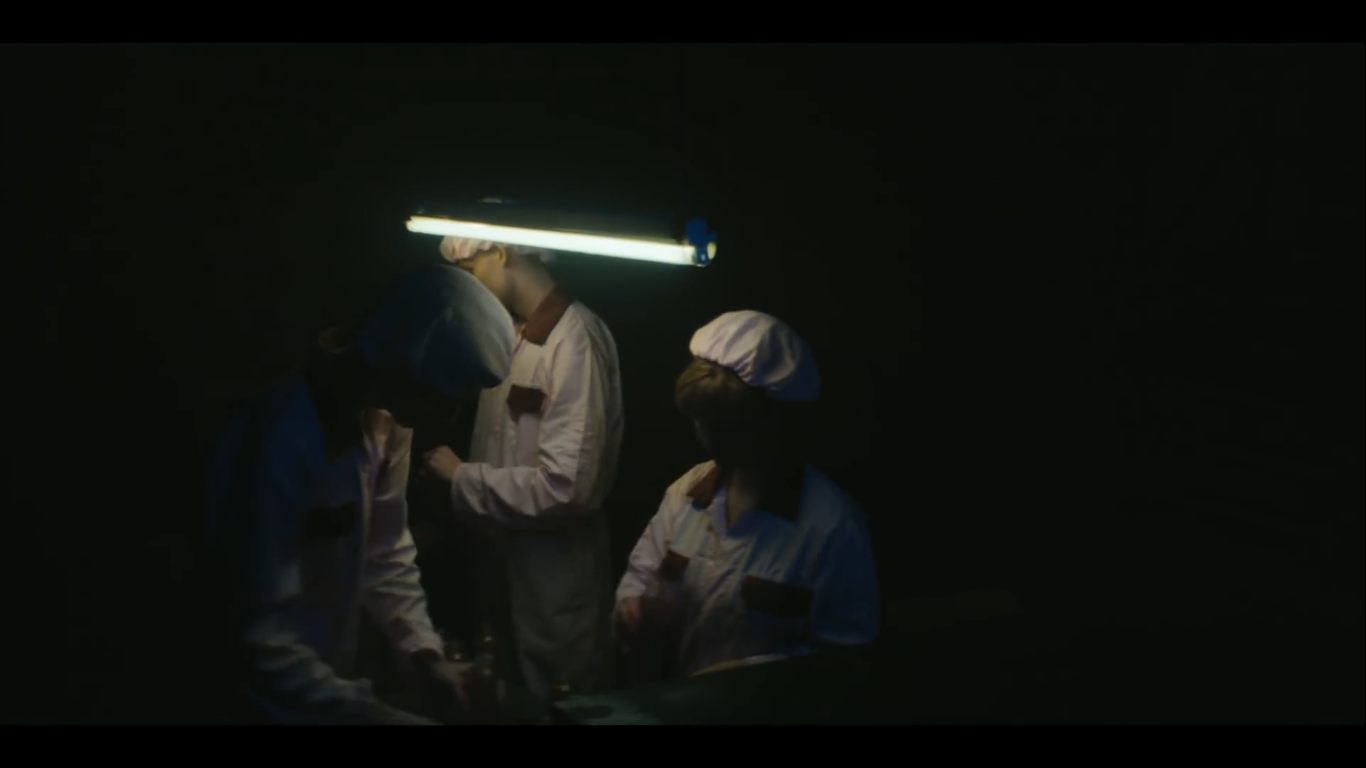

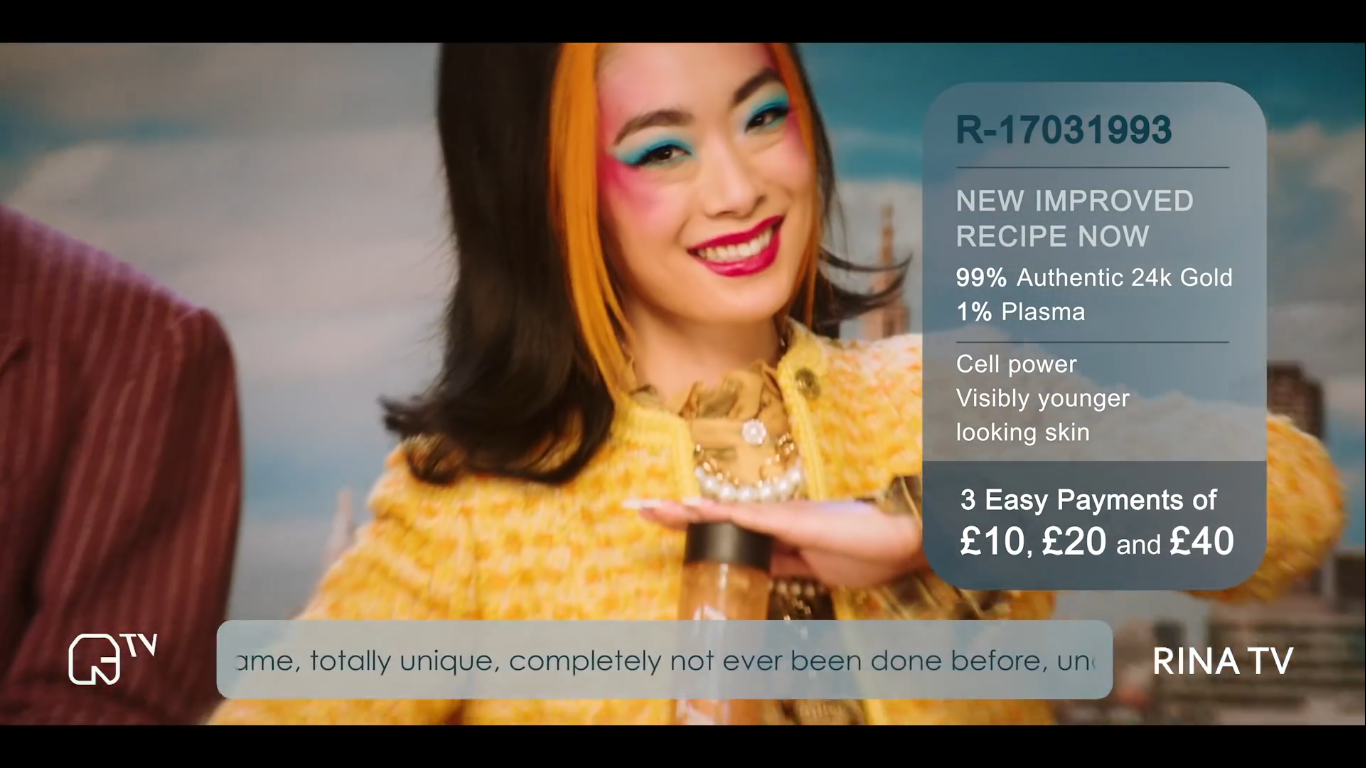

The album’s second single, “XS”, hones in on rampant consumer culture, with both the lyrics and the accompanying video (directed by Ali Kurr) denouncing overconsumption and capitalist exploitation. Sawayama plays a double role in the video, portraying both a manic, robotic saleswoman on a shopping channel, flogging bottles of a mysterious gold-infused drink named RINA to her audience, and a fantasy-like creature locked up in a laboratory, from whose body the golden liquid is forcefully extracted by scientists in lab uniforms. Sawayama herself has stated that this creature represents both the Earth, whose resources we are rapidly depleting, and exploited low-wage workers across the world.1 The casual way in which a consumer tosses one of the empty bottles into a pile of garbage at the end of the video reflects how rarely we think about the exploitation and suffering involved in the production of the material goods we take for granted.

Musically, the song’s verses are very reminiscent of the late 1990s, early 2000s bubblegum pop exemplified by Britney Spears’ or Christina Aguilera’s early careers. Throughout the song, however, the glossy pop sheen is regularly ripped to shreds by eruptions of heavy, nu-metal guitar chords. This musical juxtaposition reflects the contradictions Sawayama seeks to address in the lyrics and the video. In a press release, she described “XS” as

a song that mocks capitalism in a sinking world. Given that we all know global climate change is accelerating and human extinction is a very real possibility within our lifetime it seemed hilarious to me that brands were still coming out with new make-up palettes every month and public figures were doing a gigantic house tour of their gated property in Calabasas in the same week as doing a ‘sad about Australian wild fires’ Instagram post. (…) We’re all hypocrites because we are all capitalists, and it’s a trap that I don’t see us getting out of. I wanted to reflect the chaos of this post-truth climate change denying world in the metal guitar stabs that flare up like an underlying zit between the 2000s R&B beat that reminds you of a time when everything was alright.2

One of Sawayama’s own major musical reference points from that era, however, casts doubt on the statement that “everything was alright” back then. “Everybody’s Fool” was released in 2004 by Evanescence, a band that reached mainstream stardom by making the type of nu metal and gothic rock that Sawayama is so fond of quoting, both in “XS” and elsewhere on her album. The song’s iconic video (directed by Philipp Stölzl) offers a critique of the deleterious effects of consumerism and advertising, and while it approaches these issues from a very different angle than “XS”, its tone is easily as dark. The similarities between both videos are so striking that they seem unlikely to be a coincidence — although the differences are equally significant.

While both songs and videos criticise consumer culture, the perspectives from which they do so differ significantly. The “XS” video is rooted in Marxist theory. Not only is the creature symbolising the exploited underclass literally being sucked dry for profit, the opening line of the song’s second verse (“Flex, when all that’s left is immaterial, and the price we’ve paid is unbelievable”) also evokes Marx’ and Engels’ famous statement from The Communist Manifesto that “[a]ll that is solid melts into air.”3 The price Sawayama alludes to in this line could refer to the violence perpetrated against our fellow human beings working in sweatshops or Amazon warehouses, or against ourselves by tying our self-worth to luxurious belongings that inevitably leave us feeling empty and hollow. In an age of ecological crisis, moreover, this phrase inevitably evokes the climate catastrophe. This ecological dimension is completely absent in the Evanescence song and video, which might be a sign of the changing times—while climate change was of course talked about in the early 2000s, it was nowhere near the omnipresent mainstream topic it has become in recent years. “Everybody’s Fool” is more focused on advertising and celebrity culture, and more specifically on the toxic and corrosive effects they have on our mental health and our sense of self-worth. The erosion of self-esteem as a result of capitalist consumer and media culture is one of the topics alluded to by Rina Sawayama (“make me less so I want more”, she sings in the second verse), but for Evanescence it is the video’s central concern.

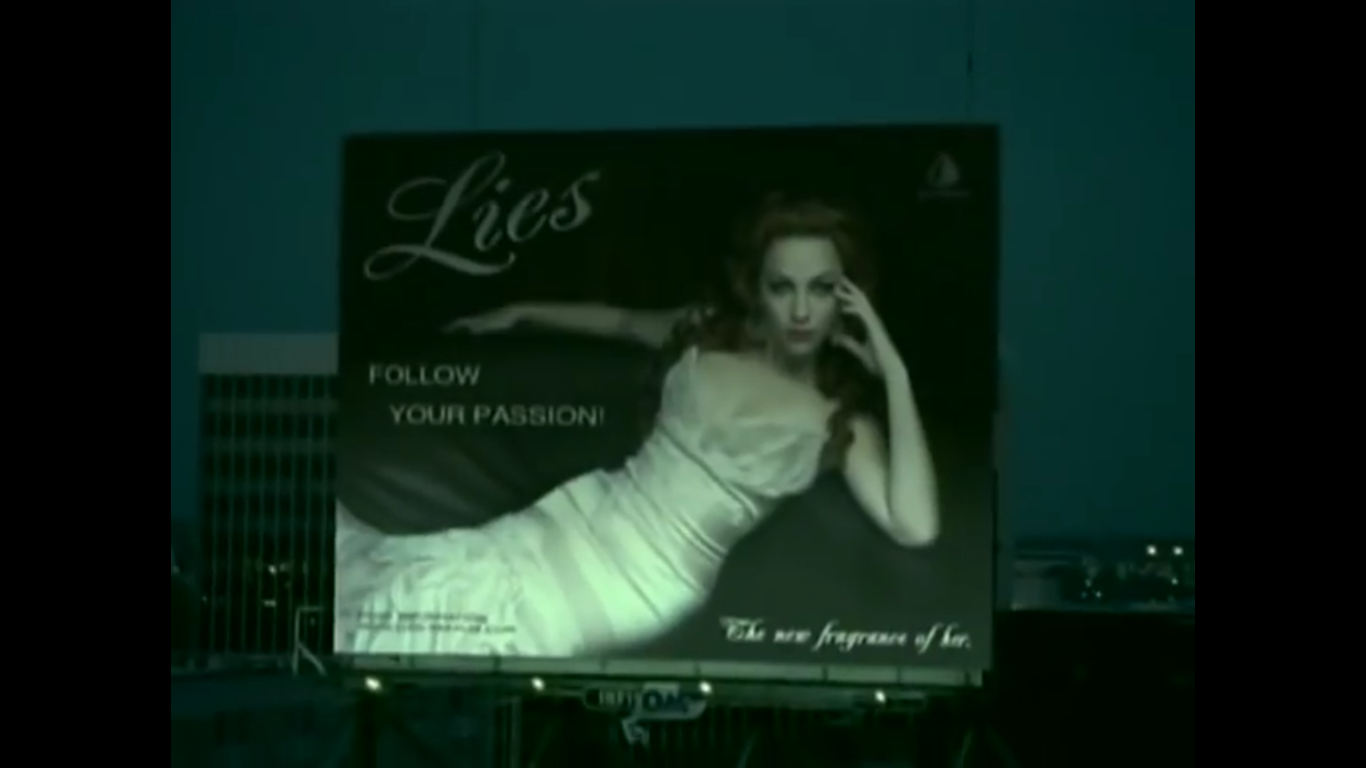

Evanescence singer Amy Lee plays a model and actress who advertises a brand subtly named Lies, whose slogan promises to allow you to “Be Somebody”.

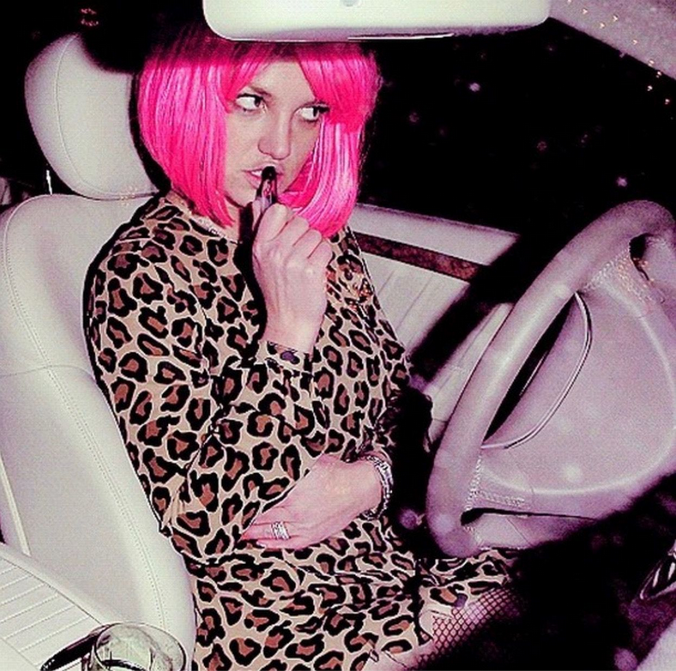

While the Lies logo graces everything from pizzas to energy drinks and from plastic dolls to fashion billboards, it is implied that Lee’s character is not really selling any particular product so much as an aspirational identity. It is equally clear that this identity is completely fake, a carefully constructed illusion without any basis in reality. This is not only communicated through lyrics like “more lies about a world that never was and never will be”, “you’re not real and you can’t save me”, and “you don’t know how you’ve betrayed me”, but also through the video’s visuals, which show the bleak reality behind the glamorous lifestyle the model’s campaigns conjure up. Amy Lee has stated that the song and the video are about stars like Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, and about how the perfect Hollywood images they embody actually conceal a very different and extremely toxic reality.4 This was years before Spears’ infamous mental breakdown, but in her case, at least, Lee’s assessment of the situation turned out to be more or less correct. In a sinister twist of events, after Spears shaved her head in 2007, she would aimlessly drive through L.A. wearing the exact same pink wig that Lee’s character in the video wears in the depths of her own depression induced by late-capitalist media culture.

2.

Sawayama and Lee both play double roles, externalising the fundamental contradictions at the heart of capitalist consumer culture. They are haunted by dark doubles of themselves. In “Everybody’s Fool”, this doubleness is immediately revealed; from the outset, the glossy commercials are consistently intercut and juxtaposed with the dreary, desaturated images of the model’s behind-the-scenes life.

In “XS”, in contrast, the creature in the laboratory is only revealed much later in the video, functioning more like a plot twist.

The “XS” video closely follows the structure of the song. The first verse, with its lyrics caricaturing a mindless consumer mentality (“I want it all, don’t have to choose”, “Cartiers and Tesla X’s, Calabasas, I deserve it”), is accompanied by images of Sawayama as a demented Stepford Wife trying to sell her RINA water on a shopping channel.

An early indication of the more critical direction the video will take is the opening scene, in which we see a courier (presumably precariously employed) delivering boxes of RINA water to the television studio.

This intro announces an awareness of the conditions of production and distribution underlying the glittering world of commodities—an awareness that frames the rest of the video.

In the second verse, as the lyrics morph into a direct critique of the mentality portrayed in the first verse, the video takes a darker turn: we see the first hints that something sinister might be going on in the laboratory, though we are not shown what it is yet, and the saleswoman reveals her robotic nature, starting to glitch and malfunction.

When we get to the bridge, the true nature and origin of RINA water are finally revealed, as we see a giant syringe being inserted into the shackled creature’s neck and fill up with golden liquid.

At the same time, the musical “zit” really explodes. While the metal guitars are unleashed, shots of the increasingly demented robot are rapidly intercut with shots of the angry and suffering creature in the laboratory. The video has switched genres by this point, mirroring the fluidity of the music: what started out as a slightly kooky and exaggerated but more or less realistic pastiche of a shopping channel has transformed into a sci-fi video containing robots, evil scientists, and a scaled, shiny-skinned fantasy creature with golden blood. In comparison, “Everybody’s Fool” is much more even in tone. There are few surprises, whether lyrically, musically, narratively, or visually. All the elements are present from the very start, and the two parallel realities are consistently juxtaposed throughout the video.

While the juxtaposition of different realities manifests itself differently in the two videos—in “XS”, the disparity is highlighted through surprise, while in “Everybody’s Fool” it is more consistently shown—the striking contrast between two visual worlds is an essential structural element in both of them. In “XS”, the bright, flashy, colourful television studio is opposed to the gloomy, dimly lit laboratory where the exploited creature is kept. In “Everybody’s Fool”, the glamorous, idealised commercials are juxtaposed with the drab, slovenly apartment building where the model lives, a world apparently drained of joy and colour (indeed, one wonders why a supposedly famous model would live in a place like this). Amy Lee has done something in this video that very few pop stars ever really do: she has made herself ugly. She looks pale, her hair and skin are greasy, she has dark circles under her eyes, her clothes are baggy and dishevelled. All life and colour seems to have been literally sucked out of her, just like the golden liquid from Rina Sawayama’s double. But in Amy Lee’s case, it is not a guy in a lab coat extracting her life force with a huge syringe. It is she herself: her glamorous, illusory double, who is, as the lyrics remind us, “not real”, but who is nevertheless sucking the real person who embodies her dry, like a parasite.

In one particularly depressing scene, the model is sitting in her apartment wearing a pink wig and staring at a plastic doll with the same hairdo, mimicking a commercial in which she both plays and advertises this doll.

She seems to be turning into her double, imitating the persona she was playing in the commercial—as if this fake character is, somehow, more real than her. As if this persona, and the glossy world it belongs to, is the original, instead of the copy. As if the only way for Amy Lee’s character to become real again, to become whole again, is to try to become this illusory persona, this fake double of herself. The parasitic double who has sucked the life out of her is now trying to sell it back to her. This, of course, is precisely the point the song seeks to make about the basic mechanisms through which advertisements operate: to quote Rina Sawayama in “XS”, they “make [you] less so [you] want more”.

The copy becomes more real than the original, usurps it, and the “original” is reduced to imitating the copy. Or, perhaps, there is nothing but a copy, without an original. This is how Jean Baudrillard describes the concept of the simulation: “the generation of models without origin or reality: a hyperreal”.5 Here, the map precedes the territory, it even shapes the territory, rather than the other way around. Baudrillard calls this the “precession of simulacra”:6 the idea that the imitation comes before, and is more real than, the thing that is being imitated. We can see this in the way real life increasingly anticipates, and is influenced and shaped by, representations of it on social media—with phenomena like selfie dysmorphia driving people to get plastic surgery to resemble filtered or FaceTuned versions of themselves. In the video for “Everybody’s Fool”, which preceded the social media age, this phenomenon takes a different form: a model turning into the character she plays in a commercial.

3.

The double, according to Freud, is an instance of the uncanny or das unheimliche. The uncanny signifies a deep sense of unease experienced when the world we inhabit, the things that are familiar to us, and even our very selves suddenly seem strange and alien to us. Freud describes it as “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar”.7 The uncanny stems from something that is deeply familiar to us, but that we have forgotten, or tried to forget, to suppress. When it suddenly and unexpectedly returns, in a distorted shape, it becomes frightening and unsettling. The double is uncanny because it signals the return of the repressed: a repressed version of ourselves, perhaps, or a repressed Other—in fact, the uncanny blurs the boundaries between self and other, revealing, as John Jervis writes, “traces… of the other in the self”,8 making the self fundamentally strange. The double is a revenant: something that returns. Something that we have tried to kill, but that refuses to stay dead. We are haunted by that which we have tried to repress, and by haunting us, these doubles remind us that beneath the surface of the here and now of our familiar world, for instance the world of luxury goods and commodities, there lurks another reality, an invisible reality—or rather, a reality we are trying hard to forget.

The doubles in these videos—the version of Rina Sawayama shackled in the laboratory, the model spiralling into depression in her apartment—are the suppressed Other of consumption. They represent the price we pay for everything we have accumulated—a price that, as Sawayama sings, is “unbelievable”, and that we therefore try to deny or ignore, to drown in cognitive dissonance. But in the form of these uncanny, restless doubles, this Other bubbles back to the surface, just like the metal guitars rising up from beneath the shimmering poppy surface in “XS”, like an angry zit just below the skin of the present. These doubles represent the dark twin of progress, the shadow of prosperity, the unavoidable and gruesome flipside of the narrative of glamour and opulence that the model’s glossy images and the TV saleswoman are trying to sell. And try as we might, these shadows refuse to be denied.

4.

Can we, then, interpret these pairs of doubles as representions of the exploiters and the exploited? Such a reading is tempting in its simplicity. We could certainly argue that the model’s public persona and the TV saleswoman profit from the suffering of their double. Their modus operandi is parasitic, almost vampiric. The way they drain the life force and even the blood from their doubles can be read as a visualisation of a Marxist account of the capitalist extraction of surplus value from workers. In Das Kapital, Marx repeatedly writes that labourers are literally sucked dry by capital, that they are robbed of their vitality, their life force. In a capitalist production system, individual survival depends on selling one’s life energies to people on the market. Most of us are not selling a product we have made; the product we are selling is ourselves, our energy, our mental and physical capacities, our limited time on this earth. Marx even compares capital to vampires: “Capital is dead labour,” he writes, “that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”9 The worker is victim to this “vampire thirst for the living blood of labour”,10 and “the vampire will not lose its hold upon him so long as there is a muscle, a nerve, a drop of blood to be exploited.”11 The imagery of blood-sucking vampires is omnipresent in Das Kapital. In this context, it would make sense to view the robotic saleswoman and the glamorous model in the commercials as the vampiric forces of capital, draining their doubles, who represent the exploited underclasses, of their life substance, or even their literal blood. The gold infusion in “XS” even promises to make the drinker look younger, suggesting that the life force extracted from the creature is transferred to the consumer in a very literal sense.

And yet the relationship between the doubles is more complicated than this simple exploiter-exploited-dichotomy would suggest. At the end of the “XS” video, the robotic saleswoman is herself tossed into the trash, discarded along with the boxes in which the RINA water was delivered, and thereby revealed to be as disposable as the product she was advertising. She, too, has been used up.

In “Everybody’s Fool”, of course, the model’s public persona is really the same person as her suffering double. They are two sides of the same coin. While it may appear as if she is fooling everyone else, it turns out, in the end, that she, too, is being duped. In the first three choruses, Amy Lee sings, “You know you’ve got everybody fooled” and “somehow you’ve got everybody fooled”. By the final chorus, however, this has changed into, “Somehow now you’re everybody’s fool”.

It seems the saleswoman and the model have themselves been betrayed by the system that seemed to serve them. Does this simply mean they are in turn being exploited by someone higher up the chain, and that the “true” exploiters remain out of view? On one level, this is undoubtedly the case: there is always someone higher up the chain. But perhaps the deeper point is precisely that there are no “true” exploiters we can point to in any straightforward way. The doubling of both Rina Sawayama and Amy Lee points to the fundamentally split nature of life and identity under capitalism. All of us, the videos seem to suggest, embody these two sides: in this system most of us are to varying degrees both exploiter and exploited. Even the Amazon warehouse worker has to consume food or clothes for the production of which others have suffered. That is not to say that we all embody both aspects in equal measures; the model advertising a fashion brand obviously does not occupy the same position in this complex web of relations of exploitation as the person stitching those clothes together in a factory in Dhaka. But whatever the precise proportions may be, we are all, to some extent, double. All exploiters are emanations of a system in which all of us are caught up.

5.

While these doubles can be interpreted and theorised in different ways, they are also clearly rooted in a common pop music video device: the star playing multiple characters or personas. Someone who has done this throughout her career is the star who inspired “Everybody’s Fool”: Britney Spears. Britney started doing this in her video for “Lucky”, which is about a famous, beautiful, young starlet called Lucky, who, underneath all the glitter, glamour, and universal adoration, is lonely and deeply unhappy—very much like Amy Lee’s character in “Everybody’s Fool”, which was released several years later. “She’s so lucky,” Britney sings, “she’s a star, but she cry, cry, cries in her lonely heart, thinking, if there’s nothing missing in my life, then why do these tears come at night?” In the video, Britney plays both the glamorous but unhappy starlet, and a more casually dressed, down-to-earth, girl-next-door version of herself, who hangs around in the background, observing the star but remaining unseen, clearly feeling sorry for her glamorous double but ultimately unable to intervene.

This is the first in a long row of doublings and splittings in the course of Britney’s music video career: she plays multiple versions of herself in the videos for “Toxic” and “Womanizer”, she destroys a clone of herself in the video for “Break The Ice”, and she fights herself in the video for “Hold It Against Me”.

One artist who has recently taken this trope even further is Taylor Swift, especially in her video for “Look What You Made Me Do”, which comments on the way she has been mercilessly vilified and misrepresented in the media. In “LWYMMD”, Swift provides a meta-narrative commentary on the practice of embodying multiple personas in music videos. She plays many different versions of herself, mostly based on different images she has assumed throughout her career—in past music videos, stage performances, or other public appearances. In the video’s coda, all these clones are gathered in a line-up and start arguing among themselves, each one trying to control the narrative about Taylor Swift and referring to various media controversies from the past decade.

Swift, then, takes the common trope of the star playing different versions of herself in a video, and magnifies it in order to ridicule the exaggerated media narratives that have been constructed about her. She reminds us that we do not know who the “real” Taylor Swift is; she has been buried beneath all these different versions of herself that have accumulated in the course of her career.

Sawayama and Evanescence also play into another music video trope: the presence of not only several different versions of the singer, but also of several diegetic levels, different levels of narrative representation. Carol Vernallis distinguishes three such levels: “performance space, story space, and televisual space”.12 Taking “Lucky” as an example, the story level consists of the scenes in which Britney plays Lucky and the girl-next-door shadowing her, and the performance level is that in which Britney-the-singer sits on a golden star and performs the song, commenting, like a narrator, on the events unfolding on the story-level.

In rock videos, the story-scenes might be intercut with shots from the performance-level where we see the band playing on stage, in a garage, or on a windswept plain. Additionally, many videos also feature a televisual level; a television screen might be beaming images of the artist performing the song into the story-level, causing these different diegetic spaces to bleed into each other, these different realities to fold in upon themselves.

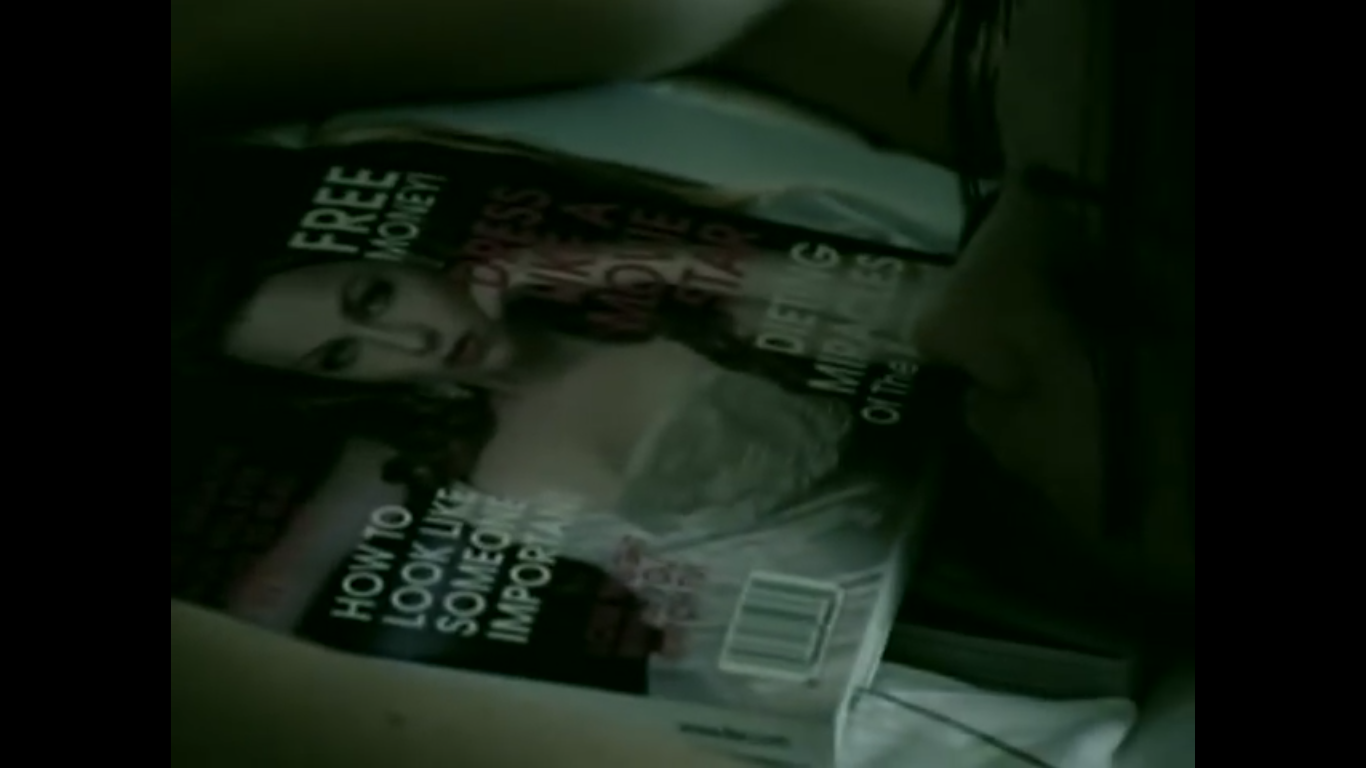

This is also the case in “XS” and “Everybody’s Fool”. Both the glamorous model and the TV saleswoman invade the dark, depressing spaces inhabited by their exploited doubles. In the Evanescence video, the conduits enabling this infiltration are a fashion magazine lying around in the apartment, and a giant billboard right outside the window; in Sawayama’s, it is a television screen in the laboratory.

These intrusions suggest that even within the narrative world of the video, the glamorous doubles and the worlds they inhabit are themselves fictional, less real than the shadow-worlds of their dark doubles. Even within the universe of the video, they only exist in a mediated form, as images, fictions on a screen or in a magazine. This, of course, runs counter to my previous comments on the copy usurping reality. But that seeming contradiction is precisely the point. It becomes difficult, perhaps impossible, to tell which of these worlds, if any, is more “real” than the other; this always remains ambiguous, an inextricable tangle.

In “Everybody’s Fool”, the only interaction the depressed version of Amy Lee’s character has with other humans is during a scene in her building’s elevator, when two girls recognise her from her commercials and start mocking her, saying that she looks much older than she does on-screen.

Her on-screen persona, then, is ultimately the point of reference, mediating any interaction she has with the outside world, and could in this sense be seen as the more “real” of the two. In “XS”, the world of the sales channel is at least somewhat grounded in reality by the delivery driver in the beginning and the consumer tossing the bottle into the trash at the end. The creature in the laboratory, on the other hand, whose appearance belongs to the visual language of sci-fi or fantasy, could conceivably be read as a nightmarish dream sequence or hallucination.

It is never quite clear, then, on which narrative level we find ourselves.

Nor is it ever completely clear who, exactly, is speaking the lyrics. The position of the speaker always remains more or less ambiguous. As E. Ann Kaplan, in a discussion of Madonna’s “Material Girl” video, has pointed out, such “ambiguity of enunciative positions” is common in music videos.13 This issue is especially glaring in “XS”, where the speaker’s perspective seems to shift between the first verse and the second. Is the saleswoman singing the first verse, and the creature in the laboratory the rest of the song? Is it the star, Rina Sawayama, who is speaking from an all-knowing ironical perspective? Is it perhaps someone watching the sales channel and commenting on it? And is the model in “Everybody’s Fool” mocking herself, or is she attacking an invisible exploiter? Are we listening the voice of some anonymous critic who remains out of view? Or is it Amy Lee, singer of Evanescence, who is voicing her opinions?

6.

Further complicating these ambiguities is the medium through which these critiques of capitalism and of media and advertising culture are presented to us. Whichever way you look at it, commercial pop music videos are first and foremost marketing tools, vehicles for promoting a song or a star. Perhaps injecting some kind of anti-capitalist message into them is a way of subverting them, of using these structures for undermining the ideology they represent—but even so, they still participate in the late-capitalist culture industry and, ultimately, cannot avoid strengthening it. As Theodor W. Adorno pointed out long ago, any criticism of the capitalist system voiced within the cultural structures of that system is immediately reincorporated—“every negative counter-instance”, every form of criticism or resistance instantly absorbed “by an omnipotent reality”.14 This results in an interesting tension. The way the RINA water and the Lies pizzas are advertised in these videos may very well be a knowing parody of the inescapable and aggressive product placement in contemporary music videos, but at the same time, we, the viewers, are still being sold something—or are being sold, full stop.

In this respect, we need to keep in mind the very different contexts in which each of these videos was initially consumed. “Everybody’s Fool” was released a year before YouTube was created, reaching its audience via music video channels like MTV, where it was surrounded by the type of content it was criticising: “Everybody’s Fool” might have been preceded by the hyperglamorous, sexualised video for Britney’s “I’m A Slave 4 U” and followed by Beyoncé’s “Naughty Girl”, or by one of the frequent commercial breaks. The “XS” video, on the other hand, is primarily consumed via YouTube, whether on their website, in their app, or embedded in a different environment, like a social media feed or an article on Pitchfork. These distinctive contexts might go some way towards explaining the different approaches the videos take to the issues they address. YouTube arguably affords artists greater creative freedom than MTV, because there is no central authority deciding which videos get played. Anyone can upload whatever they want, as long as it conforms to the terms of service. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that Sawayama’s critique of consumerism is both more grotesque and more explicitly anti-capitalist than Evanescence’s. Not only have mainstream artists become increasingly politicised in the post-Trump age, the age of online streaming also offers more space for niche content and for (radical) critiques of the status quo than network television. While it is certainly possible to draw comparisons between the two videos on a textual level, the creative choices these artists faced, and the scope of political commentary they could express through their work, were fundamentally shaped by the platforms on which their videos were distributed.

YouTube might afford more creative freedom, but its commercial logic is at the same time more ruthless and sophisticated than MTV’s ever was. Like MTV, YouTube makes its profits from advertising, but it goes several steps further: it gathers data about our viewing habits and, based on the type of content we watch, the algorithms create profiles that determine the kind of targeted advertisements we will see—both on YouTube and other sites or platforms owned by Google. These music videos, then, perform several commercial functions: promoting an album, getting us to devote substantial amounts of time watching ads, and, in the case of YouTube, forming part of a data mining operation. Both for MTV and for YouTube, we, the viewers, are the product, delivered up to advertisers. We may be watching these videos for free, but we can be sure of one thing: money is being made somewhere. The golden fluid being extracted is our time and attention.

7.

These two videos remain in many ways deeply ambiguous, offering no clear-cut resolutions to the questions they pose and the tensions they explore. At the end of “XS”, the robot might be broken and discarded, but we know the cycle will continue: there will be a new robot, and then another one, and then another one. The video for “Everybody’s Fool”, meanwhile, ends more or less in the same way it began. At the climax of the song, Amy Lee’s character attacks her own reflection, the symbol of the fake image that has been terrorising her, but this doesn’t seem to produce any substantial change beyond a shattered mirror. The video simply ends with her sitting in her bedroom, staring out of the window. For all we know she is about to head off for another day on set, ready to continue the cycle.

These anti-capitalist critiques, produced and distributed within hypercapitalist structures, pose interesting questions, not only on a narrative and thematic level, but also by their very existence. However, they provide no real answers, because how could they? They are themselves double, split—just like all of us watching them are.

Notes

- 1 “Rina Sawayama Shares Tongue-In-Cheek ‘XS’ Video”, DIY Mag, 17/04/2020, https://diymag.com/2020/04/17/watch-rina-sawayama-xs-video.

- 2 Allison Hussey, “Listen to Rina Sawayama’s New Song ‘XS’”, Pitchfork, 02/03/2020, https://pitchfork.com/news/listen-to-rina-sawayama-new-song-xs.

- 3 Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, trans. Samuel Moore, ed. Gareth Stedman Jones (London: Penguin Books, 2002), p. 223.

- 4 KRT, “Evanescence looks to future”, The Age, 30/07/2004, https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/music/evanescence-looks-to-future-r20040730-gdycsr.html; Corey Moss, “Evanescence’s Amy Lee Hopes To Get Into Film, Rages Against Cheesy Female Idols”, MTV News, http://www.mtv.com/news/1488307/evanescences-amy-lee-hopes-to-get-into-film-rages-against-cheesy-female-idols.

- 5 Jean Baudrillard, Sheila Faria Glaser (trans.), Simulacra and Simulation (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994[1981]), p. 1.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Sigmund Freud, Alix Strachey (trans.), “The ‘Uncanny’”, in James Strachey (ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Vol. XVII (London: The Hogarth Press, 1955), p. 220.

- 8 John Jervis, “Uncanny Presences”, in Jo Collins & John Jervis (ed.), Uncanny Modernity: Cultural Theories, Modern Anxieties (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), p. 12.

- 9 Karl Marx, Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production, Volumes 1 & 2 (Ware: Wordsworth Classics of World Literature, 2013), p. 162.

- 10 Ibid., p. 178.

- 11 Ibid., p. 206.

- 12 Carol Vernallis, Experiencing Music Video: Aesthetics and Cultural Context (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), p. 10.

- 13 E. Ann Kaplan, Rocking Around the Clock: Music Television, Postmodernism, and Consumer Culture (New York & London: Routledge, 1987), pp. 119-26.

- 14 Theodor W. Adorno, ‘The Schema of Mass Culture’, in Theodor Adorno & J. M. Bernstein (ed.), The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture (London & New York: Routledge Classics, 2001), p. 77.

c

clustered | unclusteredDancing at the Empty Discotheque:

Two retro-disco music videos shot during COVID-19

Jaap Kooijman

In an article published in The Guardian on 17 December 2020, Alexis Petridis proposes an explanation why retro-disco songs in general, and Kylie Minogue’s DISCO album in particular, are so popular during “the strangeness” of COVID-19:

As a genre, disco is lavishly escapist, but the best of it invariably comes with a curious undertow of melancholy. It is music that celebrates the transportive hedonism of the dance floor without ever entirely forgetting that there is something out there you’re keen to be transported from.1

Obviously, during the COVID-19 lockdowns, the dance floor was not located in the closed clubs but in people’s own homes. The two music videos of retro-disco songs that I discuss in this audiovisual essay return to the club’s dance floor, yet in noteworthy different ways: while one presents an escape from COVID-19, the other reminds us of the devastating effect that the lockdowns have had on club culture.

Kylie Minogue’s music video “Magic” was released on 24 September 2020; Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s “Crying at the Discotheque” on 27 October, one month later. The music videos have much in common. Both are videos of retro-disco songs, shot in empty clubs and venues in London during the COVID-19 lockdown. “Magic” was shot in the London club Fabric, while “Crying at the Discotheque” was shot at seven different London clubs and venues: St Moritz, Omeara, Bush Hall, Heaven, Clapham Grand, Apollo Theatre, and the O2 Arena. Both are performed by popular female pop singers. Both in sound and image, the music videos not only refer to these performers’ own retro-disco successes at the turn of the century, but also to 1970s disco culture. “Magic” is an original composition; “Crying at the Discotheque” is a cover of a 2000 hit single by the Swedish Eurodance group Alcazar, which uses a sample of the 1979 French disco song “Spacer” by Sheila and B. Devotion, composed by Nile Rogers and Bernard Edwards of Chic.

Another similarity is that both music videos were directed by Sophie Muller, one of the most prolific yet understudied music video directors. During the last four decades, Muller has directed more than 300 music videos, including works for Annie Lenox (both solo and with Eurythmics), No Doubt, Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, Maroon 5, and many others.2 She has directed all of Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s videos so far and several videos for Kylie Minogue. Quite surprisingly, there is little scholarly literature on Muller’s work. Prominent music video scholar Carol Vernallis only mentions her once; not without irony, she merely states that Muller is “underrepresented.”3 This audiovisual essay focuses on just two music videos, and therefore cannot do full justice to Muller’s oeuvre, but it hopes to stand as an invitation to further exploration of her work.

This comparative audiovisual essay recognizes the similarities between the two music videos, but most of all highlights one significant difference. While “Crying at the Discotheque” emphasizes the club’s emptiness, “Magic” conceals it. The audiovisual essay focuses on the different techniques used, particularly where cinematography and montage are concerned, to either emphasize or conceal the emptiness of the disco club. For example, the camera movement in “Crying at the Discotheque” explores the seven different locations, through tracking shots, steady cam shots, and crane shots, making the viewer not only aware of the largeness of space, but also of the absence of people beside the performer. This is reinforced by the point-of-view shots from the performer’s perspective, which forces the audience to share her perspective on the empty dancefloor. Here a connection can be made to the “Sound of Silence (SOS)” photo series by the Dutch photographer Joram Blomkwist, portraying the empty dance floors of eighteen Amsterdam dance clubs during COVID-19 lockdown.4 This emptiness remains out of focus in the Kylie Minogue clip: the one club space in “Magic” is never shown in full, as the view is obstructed through tilted shots, the strobe light effect, and the superimposition of colorful images. Moreover, while the editing of “Crying at the Discotheque” is relatively slow, thus inviting the viewer to explore the club’s emptiness, the rapid editing of “Magic” has a disorienting effect, again obstructing a clear view of the space.

Throughout the audiovisual essay, I have used the opening bars of “Crying at the Discotheque” (the melody of “Spacer”) as a soundtrack, but I have distorted them through reverberation to mimic the muffled sound of an empty space; I also have looped them to echo the repetition characteristic of the retro-disco sound. By disconnecting both music videos from their original soundtracks, I place a stronger emphasis on their visual techniques, which is where they differ most radically.

With these two music videos, director Sophie Muller presents two quite different retro-disco perspectives on club culture during COVID-19. The dance floor of “Magic” is a colorful, throbbing, and lively space, providing a much-needed escapism, while the dance floors of “Crying at the Discotheque” are cold and dead spaces, a clear reminder of what was lost during the COVID-19 epidemic.5 However, one should keep in mind that this is predominantly a visual difference (even enhanced by my manipulation of the soundtrack). Both songs also work as retro disco in the sense that they provide a musical escape from COVID-19, yet without forgetting the dire situation that we needed an escape from. While the “Magic” music video enhances the escapist dimension, “Crying at the Discotheque” reminds us of the reality it allows us to escape from; together, they showcase the two sides—one melancholy, one hedonistic—that are constitutive of the continued cultural force of retro disco.

Notes

- 1 Alexis Petridis, “Pop in 2020: an escape into disco, folklore and nostalgia,” The Guardian (17 December 2020): https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/dec/17/pop-in-2020-an-escape-into-disco-folklore-and-nostalgia

- 2 Emily Caston, “Interview: Sophie Muller,” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 19 (2020): 211–218, https://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue19/HTML/DossierMuller.html

- 3 Carol Vernallis, Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013, 263.

- 4 Joram Blomkwist, “Sound of Silence,” 2020: https://www.blomkwist.com/portfolio/sound-of-silence/

- 5 This observation is informed by a discussion with Maria Pramaggiore about a previous draft version of this audiovisual essay.

d

clustered | unclusteredSecond reflective gesture towards Kanye West’s Runaway, 2010.

Rana El Nemr

I bad food - ghosted

with their binocular eyes they see. they see through people and they foresee. they see too much, it piles, it fills them. they’re sick, they throw up, they no more see. they grow numb. what are they eating when they’re numb? they feed off pain they cause each other they eat the pain, they grow number. their hunger grows their growth is hunger

II ultraviolet - sentient

all air dries out. the skins are fluffing minds leave the bodies. organs are numbing. some lovers meet, when lying in solarium units across the globe.